J. Hoberman discusses New York in the 1960s, focusing on the protests, the alternative press, and those deemed as outcasts.

In Margaret O’Brien's reflection on coming of age in her beloved city within *Meet Me in St. Louis*, she considers herself fortunate. Her formative years as an undergraduate coincided with J. Hoberman’s role as chief film critic for the *Village Voice*. She describes his perspective as one that views films as both artifacts and reflections of intertwining artistic, social, and political contexts, which profoundly shaped her, as it has for other critics striving to navigate the relationship between art and the world. A clever observer once noted that Hoberman’s end-of-year top ten list was a rare glimpse into the films he genuinely appreciated, and O’Brien believes there is no better education than the encouragement found in his work to bypass aesthetic hierarchies in favor of interconnections and personal interpretations.

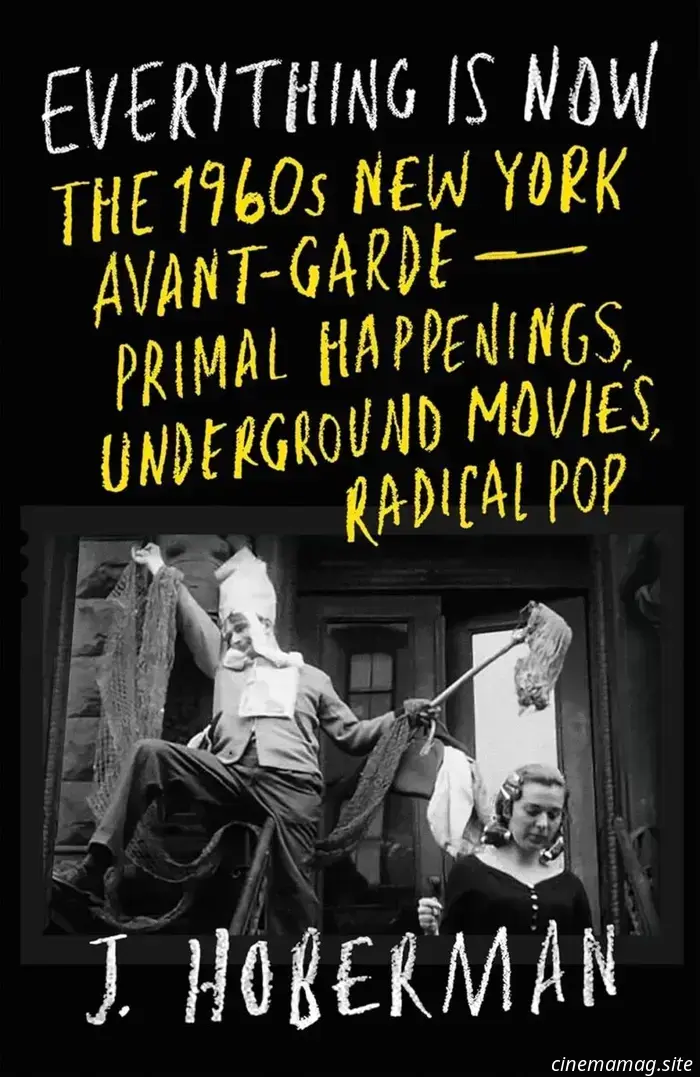

Hoberman's latest book, *Everything Is Now*, chronicles a period in New York City when artistic networks were particularly vibrant. He immerses readers in the underground art movements of the 1960s, including Jack Smith's campy films, boundary-pushing plays by the Living Theatre and the Performance Group, Ornette Coleman's free jazz, Yayoi Kusama's nude happenings, Pop and Op art, agit-folk music, psychedelic light shows, and more. The book's structure divides it into "Subculture" and "Counterculture," moving chronologically through the decade and illustrating how the oppositional aesthetics of alternative art movements influenced the tactics of political activism, especially as the Vietnam War intensified and youth culture solidified its presence. Local radical performances evolved into national spectacles through the burgeoning mass media. Although largely unspoken, O’Brien finds it evident that avant-garde "superstars" were pioneers of techniques that would later facilitate the emergence of Reagan's political era—a narrative Hoberman explores in depth in his *Found Illusions* trilogy, which includes *The Dream Life*, *An Army of Phantoms*, and *Make My Day*, documenting the intertwining of the Cold War and American myths as expressed in cinema.

Throughout *Everything Is Now*, lower Manhattan is depicted as a thriving community where art, both exhilarating and exhausting yet always at the forefront of creativity, unfolds live and garners attention through alternative publications that report on and discuss what’s happening weekly. The book serves as an homage to the closer-knit (and more affordable) city that Hoberman, like all New Yorkers of any generation, once cherished. The young author appears throughout as an eager reader of the *Voice* and an uninvited guest at Dylan concerts, but the narrative gives voice to outliers, supporters, and legends of the scene, both artists and those who chronicled them. Figures come and go, past writers fade while new names emerge, trends rise and fall; yet the city endures. The book is currently available; a film series showcasing films mentioned within it—including experimental masterpieces, rare performance documentation, and a simultaneous screening of Alejandro Jodorowsky's *El Topo* paired with Robert Kramer’s *Ice*—is scheduled to run from June 20 to 24 at Anthology Film Archives, one of the last remnants of the world Hoberman captures in *Everything Is Now*.

Earlier this week, I spoke with Hoberman.

**The Film Stage:** Let’s start with the topic of political theater and public demonstrations. Just yesterday, a mayoral candidate was physically confronted and arrested by federal agents while assisting New Yorkers exiting immigration court. Footage of the event was rapidly shared on social media and featured on the *Times* website; a spontaneous rally emerged downtown.

