Ben Burtt on the Decline of Sensitivity to Sound in Modern Hollywood, Including Lightsabers and the Wilhelm Scream

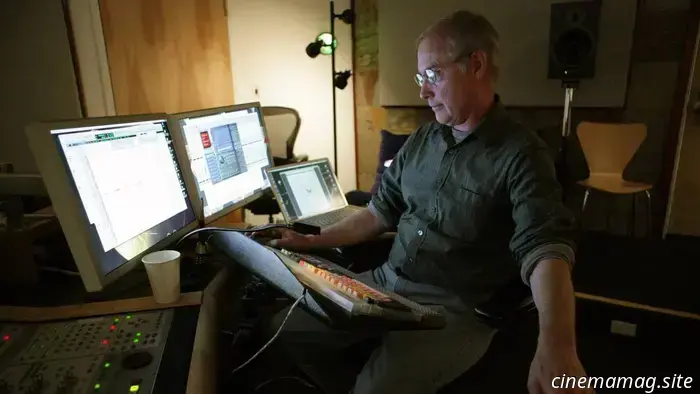

It’s mid-July and I’m relaxing in my living room, contemplating what Ben Burtt, a key figure behind some of the most cherished cultural creations of the 20th century, might think of my decor. He appears on my screen from Locarno, where he has just received a lifetime achievement award. I genuinely express my gratitude for his contributions to cinema, and something in my phrasing causes him to blush.

Burtt was born in Jamestown, New York, in 1948. Like many of his peers, he began his career at Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, working on sound effects for the trailer of Death Race 2000. His credits subsequently read like a highlights reel of American pop culture. In his role as sound designer, Burtt is known for crafting Chewbacca’s roar, the lightsaber’s hum, and Indiana Jones’ whip crack. In the 1970s, he started an inside joke with colleagues that later became known as the Wilhelm Scream. He won Oscars for his work on Raiders of The Lost Ark, E.T., and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade while collaborating with Steven Spielberg. When Wall-E speaks, it's reminiscent of Burtt; likewise, Darth Vader’s breathing is also his creation.

In our discussion, Burtt conveys a warm sense of humility often associated with his generation of behind-the-scenes Hollywood artisans—artists who viewed a life in film more as a profession than a calling. For more than 25 minutes (edited for clarity here), we chatted about his early experiences in the industry, the sounds he enjoys and dislikes in movies, and his endeavor to record Abraham Lincoln’s pocket watch. But first, I start with the most straightforward question.

The Film Stage: I’d like to begin by discussing one of your earliest films. When I was 14, I bought a DVD of Death Race 2000 and probably watched it twenty times. It was fascinating to later understand its significance, for both Corman and you. How did you become involved in that project? You must have been around 25 at that time?

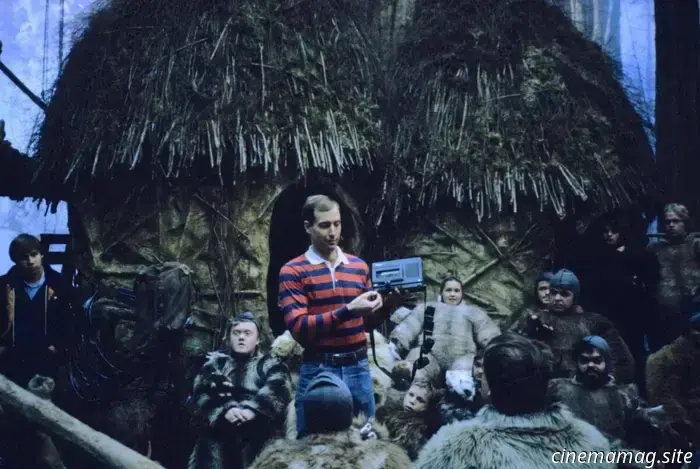

Ben Burtt: I had just finished my graduate studies at the University of Southern California film school, seeking experience and a source of income. A fellow student and I realized we could quickly find work as sound editors for very low-budget films being produced in the lesser-known parts of Hollywood. Richard Anderson, my friend, was working on sound for New World Pictures at the time, which was Corman’s company, and they were producing Death Race. They needed sound for those futuristic cars and knew I was passionate about sound effects, so they asked me to create a library of exotic car sounds. The first sounds I produced were for the trailer, edited by Joe Dante, who would go on to be a celebrated director but was then a stressed-out young man working with a Moviola. I spent two weeks compiling sounds from planes and other unique motors in my collection. That was the first film where I contributed sound in Hollywood.

Did you keep in contact with Corman?

I actually didn’t meet Corman then. I was aware of him, of course, and like most students, I had grown up watching his low-budget exploitation films. It wasn’t until a few years later, after I had worked on Star Wars, that I had a pleasant meeting with him. I was flying to New York, and we happened to sit next to each other. I recognized him, and, oddly enough, he recognized me. He congratulated me on my success. When I mentioned my work on Death Race, he replied, “Oh yes, I remember! We loved those sounds.” Receiving a compliment from Roger felt special since I admired his work. We all appreciate the underdog filmmaker, those who can produce something entertaining despite many limitations.

Do people ever ask you to mimic Wall-E's voice?

