Venice Review: Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt Presents a Retrogressive, Uninspired Perspective on the Post-MeToo Period

“It’s a fucking minefield, Alma,” warns the Dean of Humanities at Yale to Julia Roberts' Dr. Imhoff. Just a few days have passed since her colleague, Hank (Andrew Garfield), has "crossed the line" with one of her students, Maggie (Ayo Edebiri), and Alma, a philosophy professor on the cusp of tenure, is grappling with the aftermath of a sexual assault that compels her to rethink her loyalties. (Maggie is her favorite student; Hank is her best friend and, not insignificantly, a former lover.) Several characters in Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt will share their perspectives on our post-MeToo culture—a “shallow cultural climate” (according to Hank) dominated by “the abusive patriarchal agenda” (as Maggie puts it). Yet, of all the attempts to encapsulate our current cultural moment, the Dean’s observation most accurately reflects the film’s clumsy treatment of the central horrific incident. After the Hunt seeks to address what is often referred to as cancel culture, but grappling with such a significant topic doesn’t equate to genuinely confronting it; if there is anything authentically uncomfortable about Guadagnino’s film, it lies not in controversial issues but in the reactionary manner it mishandles them.

This marks the first feature script from actress Nora Garrett, who stated in a recent Vanity Fair interview that she did not base her screenplay on any specific case—even disregarding the misleading title card implying “it happened at Yale.” Garrett noted: “We were lacking a sense of gray area, and we also needed to understand how power obscures reality, how those in power often face no consequences, while those without it are left vulnerable to them.” While this observation is significant, it lingered in my mind throughout the film due to a pressing question it raises: where is the gray?

Driven by the violence Maggie suffers at the hands of one of her educators, After the Hunt fundamentally centers on Alma. This focus is evident in the visual hierarchies created by Malik Hassan Sayeed’s shallow-focus cinematography, where the camera often isolates Alma’s face over others, including Maggie’s. In a crucial moment between them, as Maggie declares her intention to file charges against Hank, it is Roberts’ distressed expression that the camera lingers on, blurring Maggie’s image in the foreground. However, it is in the script that Alma’s perspective takes precedence in a way that feels particularly unsettling. By anchoring the narrative to her journey, Garrett reduces those around her to mere symbols confined within their own echo chambers.

Alma resides with her husband Frederik (Michael Stuhlbarg) in an opulent apartment where she entertains with long, boozy discussions open to both faculty and students. In the prologue, we witness her flirting with Hank while basking in Maggie’s admiration. Frederik’s feelings of inadequacy about his wife’s energetic endeavors to charm her insulated group of admirers might explain his tendency to belittle Maggie during a later dinner scene, where she finally shares details about her thesis (arguably the sole instance in After the Hunt where Edebiri’s character is recognized outside her trauma). Yet, Frederik’s treatment of Maggie represents one of Guadagnino’s least imaginative moments. He may not be an “asshole,” as Alma accuses him of being when he interrupts her conversation with Maggie by blasting classical music, but he is revealed as something even bleaker: a caricature.

He is not the only one. It takes Chloë Sevigny more than an hour to deliver her first line; when she eventually does, her character—Kim, a therapist at Yale and one of Dr. Imhoff’s closest friends—is chatting with Alma in a bar filled with students. She complains about how public restrooms have become dirtier since they became gender-neutral, then shifts her drunken rant to our “insane times” and Maggie’s situation: “What happened to the days of just burying everything and developing a crippling dependency in your thirties like the rest of us?” Alma departs, but Kim remains, shocked that the bar is playing a song by the Smiths, which she presumably loves, alongside a poster of Clint Eastwood with a gun that is the only decoration in her otherwise bland office.

The issue isn’t Kim’s nostalgic feelings, nor are her rants against these privileged kids she feels disconnected from problematic. The problem lies in how these details and jokes reflect Frederik’s outbursts: they end up mocking these characters and their viewpoints while diminishing Maggie’s trauma. This isn’t merely an oversight, but rather a reflection of the film’s approach. To emphasize its themes, After the Hunt must categorize Alma and her peers as members of an older generation significantly disconnected from Maggie’s, reducing them to opposing factions. This is a valid point, yet the film’s tendency to portray everyone—from boomers to millennials to Gen Z—as spokesperson

