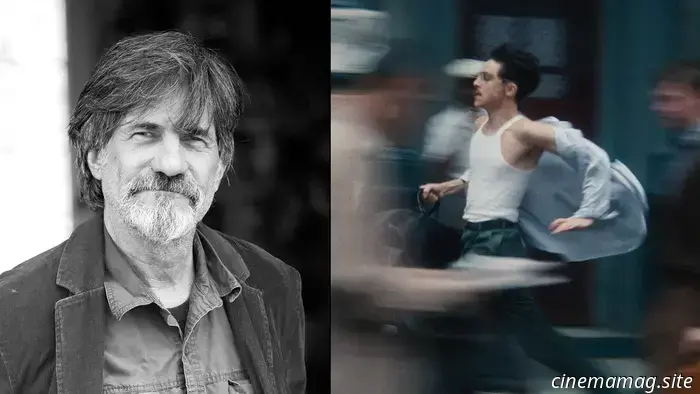

Jack Fisk on Crafting an Authentic 1950s New York for Marty Supreme and Josh Safdie’s Drive

Over the last fifty years, production designer Jack Fisk has worked alongside a remarkable array of writer-directors, including Terrence Malick, David Lynch, Brian De Palma, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Alejandro González Iñárritu. It was somewhat surprising that he hadn’t collaborated with Martin Scorsese until a few years ago, when he recreated 1920s Fairfax, Oklahoma for Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. (Anderson had previously recommended Fisk to Scorsese after his outstanding work on The Master and There Will Be Blood.) Fisk is known for his commitment to authenticity in every detail, believing that this approach benefits the actors by allowing them to delve deeper into their roles and enhances the audience's immersion in the film’s world. For Malick’s The New World, Fisk and his team built the 17th-century Jamestown fort without modern technology, instructing his crew to use a stick instead of tape measures.

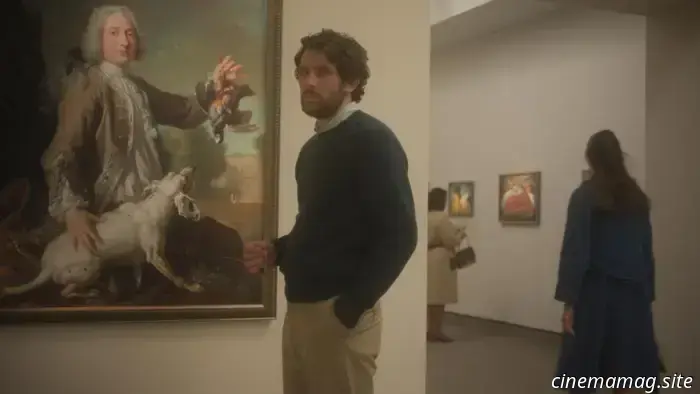

In Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme, Fisk applies his renowned attention to detail and extensive research to create a vision of 1950s New York City. True to Safdie's style, the story follows ping pong champion Marty Mauser (Timothée Chalamet) on a whirlwind journey across the city—from the famous Orchard Street on the Lower East Side to the quieter Upper Manhattan and even to rural New Jersey. His travels are international, starting in London and concluding in Tokyo. I spoke with Fisk about how he visually differentiated the various locations, his research process that includes examining personal journals and street photography from the era, and his aversion to overly pristine period pieces.

The Film Stage: You’ve collaborated with many familiar directors over the years, but your last three films have featured new filmmakers. What do you look for when meeting a director to potentially work with on a project?

Jack Fisk: I seek out passion. Most of the directors I collaborate with are also writers, meaning they’ve been deeply involved with their stories for a long time. I first heard from Josh Safdie while I was in Oklahoma working with Martin Scorsese on Killers [of the Flower Moon], and he was already very enthusiastic about it. Three years later, he called me back, and said, “I got the money. Let’s go.” He has a deep love for New York; he cherishes his life here and is fully invested in sharing Marty’s story. Just like Josh's passion for filmmaking, Marty has a similar drive for table tennis—he aspires to be great. We all nurture those ambitions in our youth. Some achieve them while others don’t, and it may come off as selfish or even obnoxious to outsiders, but at the same time, you can’t help but admire that dedication. You think, “Oh, I wish I had done that,” or “I felt that.” There’s a shared understanding. Josh mirrors Marty in his filmmaking; he’s finding success and winning tournaments, which contributes to his enthusiasm for Marty’s story.

As I grow older, it’s becoming more challenging to find veteran directors who still make films annually, so I’m excited to discover young filmmakers who remind me of them. The ’70s, when I began my career, was a vibrant time in cinema; the studios were faltering, and after the success of Easy Rider, young directors were granted opportunities. They had a voice and began crafting intriguing films, which ultimately led to my meeting with Terrence Malick and Brian De Palma. David Lynch and I attended high school together in Virginia before we moved to L.A. in a U-Haul truck. My journey into production design feels like a charmed path. Even as a child, I loved creating, building forts and rearranging my room weekly. It felt like a natural progression. I didn’t consider filmmaking until I arrived in Los Angeles, but once I started, I couldn’t imagine a job I’d enjoy more. Driving to work in the morning, there’s nowhere else I’d rather be headed.

Were you surprised that you had never designed a movie set in New York before? What’s your connection to the city?

I came here to attend Cooper Union in '64 and '65. I lived on Tompkins Square, which is somewhat near the Lower East Side but not quite as far down as Orchard Street. The city is vastly different now compared to the ’60s, which were actually more reminiscent of the ’50s, as it hadn’t undergone rapid changes yet. Each visit to the city brings an invigorating rush of energy—the art, the people, the music. While I attended Cooper Union, just across the street was the Five Spot Café, where Thelonious Monk regularly performed. Andy Warhol’s factory was only half a block away on St. Mark’s, and Fillmore East hosted numerous rock stars. The art galleries and museums were exceptional. I’ve always wanted to work here but rarely had the chance. In 197

Other articles

safeguarding Family at Any Cost: An Exclusive Interview with Lee Byung-hun on No Other Choice

Robert Kojder speaks with Lee Byung-hun, the star of No Other Choice... This year has been quite eventful for him, ranging from voiceover roles in the highly popular animated feature K-Pop Demon Hunters to delivering a thrilling performance...

safeguarding Family at Any Cost: An Exclusive Interview with Lee Byung-hun on No Other Choice

Robert Kojder speaks with Lee Byung-hun, the star of No Other Choice... This year has been quite eventful for him, ranging from voiceover roles in the highly popular animated feature K-Pop Demon Hunters to delivering a thrilling performance...

Jordan Raup’s Best 10 Films of 2025

In conjunction with The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2025, our contributors are presenting their individual top 10 lists as part of our year-end coverage. Amid a year marked by significant upheaval in Hollywood, it has become evident that despite the profit-oriented approaches of influential executives that undermine the art they claim to cherish, filmmakers will still continue to create.

Jordan Raup’s Best 10 Films of 2025

In conjunction with The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2025, our contributors are presenting their individual top 10 lists as part of our year-end coverage. Amid a year marked by significant upheaval in Hollywood, it has become evident that despite the profit-oriented approaches of influential executives that undermine the art they claim to cherish, filmmakers will still continue to create.

Jack Fisk on Crafting an Authentic 1950s New York for Marty Supreme and Josh Safdie’s Drive

Throughout the last fifty years, production designer Jack Fisk has worked with a notable lineup of writer-directors such as Terrence Malick, David Lynch, Brian De Palma, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Alejandro González Iñárritu. A few years back, when he recreated 1920s Fairfax, Oklahoma for Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, it was somewhat of a surprise.