Cannes Review: Koji Fukada’s Love on Trial Elegantly Explores Idol and Autonomy

What is love? For some, it represents mutuality—a chemistry, care, and concern that flourishes into a mutually supportive relationship. For others, it signifies devotion—a one-sided, obsessive love that the admirer perceives as selfless.

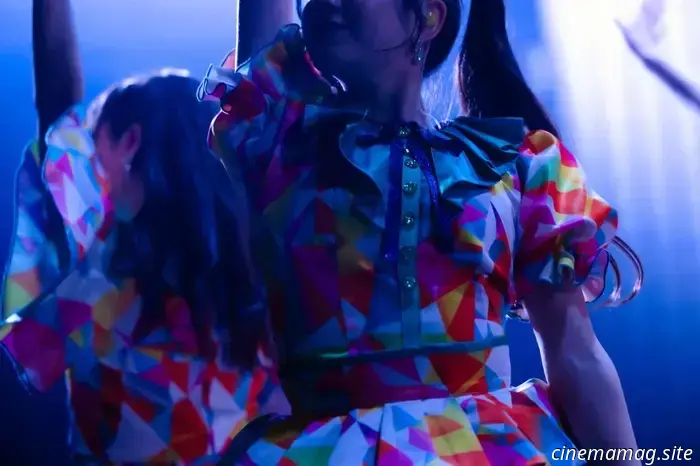

The Japanese idol group Happy Fanfare sings about love, even though they are prohibited from pursuing it themselves—such is the "No Love" clause in their contracts. This romantic isolation is considered essential for the business of idol fame, enabling their male fans to cling to the fantasy of a reachable yet unreachable female. This notion is reinforced through meet-and-greet events where the group reminisces about fans’ previous gifts and messages, fostering a parasocial relationship that begins to fracture when reality intervenes.

Koji Fukada (Harmonium, A Girl Missing) is recognized in the festival circuit for his cool, often unsettling character dramas that disrupt family dynamics. Love on Trial marks a shift: a heartfelt, Hamaguchi-influenced film in two parts that expands his creative range to align with an increasingly openly political cinematic landscape.

As charismatic young women, it's only expected that the five members of Happy Fanfare would meet similarly engaging young men. The group's junior member, Nanako, develops a friendship with a male YouTuber, and trouble arises when photos of them singing karaoke together are made public. The group's agency reminds the girls that interactions with the opposite sex are strictly prohibited, leading to Nanako being sent back to her parents while the higher-ups attempt to repair her image.

In the midst of this, group leader Mai (Kyoko Saito) strikes up a friendship with street performer Kei (Yuki Kura) after they lock eyes in a local park. Kei is her Tuxedo Mask to her Sailor Moon, a fellow performer who understands the pressures of an audience. However, their lives differ significantly; Kei is under far less supervision—being male and comparatively low-profile. He keeps an eye on Mai while living in a compact camper van, present whenever she needs him. As the backlash against Nanako escalates to a violent incident (a shocking scene reminiscent of Satoshi Kon's Perfect Blue), Mai reaches her breaking point—she can no longer suppress the love that gives her life meaning and encompasses her entirely. In front of her groupmates and managers, Mai runs to him.

Both Mai and Kei are sued by the agency for breaching the No Love clause, leading to a gripping exploration of the legal issues stemming from her choice. Fukada and co-writer Shintaro Mitani portray these struggles with a sharp focus on the chemistry and daily moments between the couple. Their lives and love are strikingly ordinary, capturing our hearts and empathy through their relatability—the so-called crime is their love for each other.

Fukada conceived Love on Trial when a real-life case similar to this made headlines a decade ago. It feels timely for this film to come out now, in a post-MeToo industry that is increasingly striving to empower female talent. The casting is deliberate and meaningful: lead Kyoko Saito is a former idol from the group Hinatazaka46, who has since retired; Yuki Kura has also worked as a model; and Erika Karata, who portrays the group's manager, has experience with gender-related media scrutiny as a Hamaguchi alum (Asako I & II).

Their performances are subtle, as is the film that surrounds them. This is an idol narrative that only intermittently sparks excitement. There are no grand dramatic confrontations—just the gradual suffocation of an industry that restricts these characters and the shining catharsis of a personal love that yearns to liberate them. These events accumulate in the viewers' minds, with anger solidifying as the injustice becomes evident. Fukada quietly underscores that these events are all too real, and these characters are merely human.

Your level of confusion upon facing these realities may differ. Many European viewers at the Cannes premiere appeared puzzled; some even walked out. Love on Trial does not simplify concepts for international audiences by over-explaining what an idol group is or the historical context of their management. Instead, Fukada presents clear elements and examples that highlight the intricate business dynamics between artists and audiences in Japan, making the film akin to evidence in a trial from which we can derive our own insights.

Love on Trial premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

Cannes Review: Koji Fukada’s Love on Trial Elegantly Explores Idol and Autonomy

What is love? For some, it signifies mutuality—a chemistry, care, and concern that flourishes into a relationship marked by equal support. For others, it represents devotion—a one-sided, obsessive affection that the lover perceives as selfless. The Japanese idol group Happy Fanfare sings about love, yet they are prohibited from seeking their own due to the "No Love" clause in place.