Cannes Review: Chie Hayakawa’s Renoir Presents a Slowly Unfolding and Rewarding Coming-of-Age Tale

Just three years after receiving a special mention from the Camera d’Or jury for Plan 75, Chie Hayakawa returns to Cannes as one of seven filmmakers making their debut in the main competition—an unusual breath of fresh air from a festival that often favors established names. In Plan 75, an incisive piece of speculative fiction, Hayakawa envisioned a near-future Japan addressing its aging population crisis through a voluntary euthanasia program. In her second feature, Renoir, she tackles similar themes, focusing on family, death, and generational tensions, while reflecting on her own past rather than looking to the future.

With its everyday details (captured in beautiful, muted tones by DP Hideho Urata), the presence of veteran actor Lily Franky, and a leisurely pace, Renoir tells a coming-of-age story that fans of Hirokazu Kore-eda might find familiar, although it lacks his characteristic sentimentality. Hayakawa’s perspective is both consistent and watchful, balancing the joys and challenges of a pivotal summer. The narrative centers on Fuki (Yui Suzuki), an introverted 11-year-old striving to navigate adolescence. Her father (Franky) is bedridden with cancer, while her mother, Utako (Hikari Ishida), is occupied with work. Frequently left to her own devices, Fuki escapes into her imagination and develops an interest in hypnosis, which she tries out on a woman living above her and a new friend from her language school. Set in 1987, during Japan’s economic bubble, the film reflects some of Hayakawa’s own experiences of losing her father at a similar age.

The outcome is a rich and gradually rewarding bildungsroman—a film that may feel cold to the touch but offers much to contemplate. In a recent interview with Variety, Hayakawa confessed to having written various drafts of the script in her 20s, fearing they might be too dark. This should be viewed with a healthy dose of skepticism: even in lighter moments, Renoir's atmosphere remains tenuous. The film begins with Fuki envisioning her own murder (a gruesome strangulation in her own bed) and funeral for an essay she is reading to her class, which likely sets the tone for what to expect from the film.

Fuki isn’t inclined to speak; instead, Hayakawa has her listen to the adults around her, leaving viewers to wonder whose influence she may ultimately absorb. There’s the compassionate teacher who commends her writing while expressing concern over some of its themes (he even brings her mother in for a meeting about an essay titled “I Want to Be an Orphan”). There’s a charming man (Ayumu Nakajima) who dines with her and Utako, the subject of Fuki’s attempted curse. Most troubling is Kaori (Ryota Bando), a groomer she converses with on a phone-in dating line, who persuades her to meet him in a particularly unsettling scene.

The late-80s backdrop, on the verge of a bubble burst, situates Renoir at a crucial moment in Japanese history; however, Hayakawa’s film delves into internal worlds that can sometimes feel unreachable. While this and a somewhat monotonous tone may distance some viewers, it is fascinating to observe the director gradually unveil these memories.

Renoir had its premiere at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

Other articles

Cannes Review: Richard Linklater Delivers a Masterclass in Cinema with Nouvelle Vague

Filmed in black-and-white using the same Cameflex model that Jean-Luc Godard employed for Breathless—the very film it represents and captures—the Nouvelle Vague is not simply a mimicry of Godard. Rather, it appropriates his style to forge its own unique creation, which is an unusual statement to make about a film that visually resembles

Cannes Review: Richard Linklater Delivers a Masterclass in Cinema with Nouvelle Vague

Filmed in black-and-white using the same Cameflex model that Jean-Luc Godard employed for Breathless—the very film it represents and captures—the Nouvelle Vague is not simply a mimicry of Godard. Rather, it appropriates his style to forge its own unique creation, which is an unusual statement to make about a film that visually resembles

-4K-Ultra-HD-Review.jpg) Starman (1984) - Review in 4K Ultra HD

Starman, 1984. Directed by John Carpenter. Featuring Jeff Bridges, Karen Allen, Charles Martin Smith, and Richard Jaeckel. SYNOPSIS: Previously available exclusively in the Columbia Classics: Volume 4 collection, the 4K Ultra HD edition of John Carpenter’s Starman is now released as an individual Steelbook edition. The set does not include the two discs that contain the single-season TV series, […]

Starman (1984) - Review in 4K Ultra HD

Starman, 1984. Directed by John Carpenter. Featuring Jeff Bridges, Karen Allen, Charles Martin Smith, and Richard Jaeckel. SYNOPSIS: Previously available exclusively in the Columbia Classics: Volume 4 collection, the 4K Ultra HD edition of John Carpenter’s Starman is now released as an individual Steelbook edition. The set does not include the two discs that contain the single-season TV series, […]

Cannes Review: Ari Aster’s Eddington is an ambitious period film set in the 2020s that succeeds in moments.

In Eddington, Ari Aster’s newest descent into despair, the plan to construct a data center in remote New Mexico triggers a long-awaited psychological collapse. The central figure is Sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), who deals with a troubling array of issues, including an overly engaged mother-in-law (Deirdre O'Connell), and a seemingly indifferent, catatonic spouse (Emma Stone).

