Director's Cuts That Surpass the Original Theatrical Releases

Simon Thompson examines the ten best director’s cuts that enhance the original theatrical releases…

Director’s cuts are indeed a curious phenomenon. Some significantly elevate or address the original film's strengths and weaknesses, while others tend to dilute a perfectly good film (ahem… Apocalypse Now Redux… ahem) and turn what is fundamentally a collection of deleted scenes into an overhyped experience.

Nevertheless, the ten films featured in this list are prime examples of director’s cuts that are superior to their theatrical counterparts and are often regarded by both fans and critics as the definitive versions of these films…

**Brazil (1985)**

Terry Gilliam stands out as one of American cinema’s great renegades; an insightful and uncompromising filmmaker who has continuously battled studio executives and financiers to present his artistic visions as intended. A notable instance of this struggle occurred during the production of his darkly comedic Orwellian sci-fi film Brazil, which faced ongoing interference from Universal. While the film is a bleak satire on bureaucracy and authoritarianism, featuring a tonally consistent and tragic ending (an homage to 1984), Universal executive Sid Sheinberg clandestinely created a 94-minute cut from the original 142-minute version with a added happy ending, hoping to increase its commercial appeal. This version has since been dubbed the “Love Conquers All” cut by fans, earning a reputation as a gross misrepresentation of Gilliam's artistic intent. Following a contentious back-and-forth with Sheinberg, Gilliam produced a 132-minute cut that was a compromise for the American market. However, the authentic version remains the 142-minute director’s cut, where Gilliam’s nightmarish Kafkaesque vision is fully realized in all its intended grotesqueness.

**Blade Runner (1982)**

Blade Runner is a film that has undergone more transformations than David Bowie. Renowned as one of the most significant science fiction movies ever, it masterfully combines Ridley Scott’s direction, Vangelis’s haunting soundtrack, Douglas Trumbull’s timeless special effects, and a script by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples, along with Syd Mead’s Metal Hurlant-inspired production design. The film's futuristic noir aesthetic was heavily influenced by Moebius and Dan O’Bannon’s 1975 comic The Long Tomorrow, widely regarded as a precursor to the cyberpunk genre.

Set in a dystopian future, Blade Runner presents a dark, cynical noir narrative that felt out of place in a newly commercialized Hollywood wanting to cater to a more family-friendly audience in the aftermath of Star Wars. Consequently, the producers at The Ladd Company mandated a re-cut that included a contrived happy ending, used stock footage from The Shining, included a voiceover that spoon-fed audiences the plot and themes, and eliminated any ambiguity regarding the protagonist Rick Deckard’s nature as a replicant. As a result, the film faltered at the box office, returning only $41 million against its $30 million budget and not receiving favorable reviews from critics.

However, the film's distinctive aesthetic and the lingering cynicism and ambiguity in the original cut garnered Blade Runner a substantial cult following, influencing works such as William Gibson’s The Neuromancer and inspiring a new wave of Japanese sci-fi like Akira, Battle Angel Alita, Ghost in the Shell, and Bubblegum Crisis. In 1992, Scott regained the rights to release his director’s cut, reinstating the original ending and the ambiguity of Deckard's humanity or replicant status. This version was well-received during a test screening and subsequently released on VHS to critical acclaim and renewed appreciation.

Thanks to the initial director’s cut release in the early '90s and the subsequent special edition DVD release of the final cut in 2007, Blade Runner is now rightfully hailed as a pivotal work in the science fiction genre, even earning preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, thanks to Scott's decision to release the director's cut.

**Once Upon a Time In America (1984)**

Sergio Leone's final masterpiece, the sprawling crime epic Once Upon a Time in America, is a raw yet emotionally rewarding film, and as this is my all-time favorite movie across any genre, I may be somewhat biased. This gangster saga, akin to The Godfather (a film Leone turned down during the lengthy pre-production before making Once Upon a Time in America), chronicles the lives of two gangsters during the Prohibition era, portrayed by Robert De Niro and James Woods, traversing a timeline of over thirty years, with De Niro's character returning to New York City in the 1960s to confront the remnants of his past. Throughout this journey, he is haunted by vivid flashbacks of his impoverished childhood and his violent adult life.

Initially running six hours during its Cannes Film Festival appearance in 1984, European distributors negotiated with Leone to produce a four-hour version, which was well

Other articles

Hot Toys has revealed the sixth scale figure of the Cherry Blossom Stormtrooper at Star Wars Celebration Japan.

With only two weeks remaining until the Star Wars Celebration kicks off in Japan, Hot Toys has revealed the limited edition commemorative sixth scale Stormtrooper (Cherry Blossom Version) action figure, coinciding with the convention. Take a look at the promotional images here… SEE ALSO: Star Wars Darth Maul (Concept Art) sixth scale […]

Hot Toys has revealed the sixth scale figure of the Cherry Blossom Stormtrooper at Star Wars Celebration Japan.

With only two weeks remaining until the Star Wars Celebration kicks off in Japan, Hot Toys has revealed the limited edition commemorative sixth scale Stormtrooper (Cherry Blossom Version) action figure, coinciding with the convention. Take a look at the promotional images here… SEE ALSO: Star Wars Darth Maul (Concept Art) sixth scale […]

Ranking All 10 Quentin Tarantino Films

Here are all 10 Quentin Tarantino films ranked. And indeed, we mentioned 10, not nine, for reasons that will be clarified.