Other articles

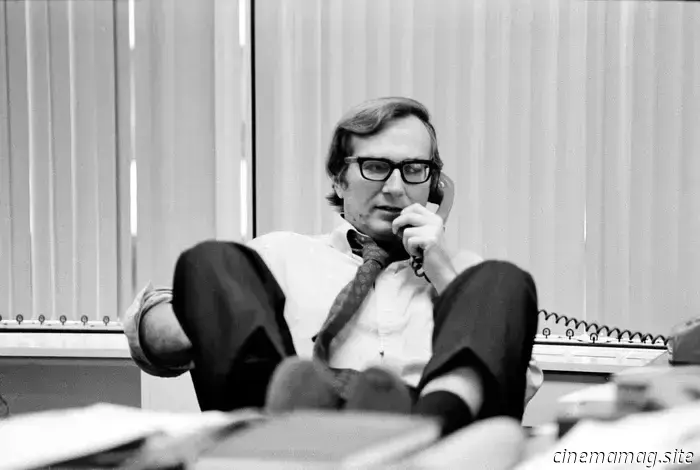

Venice Review: Cover-Up Is the Most Significant American Documentary of the Year

Three years after Venice honored Laura Poitras's documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, which features artist and activist Nan Goldin, with the Golden Lion, another film by the Academy Award-winning director is being showcased at the Lido. Cover-Up, co-directed by Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, focuses on the esteemed journalist Seymour (Sy) Hersh and his extensive career that has spanned from

Venice Review: Cover-Up Is the Most Significant American Documentary of the Year

Three years after Venice honored Laura Poitras's documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, which features artist and activist Nan Goldin, with the Golden Lion, another film by the Academy Award-winning director is being showcased at the Lido. Cover-Up, co-directed by Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, focuses on the esteemed journalist Seymour (Sy) Hersh and his extensive career that has spanned from

Star Wars: Han Solo – Hunt for the Falcon #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Marvel Comics is set to launch its new series Star Wars: Han Solo – Hunt for the Falcon next week, and you can check out an early preview of the first issue with the official sneak peek below... IN THE PERIOD PRIOR TO THE FORCE AWAKENS, WHERE HAS THE MILLENNIUM FALCON GONE?! With a growing discontent for a quiet life, [...]

Star Wars: Han Solo – Hunt for the Falcon #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Marvel Comics is set to launch its new series Star Wars: Han Solo – Hunt for the Falcon next week, and you can check out an early preview of the first issue with the official sneak peek below... IN THE PERIOD PRIOR TO THE FORCE AWAKENS, WHERE HAS THE MILLENNIUM FALCON GONE?! With a growing discontent for a quiet life, [...]

Justice League vs. Godzilla vs. Kong 2 #4 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics will release Justice League vs. Godzilla vs. Kong 2 #4 on Wednesday, and below, we have an official preview of the issue… It's the showdown fans have been anticipating: Godzilla takes on Superman! With the Man of Steel not operating at peak strength, can he withstand the power of the King […]

Justice League vs. Godzilla vs. Kong 2 #4 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics will release Justice League vs. Godzilla vs. Kong 2 #4 on Wednesday, and below, we have an official preview of the issue… It's the showdown fans have been anticipating: Godzilla takes on Superman! With the Man of Steel not operating at peak strength, can he withstand the power of the King […]

Star Trek: Voyager - Homecoming #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

IDW is commemorating the 30th anniversary of Star Trek: Voyager by introducing a new limited series titled Star Trek: Voyager – Homecoming, which presents one final untold adventure for Captain Kathryn Janeway and the USS Voyager crew. Check out the official preview below for an exclusive look at the first issue… Captain Kathryn Janeway […]

Star Trek: Voyager - Homecoming #1 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

IDW is commemorating the 30th anniversary of Star Trek: Voyager by introducing a new limited series titled Star Trek: Voyager – Homecoming, which presents one final untold adventure for Captain Kathryn Janeway and the USS Voyager crew. Check out the official preview below for an exclusive look at the first issue… Captain Kathryn Janeway […]

Venice Review: Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt Presents a Retrogressive, Uninspired Perspective on the Post-MeToo Period

“It’s an absolute minefield, Alma,” advises the Dean of Humanities at Yale to Julia Roberts’ Dr. Imhoff. Just a few days have gone by since her colleague, Hank (Andrew Garfield), has “crossed the line” with one of her students, Maggie (Ayo Edebiri), and Alma, a philosophy professor nearing tenure, is attempting to maneuver through the