Philippe Lesage discusses Who by Fire, the significance of imperfection, and what television can never take away from cinema.

At the 2019 New Directors/New Films festival, I was profoundly impacted by Philippe Lesage’s emotionally resonant and creatively structured coming-of-age story, Genesis, which I ultimately included in my list of the top 10 films of that year. Now, five years later, the Quebecois director has returned with an impressive follow-up that further showcases his skill for developing well-crafted characters with a broader cast. Who by Fire is a rich, intimate, and psychologically compelling drama that follows two families on a remote retreat as they navigate career aspirations and romantic rivalries.

I had a conversation with Lesage during his visit for the 62nd New York Film Festival premiere of the film last fall, and I'm now sharing our discussion in anticipation of Friday's opening at NYC’s Film at Lincoln Center and next week’s debut at LA’s Laemmle Theatres. We discussed his broadened narrative focus, his filming techniques, the differences between television and film, the music-infused scenes in his work, and his upcoming spiritual follow-up to Genesis.

The Film Stage: Following Berlinale, did you make any modifications to the film? I noticed the runtime is a bit shorter.

Philippe Lesage: It's five minutes shorter than that version.

Ah, so you opted to reduce it slightly?

Yes, it was an exercise I decided to undertake. Initially, I was resistant, mainly due to distribution issues in France. But honestly, a couple of minutes don’t make much difference whether it’s two hours and 25 minutes or two hours and 41 minutes. As I worked on it after watching it numerous times and observing audience reactions in Berlin, I started eliminating scenes that felt a bit long or prolonged. I genuinely enjoy the new version; I think it’s an improvement. I'm not sure if you noticed the difference.

I only saw the new version, actually.

Okay. I simplified some dream sequences, and I really prefer it because in the last dream, it remains unclear whether it’s Aliocha or Jeff who is dreaming. I find that intriguing. Noah [Parker, who plays Jeff] saw the new version last night and preferred it, as did my cinematographer who watched it in Paris. So I feel like I made a wise decision. It’s interesting to modify the film; I feel like a painter adjusting colors in a gallery where the artwork is already displayed.

To start from the beginning, your previous two films primarily focused on adolescence. Although you maintain that theme here, two central characters are adults. What prompted you to delve deeper into adult characters?

I’m not specifically trying to create films about teenagers. My first two films were largely autobiographical, revisiting my own youth. With this film, I thought it would be fascinating to shift the perspective. In my earlier films, adults were almost nonexistent, particularly in Genesis, where they’re barely acknowledged. There are teachers depicted, but I wanted to immerse myself in the experiences of the young people present and depict how they view the adults, even while sharing their stories. That’s the perspective I aimed to convey.

I do critique adulthood and masculinity, symbolically questioning patriarchy as a whole. However, my films don’t start from an idea; it’s about characters and the story I want to tell. Both Genesis and this film have echoes of similar themes. I tend to explore subjects that probe deep feelings. I don’t hold back when it comes to portraying flaws; I find it essential to depict characters with imperfections. It’s much more engaging for me when characters have flaws, even in comedy, as they contribute to the humor. This shift is a transition toward perceiving still-young characters through the lens of adults.

I truly appreciate the cinematography in your films. There’s a controlled warmth that draws viewers in, creating a sense that you’re sharing the cabin experience with the characters. This immersive quality heightens emotional investment, especially when their darker flaws surface. How do you determine the color palette and those beautiful crossfades?

For me, cinema embodies atmosphere and mood. I often reflect on films I loved as a child; despite sometimes violent or challenging narratives, they contained an aspect that made you want to inhabit the world of the film. That’s what I aimed to create: the ambiance of that house, the surrounding woods, the color choices, and the lenses. We used Panavision lenses from the ’70s—classic lenses that may have been used for iconic films. It was essential to capture that texture.

While I can't afford to shoot on film due to budget constraints—this being my largest budget to date, obviously—I typically do 20 takes on average for each shot, making film impractical. However, we sought ways to achieve a texture that wasn’t purely digital. With Balthazar Lab, our cinematographer for this project—who differs from my previous films’ cinematographer, Nicolas Canniccioni—we established the visual language early in the process. Texturing isn’t

Other articles

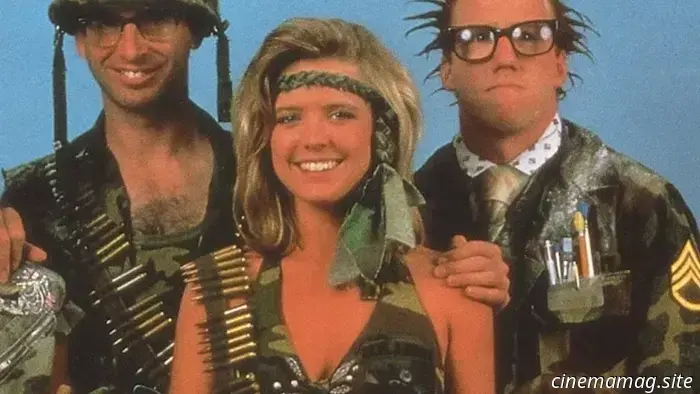

12 Awesome '80s Movies That Only the Cool Kids Remember

We all have memories of blockbuster movies from the '80s, the classics by John Hughes, and the comedy hits that continue to be enjoyed today. However, here are some '80s films that only the cool kids recall.