Wall-E is essentially my voice altered electronically, so I can’t replicate it live. Ironically, mothers often approach me with their five-year-olds, typically a little girl, and the mother will say, “Do Wall-E for Ben,” and the child will perfectly respond, “Wall-eeeee.” I'm not sure why they chose me. Humans are excellent at impersonation; once we hear something, we can easily mimic it.

I’m curious, after such a lengthy career, are there still moments when you hear something in a film and find yourself thinking, “Wow, that’s impressive,” or “that’s intriguing,” or “that’s clever”?

Not as frequently as before, but there are films that truly stand out to me with fascinating material. I still engage with cinema as if I were a film student. You learn to appreciate films on two levels: one for entertainment or emotional impact, while simultaneously maintaining an awareness of the processes involved—especially when it’s someone you know. I certainly admire Richard King’s work on Master and Commander, a Peter Weir film that I believe

Other articles

11 Remarkable Films Where Little Action Occurs

Here are 11 remarkable films where not much seems to occur. Or is it? While there may be a scarcity of car chases, murders, sexual encounters, or explosions, lives are subtly

11 Remarkable Films Where Little Action Occurs

Here are 11 remarkable films where not much seems to occur. Or is it? While there may be a scarcity of car chases, murders, sexual encounters, or explosions, lives are subtly

The 12 Greatest Movie Plot Twists of All Time, Ranked

Here are the greatest movie plot twists of all time, ranked. As you will notice, we generally favor twists that transform the narrative of a film rather than those that conclude it. However, we

The 12 Greatest Movie Plot Twists of All Time, Ranked

Here are the greatest movie plot twists of all time, ranked. As you will notice, we generally favor twists that transform the narrative of a film rather than those that conclude it. However, we

Nicole Kidman Reveals a Hidden Truth in the Premiere Trailer for Holland.

Having been in development for quite some time, with Errol Morris set to direct as far back as 2013, the thriller Holland (previously titled Holland, Michigan) finally began production in the spring of 2023, directed by Mimi Cave (Fresh). Starring Nicole Kidman, Gael García Bernal, Matthew Macfadyen, and Jude Hill, it will now

Nicole Kidman Reveals a Hidden Truth in the Premiere Trailer for Holland.

Having been in development for quite some time, with Errol Morris set to direct as far back as 2013, the thriller Holland (previously titled Holland, Michigan) finally began production in the spring of 2023, directed by Mimi Cave (Fresh). Starring Nicole Kidman, Gael García Bernal, Matthew Macfadyen, and Jude Hill, it will now

The trailer for season 2 of Star Wars: Andor hints at the return of some recognizable allies and adversaries.

It seems like ages since we last visited this galaxy far, far away, but Disney has finally unveiled the trailer for the second season of their highly praised Star Wars series, Andor. This twelve-episode finale continues the story of Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) and the rising rebel alliance over the dramatic four years. [...]

The trailer for season 2 of Star Wars: Andor hints at the return of some recognizable allies and adversaries.

It seems like ages since we last visited this galaxy far, far away, but Disney has finally unveiled the trailer for the second season of their highly praised Star Wars series, Andor. This twelve-episode finale continues the story of Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) and the rising rebel alliance over the dramatic four years. [...]

Flickering Myth and Shepka Productions have announced the suspense thriller Death Among the Pines.

Following their recent partnership on the gothic horror film The Baby in the Basket (currently available in the US and UK), Flickering Myth, Shepka Productions, and Jolliffe Productions have revealed that their next project, Death Among the Pines, is set to commence production next month, aiming for a release in 2026. The screenplay is written by genre author Tom […]

Flickering Myth and Shepka Productions have announced the suspense thriller Death Among the Pines.

Following their recent partnership on the gothic horror film The Baby in the Basket (currently available in the US and UK), Flickering Myth, Shepka Productions, and Jolliffe Productions have revealed that their next project, Death Among the Pines, is set to commence production next month, aiming for a release in 2026. The screenplay is written by genre author Tom […]

Netflix has released a trailer for Adolescence featuring Stephen Graham, Ashley Walters, and Erin Doherty.

Netflix has unveiled a trailer, poster, and images for the limited crime drama series titled Adolescence. Featuring Stephen Graham, Ashley Walters, Erin Doherty, and Owen Cooper, the series centers on a detective, a therapist, and the parents of a 13-year-old boy as they seek answers following his arrest for the murder of another student from […]

Netflix has released a trailer for Adolescence featuring Stephen Graham, Ashley Walters, and Erin Doherty.

Netflix has unveiled a trailer, poster, and images for the limited crime drama series titled Adolescence. Featuring Stephen Graham, Ashley Walters, Erin Doherty, and Owen Cooper, the series centers on a detective, a therapist, and the parents of a 13-year-old boy as they seek answers following his arrest for the murder of another student from […]

Ben Burtt on the Decline of Sensitivity to Sound in Modern Hollywood, Including Lightsabers and the Wilhelm Scream

It’s mid-July, and I’m in my living room, contemplating what Ben Burtt, the person behind many cherished cultural creations of the 20th century, might think of the decor. He appears on my screen from Locarno, where he has just been honored with a lifetime achievement award. I begin by sincerely expressing my gratitude to him.