Rotterdam Review: Chronovisor Reveals the Greatest Untold Conspiracy

It's a grand story reminiscent of a Borges narrative, the most outlandish conspiracy theory you've probably never encountered. In the 1960s, Italian Benedictine monk Pellegrino Ernetti asserted that he had created a machine enabling one to view and photograph the past. Constructed from cathode rays, enigmatic metals, and various peculiar antennas, the “chronovisor” didn't exactly allow time travel but instead captured and presented ancient occurrences like a sort of supernatural television. Alongside the twelve scientists who supposedly assisted him in its development—a group rumored to include Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi and former Nazi engineer Wernher von Braun—Ernetti allegedly "witnessed" and documented remarkable events, ranging from the establishment of the Roman Empire to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Or so he claimed. Despite a vow to remain silent about the invention—due to a request from Pope Pius XII himself—the monk eventually revealed the secret, leading to numerous articles in Italian newspapers during the 1970s that were both fascinated by the priest and eager to debunk his tale as mere urban legend. Was it? Shortly before his death in 1994, Ernetti wrote a letter reaffirming the reality of the chronovisor. He stated that Pope Pius XII had prohibited him from discussing it due to fears that the device could bring about humanity's destruction, claiming that the Vatican had only concealed it rather than destroyed it.

Whether true or fabricated, Jack Auen and Kevin Walker understand that this tale is ripe for endless and compelling speculation, and their impressive feature debut, Chronovisor, treats the titular machine as both a sacred quest and a black hole drawing in those who come into its vicinity. At its core, this is the saga of Béatrice Courte, an academic—portrayed by real-life scholar Anne Laure Sellier—who comes across a fleeting mention of the device and becomes fixated on tracking it down. Yet, Chronovisor unfolds as a ghost story—not solely because the driving force remains largely unseen, but also because its images resonate with whispers of enigmas. The film's ambiance, from dim lighting to textured visuals (shot in warm, low-lit Super 16mm by Leo Zhang), evokes a universe suspended between the worlds of the living and the dead.

This is not the first time Auen and Walker have delved into the occult. Their 2021 short film, Marblehead, followed a man residing in a cemetery; and their upcoming 2025 film, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, co-directed by Walker and Irene Zahariadis, tracked a few elderly residents of a remote Greek village as they transported their ancestors' remains to a mausoleum. However, what sets Chronovisor apart, and lends it a romantic quality, is the significance Auen and Walker ascribe to the act of reading: this film posits that the secret to the most extraordinary story not yet told can be found not through online searches, but through long nights spent hunched over books in a library.

If this idea seems somewhat out of place, it's because the entire film carries that essence. Set ostensibly in the present, Chronovisor continually disrupts your sense of time. With the exception of occasional smartphones, the "action" unfolds in a timeless world (when Béatrice reaches out to one of Ernetti's surviving relatives, she sends a handwritten letter rather than an email). The narrative gradually shifts focus from the academic-turned-detective to the media she explores: we hear recordings of a lecture Ernetti delivered about his invention, watch archival TV footage concerning him and other individuals who attempted to communicate with the deceased, but primarily we read. Chronovisor is so enamored with the written word that close-ups of books and articles comprise the bulk of its runtime—English translations of their various languages are presented not as subtitles but directly layered over the original text on pages. This choice is not made lightly: Auen and Walker intend for viewers to read alongside Béatrice, and what is striking about their film is the way it tries to meld two different art forms (literature and cinema) and two distinct actions (reading and watching), all while adapting its rhythm to accommodate both.

Chronovisor—“an armchair mystery,” as its writers-directors have dubbed it—boldly demands its 21st-century, perpetually online audience to fully engage with something as seemingly static as a printed page. Nonetheless, nothing about it is ever truly inactive—especially not the scenes where Zhang focuses on books and articles. The predominance of written words in Chronovisor stems from the film’s strong belief that they serve as the ultimate vessels of secrets, particularly for something as astounding as Ernetti's creation. So persuasive is this conviction that viewers may find themselves squinting to avoid missing any clues, leading to a dizzying effect as the narrative shifts from libraries to the streets of New York

Other articles

Touchdown: The 12 Greatest Football Films Ever

Touchdown — these are the greatest football films we've ever witnessed.

Sundance Review: Hanging by a Wire is a Fast-Paced Docu-Thriller but Falls Short on Depth

A fast-paced docu-thriller, Mohammed Ali Naqvi’s Hanging by a Wire captures human drama and excitement, although it could delve deeper into the complexities of the individuals it portrays. The film appears to concentrate more on a dramatic rescue rather than exploring preventive measures to avoid similar situations in the future. It incorporates archival footage, including mobile phone recordings,

Touchdown: The 12 Greatest Football Films Ever

Touchdown — these are the greatest football films we've ever witnessed.

