Cannes Review: Lynne Ramsay’s Die My Love Resonates Emotionally Despite Jennifer Lawrence’s Powerful Performance

Near the climax of Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here, two assassins––one dressed sharply but near death, the other disheveled yet very much alive––lay together on a kitchen floor, their hands gently touching as Charlene’s “Never Been to Me” floated in from a nearby radio, the lyrics barely escaping the lips of the injured man. This unexpected contrast elevated what was otherwise a clinically well-executed revenge film into something nearing the sublime. Ramsay uses this technique again, though with less impactful results, in her long-anticipated follow-up Die My Love, a visceral, tense film about a woman experiencing a mental breakdown. As usual, Ramsay’s selections for the soundtrack are both engaging and unpredictable, featuring David Bowie’s “Kooks” on a car radio and even the director herself singing an acoustic rendition of “Love Will Tear Us Apart” during the closing credits––a fitting choice for a work centered on toxic love and the actions we take against our loved ones, with little joy in the aftermath of separation.

The film’s most powerful moment of catharsis occurs right at the beginning, where a loud guitar track sets the stage for a heated, strangely edited sex scene between the ill-fated couple. Their names are Grace and Jackson, portrayed by Jennifer Lawrence and Robert Pattinson, who––despite some daring choices in the past––have rarely conveyed this type of physical intensity on screen. This bold energy has been a hallmark of Ramsay’s filmmaking since she debuted with Ratcatcher in 1999, establishing herself as a fresh and vital voice in British cinema. This film remains her only original screenplay; for various reasons, her admirers have had to patiently await each new project. Next week will mark eight years since Here concluded the Cannes competition, and while no film is accountable for audience expectations, it’s hard to watch Die My Love without recalling similar works––most notably Lawrence’s role in Darren Aronofsky’s mother!, as well as Mary Bronstein’s recent film, If I Had Legs I Would Kick You, featuring Rose Byrne.

Die My Love is based on Ariana Harwicz’s debut novel, which is said to have caught the attention of Martin Scorsese before being passed along to Lawrence, who then approached Ramsay for direction. In a tribute to the late, esteemed Gena Rowlands, Lawrence delivers her most compelling performance in years as a woman grappling with her issues under the influence, a young mother whose bipolar behavior is frequently attributed to postpartum depression. Yet, the concerns of those around her often go unheeded. These individuals include her intermittently present husband, who may be having an affair, and her compassionate mother-in-law, portrayed by none other than Sissy Spacek, who is familiar with eccentric screen mothers and seems to enjoy sparring with Lawrence. Their interactions are among the most engaging elements of Die My Love, but their comfortable dynamic only highlights the odd chemistry deficit whenever Lawrence and Pattinson share dialogue.

The screenplay is attributed to Ramsay, Alice Birch (Normal People), and Irish playwright Enda Walsh, a formidable trio that makes the rigid tone and indulgent dream-logic particularly perplexing. While I might classify this as the director’s weakest film, the fact remains that she has never made a poor one, diminishing the weight of that assessment. Regardless, Die My Love holds value––not least for how Lawrence moves through the tall grass, one hand gripping a knife and the other tucked into her jeans, adding a perilous, sexual tension to the screen. This is undoubtedly a Lynne Ramsay film. Let’s hope we don’t wait another eight years for the next one.

Die My Love premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival and will be released by MUBI.

Other articles

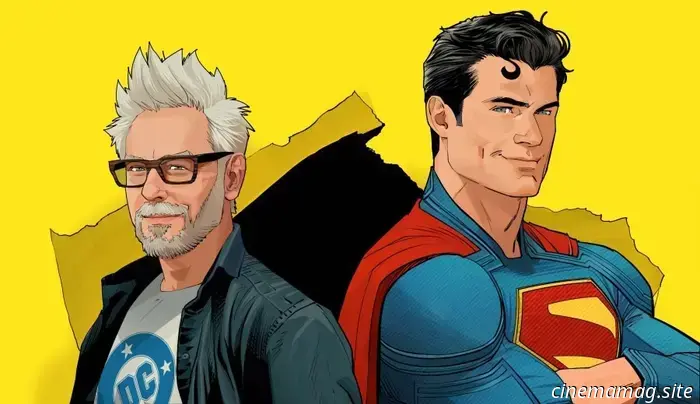

Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 - Comic Book Teaser

DC Comics will be launching Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 this Wednesday, and you can check out a preview of the issue below... “We Are Yesterday” Part Four (of six) The Batman and Superman from the past…in the present?! As Gorilla Grodd's brutal time attack on the Justice League persists, the Dark Knight and Man of […]

Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 - Comic Book Teaser

DC Comics will be launching Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 this Wednesday, and you can check out a preview of the issue below... “We Are Yesterday” Part Four (of six) The Batman and Superman from the past…in the present?! As Gorilla Grodd's brutal time attack on the Justice League persists, the Dark Knight and Man of […]

Cannes Review: Chie Hayakawa’s Renoir Presents a Slowly Unfolding and Rewarding Coming-of-Age Tale

Only three years after receiving a special mention from the Camera d’Or jury for Plan 75, Chie Hayakawa makes her return to Cannes as one of seven filmmakers making their debut in the main competition—an unconventional change of pace for a festival traditionally aligned with established names. In Plan 75, a sharp piece of speculative fiction,

Cannes Review: Chie Hayakawa’s Renoir Presents a Slowly Unfolding and Rewarding Coming-of-Age Tale

Only three years after receiving a special mention from the Camera d’Or jury for Plan 75, Chie Hayakawa makes her return to Cannes as one of seven filmmakers making their debut in the main competition—an unconventional change of pace for a festival traditionally aligned with established names. In Plan 75, a sharp piece of speculative fiction,

Superman Unlimited #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics is set to debut its new ongoing series, Superman Unlimited, this Wednesday. You can view the official preview of the inaugural issue below. The summer of Superman intensifies with this fresh ongoing series that’s making waves in the DC Universe! As an asteroid the size of Metropolis approaches Earth, the […]

Superman Unlimited #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics is set to debut its new ongoing series, Superman Unlimited, this Wednesday. You can view the official preview of the inaugural issue below. The summer of Superman intensifies with this fresh ongoing series that’s making waves in the DC Universe! As an asteroid the size of Metropolis approaches Earth, the […]

Broadway and Bronx are now part of PCS' Gargoyles collectibles series with a quarter-scale statue.

Following the release of its initial Gargoyles figure last month featuring Goliath and Lexington, Premium Collectibles Studio has now presented the quarter scale Broadway and Bronx statue inspired by the beloved 90s Disney animated series. This collectible is currently up for pre-order at an early bird price of $1,187.50—so be sure to start saving! Take a look at the […]

Broadway and Bronx are now part of PCS' Gargoyles collectibles series with a quarter-scale statue.

Following the release of its initial Gargoyles figure last month featuring Goliath and Lexington, Premium Collectibles Studio has now presented the quarter scale Broadway and Bronx statue inspired by the beloved 90s Disney animated series. This collectible is currently up for pre-order at an early bird price of $1,187.50—so be sure to start saving! Take a look at the […]

Star Wars: The High Republic – Fear of the Jedi #4 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Star Wars: The High Republic – Fear of the Jedi #4 is set to release this Wednesday, and you can view the official preview of the issue below, brought to you by Marvel Comics… KEEVE TRENNIS and her group of exhausted Jedi are confronted with their greatest challenge…and their deepest fear. The NAMELESS attack like you’ve never witnessed before […]

Star Wars: The High Republic – Fear of the Jedi #4 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Star Wars: The High Republic – Fear of the Jedi #4 is set to release this Wednesday, and you can view the official preview of the issue below, brought to you by Marvel Comics… KEEVE TRENNIS and her group of exhausted Jedi are confronted with their greatest challenge…and their deepest fear. The NAMELESS attack like you’ve never witnessed before […]

How Freddy MacDonald Made His Feature Debut at 24 with Sew Torn

Some fathers show their sons how to catch a ball or tie a tie, and we are confident that Sew Torn director Freddy MacDonald learned those skills from his dad as well. However, he also

How Freddy MacDonald Made His Feature Debut at 24 with Sew Torn

Some fathers show their sons how to catch a ball or tie a tie, and we are confident that Sew Torn director Freddy MacDonald learned those skills from his dad as well. However, he also

Cannes Review: Lynne Ramsay’s Die My Love Resonates Emotionally Despite Jennifer Lawrence’s Powerful Performance

Just before the climax of Lynne Ramsay's You Were Never Really Here, two assassins—one elegantly attired but fading, the other disheveled yet very much alive—found themselves on the kitchen floor, their hands softly brushing against each other as Charlene's "Never Been to Me" played softly from a nearby radio, the words barely escaping the lips of the injured man. That striking contrast