Ranking All 10 Quentin Tarantino Films

Here are all 10 Quentin Tarantino films ranked. And indeed, we mentioned 10, not nine, for reasons that will be clarified.

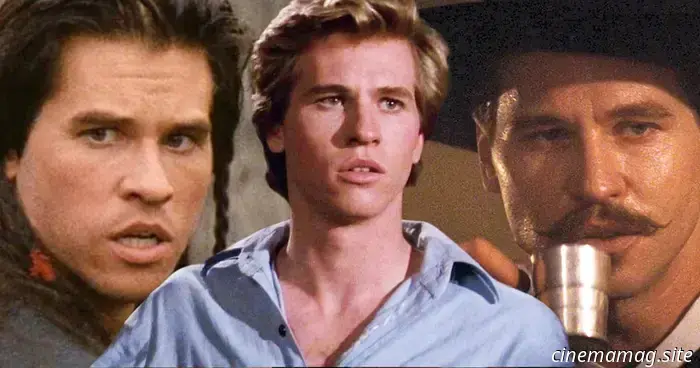

10 Outstanding Performances by Val Kilmer

The late and remarkable Val Kilmer enjoyed a diverse career packed with unforgettable roles and films. Here are ten of his notable performances... Val Kilmer's era as a Hollywood legend was always captivating. Depending on the film set, he could be seen as an enigmatic genius, a joyous addition, or a filmmaker's challenge. What cannot be...

10 Outstanding Performances by Val Kilmer

The late and remarkable Val Kilmer enjoyed a diverse career packed with unforgettable roles and films. Here are ten of his notable performances... Val Kilmer's era as a Hollywood legend was always captivating. Depending on the film set, he could be seen as an enigmatic genius, a joyous addition, or a filmmaker's challenge. What cannot be...

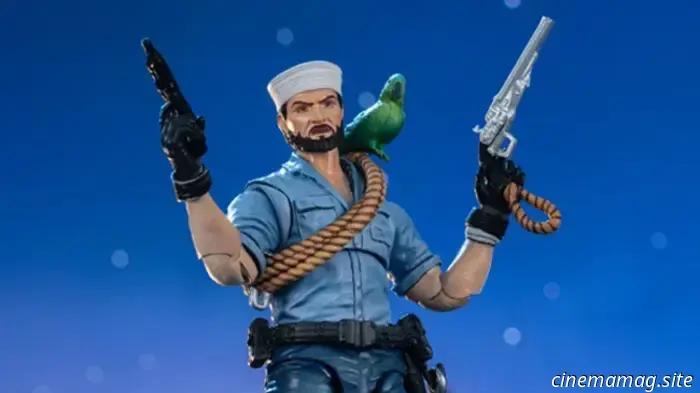

Shipwreck joins Hiya Toys' G.I. Joe Exquisite Mini Series.

Hiya Toys is introducing Shipwreck along with his loyal feathered friend Polly to its 1/18th scale G.I. Joe Exquisite Mini Series. You can view the official promotional images for the new action figure below, with a scheduled release in Q1 2026 at a price of $24.99… SEE ALSO: Recent reveals from Hasbro’s G.I. Joe Classified Series feature Battle […]

Shipwreck joins Hiya Toys' G.I. Joe Exquisite Mini Series.

Hiya Toys is introducing Shipwreck along with his loyal feathered friend Polly to its 1/18th scale G.I. Joe Exquisite Mini Series. You can view the official promotional images for the new action figure below, with a scheduled release in Q1 2026 at a price of $24.99… SEE ALSO: Recent reveals from Hasbro’s G.I. Joe Classified Series feature Battle […]

The story of Everspace 2 advances in May with the release of Wrath of the Ancients.

Rockfish Games has revealed that the highly anticipated expansion for Everspace 2, titled Wrath of the Ancients, will be released on May 12th. This expansion will transport pilots to new star systems where they will face unseen enemies and encounter new challenges. Below is a new trailer that offers a glimpse into the upcoming adventures... […]

The story of Everspace 2 advances in May with the release of Wrath of the Ancients.

Rockfish Games has revealed that the highly anticipated expansion for Everspace 2, titled Wrath of the Ancients, will be released on May 12th. This expansion will transport pilots to new star systems where they will face unseen enemies and encounter new challenges. Below is a new trailer that offers a glimpse into the upcoming adventures... […]

Batman: Dark Patterns #5 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics will be releasing Batman: Dark Patterns #5 this Wednesday, and you can view the official preview of this issue below… Case 02: “The Voice of the Tower”—Part II As tensions escalate between the residents of Scarface Tower and the GCPD, Batman faces off against the tower’s defense mechanisms—an armed gang donning the face […]

Batman: Dark Patterns #5 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics will be releasing Batman: Dark Patterns #5 this Wednesday, and you can view the official preview of this issue below… Case 02: “The Voice of the Tower”—Part II As tensions escalate between the residents of Scarface Tower and the GCPD, Batman faces off against the tower’s defense mechanisms—an armed gang donning the face […]

Director's Cuts That Surpass the Original Theatrical Releases

Simon Thompson examines the ten best director’s cuts that enhance the original theatrical releases. Director’s cuts are quite peculiar. While some significantly improve or correct the original film’s strengths and weaknesses, others often dilute a perfectly fine movie with excessive content (ahem… Apocalypse Now Redux… ahem) [...]