Sundance Review: Hanging by a Wire is a Fast-Paced Docu-Thriller but Falls Short on Depth

A fast-paced docu-thriller, Mohammed Ali Naqvi’s Hanging by a Wire captures human drama and excitement, although it could delve deeper into the complexities of the individuals it portrays. The film appears to concentrate more on a dramatic rescue rather than exploring preventive measures to avoid similar situations in the future. It incorporates archival footage, including mobile phone recordings,

Sundance Review: If I Go Will They Miss Me Discovers Poetic Elegance in the Journey to Adulthood

Discovering poetic beauty in the everyday, Walter Thompson-Hernández’s If I Go Will They Miss Me focuses on the journey to adulthood within the housing projects of southern Los Angeles. While life in these areas is frequently portrayed with a harshness that highlights a life-or-death mentality, this promising new director adopts a contrasting perspective—one in which dreams

Sundance Review: If I Go Will They Miss Me Discovers Poetic Elegance in the Journey to Adulthood

Discovering poetic beauty in the everyday, Walter Thompson-Hernández’s If I Go Will They Miss Me focuses on the journey to adulthood within the housing projects of southern Los Angeles. While life in these areas is frequently portrayed with a harshness that highlights a life-or-death mentality, this promising new director adopts a contrasting perspective—one in which dreams

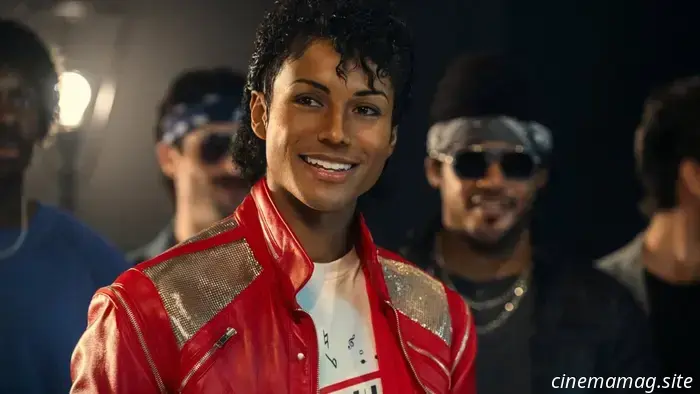

The biopic about Michael Jackson, titled "Michael," has released a new trailer and promotional posters.

Lionsgate has unveiled a new trailer and posters for Antoine Fuqua's forthcoming biopic, Michael, which depicts the life of the King of Pop, both on and off the stage.

The biopic about Michael Jackson, titled "Michael," has released a new trailer and promotional posters.

Lionsgate has unveiled a new trailer and posters for Antoine Fuqua's forthcoming biopic, Michael, which depicts the life of the King of Pop, both on and off the stage.

Maika Monroe travels to Raccoon City in a stunning live-action short film for Resident Evil Requiem.

As we move into the month of its release, Capcom has revealed an exciting short film trailer for Resident Evil Requiem, featuring Longlegs and horror star Maika Monroe from It Follows, portraying a mother who tries…

Maika Monroe travels to Raccoon City in a stunning live-action short film for Resident Evil Requiem.

As we move into the month of its release, Capcom has revealed an exciting short film trailer for Resident Evil Requiem, featuring Longlegs and horror star Maika Monroe from It Follows, portraying a mother who tries…

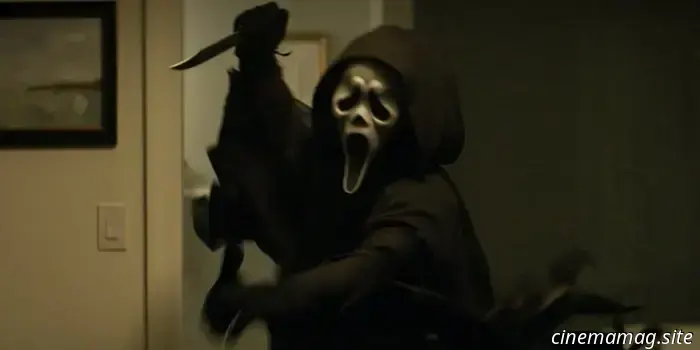

Fear comes close to home for Sidney in the Super Bowl TV spot for Scream 7.

In anticipation of this Sunday’s Super Bowl, Paramount Pictures has released a Big Game advertisement for Scream 7, featuring Sidney being confronted by her past as Ghostface sets their sights on her daughter Tatum. Che…

Fear comes close to home for Sidney in the Super Bowl TV spot for Scream 7.

In anticipation of this Sunday’s Super Bowl, Paramount Pictures has released a Big Game advertisement for Scream 7, featuring Sidney being confronted by her past as Ghostface sets their sights on her daughter Tatum. Che…

Rotterdam Review: Chronovisor Reveals the Greatest Untold Conspiracy

It's a tall story reminiscent of a Borges narrative, the most outlandish conspiracy theory you've likely never encountered. In the 1960s, Italian Benedictine monk Pellegrino Ernetti asserted that he had created a device enabling people to view and capture images of the past. This apparatus, composed of cathode rays, enigmatic metals, and various peculiar antennas, was called the “chronovisor.”