12 Awesome '80s Movies That Only the Cool Kids Remember

We all have memories of blockbuster movies from the '80s, the classics by John Hughes, and the comedy hits that continue to be enjoyed today. However, here are some '80s films that only the cool kids recall.

SXSW Review: Jay Duplass’ The Baltimorons is a Genuine Nostalgic Return to the Peak of Mumblecore

Jay Duplass makes a notable return to form with his solo-directing debut, The Baltimorons, which serves as a delightful nod to the low-budget indie films he previously directed alongside his brother Mark. Written by and featuring the robust stand-up comedian Michael Strassner, the film, set in Baltimore, chronicles the misadventures of an unexpected romantic pair: Strassner portrays Cliff, a stand-up comedian who is six months

SXSW Review: Jay Duplass’ The Baltimorons is a Genuine Nostalgic Return to the Peak of Mumblecore

Jay Duplass makes a notable return to form with his solo-directing debut, The Baltimorons, which serves as a delightful nod to the low-budget indie films he previously directed alongside his brother Mark. Written by and featuring the robust stand-up comedian Michael Strassner, the film, set in Baltimore, chronicles the misadventures of an unexpected romantic pair: Strassner portrays Cliff, a stand-up comedian who is six months

AMC releases trailer for the adaptation of Liane Moriarty's The Last Anniversary.

AMC has unveiled a poster and trailer for The Last Anniversary, a forthcoming mystery drama series inspired by Liane Moriarty’s New York Times bestseller. Teresa Palmer portrays Sophie, a young woman who inherits a home on the isolated island of Scribbly Gum, where she becomes entangled in an intricate web of family secrets […]

AMC releases trailer for the adaptation of Liane Moriarty's The Last Anniversary.

AMC has unveiled a poster and trailer for The Last Anniversary, a forthcoming mystery drama series inspired by Liane Moriarty’s New York Times bestseller. Teresa Palmer portrays Sophie, a young woman who inherits a home on the isolated island of Scribbly Gum, where she becomes entangled in an intricate web of family secrets […]

-Movie-Review.jpg) The World Will Tremble (2025) - Film Review

The World Will Tremble, 2025. Written and helmed by Lior Geller. Featuring performances by Oliver Jackson-Cohen, Jeremy Neumark Jones, David Kross, Michael Epp, Anton Lesser, George Lenz, Charlie MacGechan, Leonard Proxauf, Tim Bergmann, Adi Kvetner, Aleksandra Kostova, Oliver Möller, and Danny Scheinmann. SYNOPSIS: The astonishing, little-known true account of a group of inmates striving to […]

The World Will Tremble (2025) - Film Review

The World Will Tremble, 2025. Written and helmed by Lior Geller. Featuring performances by Oliver Jackson-Cohen, Jeremy Neumark Jones, David Kross, Michael Epp, Anton Lesser, George Lenz, Charlie MacGechan, Leonard Proxauf, Tim Bergmann, Adi Kvetner, Aleksandra Kostova, Oliver Möller, and Danny Scheinmann. SYNOPSIS: The astonishing, little-known true account of a group of inmates striving to […]

-Movie-Review.jpg) The Electric State (2025) - Film Review

The Electric State, 2025. Directed by Anthony Russo and Joe Russo. Featuring Millie Bobby Brown, Chris Pratt, Woody Harrelson, Ke Huy Quan, Giancarlo Esposito, Stanley Tucci, Anthony Mackie, Brian Cox, Jenny Slate, Woody Norman, Katelin Chesna, Adam Croasdell, Jason Alexander, Cuyle Carvin, Joe Avena, Sebastian Soler, Helen Hunt, Alan Tudyk, Terence Lee, Holly Hunter, Hank […]

The Electric State (2025) - Film Review

The Electric State, 2025. Directed by Anthony Russo and Joe Russo. Featuring Millie Bobby Brown, Chris Pratt, Woody Harrelson, Ke Huy Quan, Giancarlo Esposito, Stanley Tucci, Anthony Mackie, Brian Cox, Jenny Slate, Woody Norman, Katelin Chesna, Adam Croasdell, Jason Alexander, Cuyle Carvin, Joe Avena, Sebastian Soler, Helen Hunt, Alan Tudyk, Terence Lee, Holly Hunter, Hank […]

Leonardo DiCaprio is set to headline Martin Scorsese’s upcoming project, with Apple and Todd Field producing.

Although it has recently been quite challenging to determine what Martin Scorsese will pursue after Killers of the Flower Moon (which premiered at Cannes a couple of years ago), today provides some of the clearest indications of his next project. Unexpectedly, Leonardo DiCaprio will be joining him. According to Publisher's Weekly, Apple Original Films has secured

Leonardo DiCaprio is set to headline Martin Scorsese’s upcoming project, with Apple and Todd Field producing.

Although it has recently been quite challenging to determine what Martin Scorsese will pursue after Killers of the Flower Moon (which premiered at Cannes a couple of years ago), today provides some of the clearest indications of his next project. Unexpectedly, Leonardo DiCaprio will be joining him. According to Publisher's Weekly, Apple Original Films has secured

Philippe Lesage discusses Who by Fire, the significance of imperfection, and what television can never take away from cinema.

During New Directors/New Films in 2019, I was profoundly impacted by Philippe Lesage's emotionally resonant and courageously structured coming-of-age story, Genesis, which I ultimately ranked among my top 10 films of that year. Now, five years later, the Quebecois director is back with a commendable sequel, building on his talent for crafting expertly developed characters with a