**J. Hoberman:** I was present.

This incident could definitely merit inclusion in *Everything Is Now 2025*. What similarities do you perceive between the events you write about in the book and your observations—or participation—today?

It was groundbreaking when Abbie Hoffman—and perhaps another Yippie—proclaimed, “the whole world is watching” after Chicago ’68. While the world wasn't truly watching in real-time, the realization that a street demonstration could gain global attention was profound. The slogan itself was impactful as well. I can't say if today's occurrences carry the same weight. The rise of pop-up rallies can certainly be attributed to the Internet, facilitating near-instantaneous gatherings to which numerous political figures arrived. That surprised me most—also, it was a visually appealing crowd.

However, there’s a paradox, as things seem even more fragmented now. You can rally your—what Vonnegut termed in *Cat's Cradle*—your karass, your granfalloon—but does it reach beyond that?

My discussion in the book regarding happenings—the term used at the time—illustrates a new form of performance that transitioned from galleries and studios to the streets. Abbie Hoffman grasped how to leverage these seemingly absurd happenings to make political statements. I’m uncertain whether such impact is possible today; perhaps I’m mistaken in my assessment.

Are you intrigued by Instagram, TikTok,

Other articles

12 Greatest Superhero Films Prior to the MCU

12 Greatest Superhero Films Prior to the MCU

The parody of The Exorcist, titled Repossessed, is set to be released on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber.

Kino Lorber has revealed that Bob Logan’s cult classic parody of The Exorcist, Repossessed, released in 1990, will be available on Blu-ray starting August 19th. Take a look at the cover art and further details here… Are you prepared for an entertainingly frightful experience? Linda Blair will have you laughing and screaming when she’s Repossessed! Blair plays the lead role in this hilariously spooky parody […]

The parody of The Exorcist, titled Repossessed, is set to be released on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber.

Kino Lorber has revealed that Bob Logan’s cult classic parody of The Exorcist, Repossessed, released in 1990, will be available on Blu-ray starting August 19th. Take a look at the cover art and further details here… Are you prepared for an entertainingly frightful experience? Linda Blair will have you laughing and screaming when she’s Repossessed! Blair plays the lead role in this hilariously spooky parody […]

Giant-Size Age of Apocalypse #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Ms. Marvel's exploration of X-Men history progresses this Wednesday with Giant-Size Age of Apocalypse #1. You can view the official preview below, provided by Marvel Comics. Kamala Khan has triumphed in her battle against Legion, but now both find themselves trapped in the bleakest future of all: [...]

Giant-Size Age of Apocalypse #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Ms. Marvel's exploration of X-Men history progresses this Wednesday with Giant-Size Age of Apocalypse #1. You can view the official preview below, provided by Marvel Comics. Kamala Khan has triumphed in her battle against Legion, but now both find themselves trapped in the bleakest future of all: [...]

8 Outstanding Recent Movies You Definitely Should Watch

It's time to highlight some recent movies that should be on your watchlist... You brought the kids to cheer for "Chicken Jockey" and check out the first screening at your nearby multiplex. Perhaps you also took them to watch Lilo & Stitch. Just a week after its release and with positive buzz, you decided to go to [...]

8 Outstanding Recent Movies You Definitely Should Watch

It's time to highlight some recent movies that should be on your watchlist... You brought the kids to cheer for "Chicken Jockey" and check out the first screening at your nearby multiplex. Perhaps you also took them to watch Lilo & Stitch. Just a week after its release and with positive buzz, you decided to go to [...]

Dan Trachtenberg, the director of Prey and Badlands, hints at another Predator film.

Dan Trachtenberg is aware that there's a strong desire for more Predator content, particularly if he is the one directing, and it seems we might just get it. The director has recently confirmed that he is developing a fourth film after the success of Prey and his two subsequent projects. Trachtenberg humorously mentioned that he “kind of rushed” the animated film Predator: Killer of Killers and the […]

Dan Trachtenberg, the director of Prey and Badlands, hints at another Predator film.

Dan Trachtenberg is aware that there's a strong desire for more Predator content, particularly if he is the one directing, and it seems we might just get it. The director has recently confirmed that he is developing a fourth film after the success of Prey and his two subsequent projects. Trachtenberg humorously mentioned that he “kind of rushed” the animated film Predator: Killer of Killers and the […]

DC x Sonic The Hedgehog #4 - Comic Book Teaser

DC x Sonic The Hedgehog #4 is set to hit comic book stores this Wednesday, and we have the official preview for you below; take a look... The world of Sonic the Hedgehog is in danger! Fortunately, the Justice League has arrived to come to the rescue! Even while being totally out of their comfort zone, Earth’s […]

DC x Sonic The Hedgehog #4 - Comic Book Teaser

DC x Sonic The Hedgehog #4 is set to hit comic book stores this Wednesday, and we have the official preview for you below; take a look... The world of Sonic the Hedgehog is in danger! Fortunately, the Justice League has arrived to come to the rescue! Even while being totally out of their comfort zone, Earth’s […]

J. Hoberman discusses New York in the 1960s, focusing on the protests, the alternative press, and those deemed as outcasts.

To rephrase Margaret O’Brien in Meet Me in St. Louis: How fortunate I was to grow up in my beloved city! For one reason, my formative college years coincided with J. Hoberman’s time as the main film critic for the Village Voice, and I would describe his method as viewing films as artifacts or perhaps indicators.