Cannes Review: Ari Aster’s Eddington is an ambitious period film set in the 2020s that succeeds in moments.

In Eddington, Ari Aster’s newest descent into despair, the plan to construct a data center in remote New Mexico triggers a long-awaited psychological collapse. The central figure is Sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), who deals with a troubling array of issues, including an overly engaged mother-in-law (Deirdre O'Connell), and a seemingly indifferent, catatonic spouse (Emma Stone).

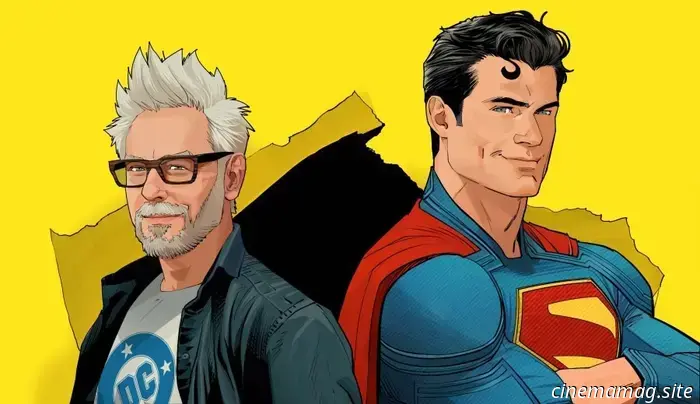

Superman Unlimited #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics is set to debut its new ongoing series, Superman Unlimited, this Wednesday. You can view the official preview of the inaugural issue below. The summer of Superman intensifies with this fresh ongoing series that’s making waves in the DC Universe! As an asteroid the size of Metropolis approaches Earth, the […]

Superman Unlimited #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics is set to debut its new ongoing series, Superman Unlimited, this Wednesday. You can view the official preview of the inaugural issue below. The summer of Superman intensifies with this fresh ongoing series that’s making waves in the DC Universe! As an asteroid the size of Metropolis approaches Earth, the […]

Cannes Review: Lav Diaz's Magellan is a Captivating, Clear Examination of the Atrocities of Colonization.

Ferdinand Magellan has not typically been seen as a significant figure in history, and Lav Diaz’s unexpectedly traditional––though still captivatingly slow––biopic employs a genre framework to further disavow his legacy. Originating from a long-planned project centered on Magellan’s wife Beatriz, the film now serves as an unconventional companion of sorts: it is a piece that you could never confuse for

Cannes Review: Lav Diaz's Magellan is a Captivating, Clear Examination of the Atrocities of Colonization.

Ferdinand Magellan has not typically been seen as a significant figure in history, and Lav Diaz’s unexpectedly traditional––though still captivatingly slow––biopic employs a genre framework to further disavow his legacy. Originating from a long-planned project centered on Magellan’s wife Beatriz, the film now serves as an unconventional companion of sorts: it is a piece that you could never confuse for

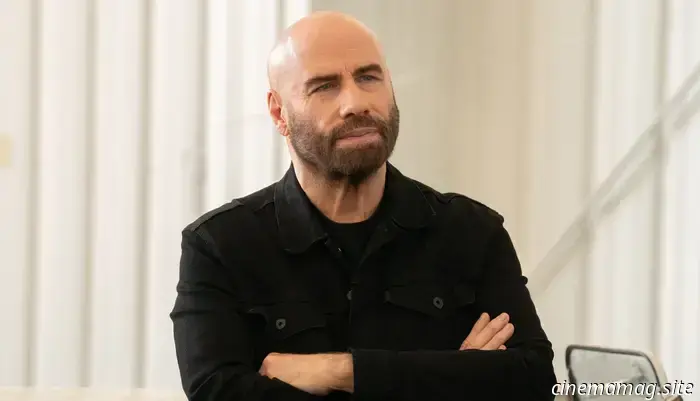

John Travolta is set to confront rogue orcas in Renny Harlin's Black Tides.

John Travolta is preparing to face a battle for survival against a group of hungry orcas. According to Deadline, the actor is collaborating with Renny Harlin, known for directing Die Hard 2 and Cliffhanger, for the project titled Black Tides. The survival thriller has been penned by Chris Sparling (Buried) and Ángel Agudo (Apocalypse Z), and will […]

John Travolta is set to confront rogue orcas in Renny Harlin's Black Tides.

John Travolta is preparing to face a battle for survival against a group of hungry orcas. According to Deadline, the actor is collaborating with Renny Harlin, known for directing Die Hard 2 and Cliffhanger, for the project titled Black Tides. The survival thriller has been penned by Chris Sparling (Buried) and Ángel Agudo (Apocalypse Z), and will […]

Cannes Review: Chie Hayakawa’s Renoir Presents a Slowly Unfolding and Rewarding Coming-of-Age Tale

Only three years after receiving a special mention from the Camera d’Or jury for Plan 75, Chie Hayakawa makes her return to Cannes as one of seven filmmakers making their debut in the main competition—an unconventional change of pace for a festival traditionally aligned with established names. In Plan 75, a sharp piece of speculative fiction,