Venice Review: Pin de Fartie Offers a Whimsical and Mind-Bending Interpretation of Samuel Beckett

Since the early 2000s, the highly independent Argentine filmmaking group El Pampero Cine has crafted a unique filmography by challenging traditional norms. Their catalogue, which features Mariano Llinás’ 13.5-hour La Flor and Laura Citarella’s 4.5-hour Trenque Lauquen, isn't exactly straightforward. However, those who resonate with Pampero's style will confirm the uniquely rewarding experience of engaging with their films. Pin de Fartie, the most recent work by co-founder Alejo Moguillansky, has a more manageable runtime of 106 minutes. Despite its brevity, it expands upon and dissects one of the 20th century's most iconic absurdist plays in a mind-bending manner.

The play in question is Samuel Beckett’s Fin de Partie (known as Endgame in English), which debuted in 1956. This highly experimental, one-act tragicomedy takes place in a single room featuring four characters who engage in banter while grappling with the despair and meaninglessness of existence. Pin de Fartie begins with a scene reminiscent of the play's environment— a blind man reprimanding his servant/caretaker with mundane, repetitive questions and responses—but here, the target of the blind man's (Otto's) irritation is a girl named Cleo. It's clear this isn't simply a modern retelling of the source material when the camera shifts to a group narrating and providing sound effects. The situation becomes even more complex as this same group starts narrating "variants" of Beckett’s story—one where two actors meet weekly to rehearse Fin de Partie and another in which a blind woman asks her son to read the play to her. Along with the meta quality of the entire setup, the destinies of the characters start to shift from their literary counterparts in surprising ways.

Given that this is an El Pampero Cine production, it's no surprise that the film is quite esoteric in both its conception and execution. Viewers unfamiliar with Fin de Partie or Beckett’s philosophical views may find it challenging to engage with the film; the excessively wordy dialogue, which includes entire sections taken directly from the original play, does not aid its accessibility. Still, there’s an authentic playfulness and inventiveness in how Moguillansky and co-writers Luciana Acuña and Mariano Llinás reinterpret a 70-year-old text dealing with existential dread. The absurdity of Otto and Cleo’s circumstances is highlighted to bring out the humor in Beckett’s language. Although the characters exhibit frustration from feeling trapped and powerless to change their surroundings, the sheer triviality of their rapid exchanges ("What time is it?" "The usual.") reveals the artificiality of their world, providing sharp comedic relief.

The section about rehearsals presents a completely different tone. As the two actors embody the characters created by Beckett, they begin to question whether their feelings for each other are genuine or preordained. Over time, their weekly sessions evolve into a profound inquiry into performance and authenticity, striking an unexpectedly emotional chord.

Next is perhaps the most surreal segment: the blind woman and her son. Here, the dutiful son begins to notice parallels between the play he is reading and his own life. To understand what this means (and whether his mother is trying to imply something through Beckett), he embarks on a personal investigation regarding his identity. This is where the wild originality characteristic of Pampero productions truly emerges. From the man's discovery of a tennis player who bears a striking resemblance to him to deciphering the phrase tattooed on his double's arm, the narrative takes such an unusual turn that it almost feels like an entirely different film. This willingness to forsake logic and conventional storytelling—embracing the small enigmas of life—imbues films like Pin de Fartie with an additional spark, allowing viewers to experience the exhilaration of witnessing something truly imaginative.

The film transitions fluidly between segments, connected by glimpses into the recording studio where an omniscient narrator exerts a god-like oversight over unsuspecting subjects. This narrative technique cleverly illustrates the totalitarian nature of storytellers and adds depth to Beckett’s contemplation of humanity's inability to initiate change. However, Moguillansky presents a far less fatalistic view. In the film's concluding moments, each character reaches some form of realization, breaking free from cycles of dependence and despair. Fin de Partie fundamentally explores our inability to dictate our own endings. By placing its characters in a world envisioned by Beckett while granting them the agency to diverge from the script, Pin de Fartie transforms into an uplifting, subtly profound counterargument to the text it skillfully reinterprets for the screen.

Pin de Fartie premiered at the 2025 Venice Film Festival.

Other articles

The Grabber has returned from the dead in the trailer for The Black Phone 2.

Universal Pictures and Blumhouse have unveiled the complete trailer for director Scott Derrickson’s horror sequel, The Black Phone 2. The story focuses on Finn four years after he managed to escape from and slay his captor, The Grabber. As the malevolent child killer rises from the dead, he begins to haunt Finn’s younger sister, Gwen, as she starts […]

The Grabber has returned from the dead in the trailer for The Black Phone 2.

Universal Pictures and Blumhouse have unveiled the complete trailer for director Scott Derrickson’s horror sequel, The Black Phone 2. The story focuses on Finn four years after he managed to escape from and slay his captor, The Grabber. As the malevolent child killer rises from the dead, he begins to haunt Finn’s younger sister, Gwen, as she starts […]

First Trailer for Ildikó Enyedi's Silent Friend Links Léa Seydoux and Tony Leung

In a collision of global talent that seems to be becoming more uncommon, Ildikó Enyedi has united Léa Seydoux and Tony Leung for Silent Friend, which “narrates three tales linked to a tree spanning more than a century” and (somewhat ambitious) focuses on “significant changes in human understanding of plants, animals, and people.” In

First Trailer for Ildikó Enyedi's Silent Friend Links Léa Seydoux and Tony Leung

In a collision of global talent that seems to be becoming more uncommon, Ildikó Enyedi has united Léa Seydoux and Tony Leung for Silent Friend, which “narrates three tales linked to a tree spanning more than a century” and (somewhat ambitious) focuses on “significant changes in human understanding of plants, animals, and people.” In

Hot Toys has revealed a sixth scale figure of Sergeant Hound from Star Wars: The Clone Wars.

Hot Toys has unveiled the sixth scale collectible figure of Sergeant Hound from the episode “The Jedi Who Knew Too Much” in the fifth season of the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars. The set also includes a figure of his massiff, Grizzer. Take a look at the promotional images here… SEE ALSO: Clone Commando Gregor joins […]

Hot Toys has revealed a sixth scale figure of Sergeant Hound from Star Wars: The Clone Wars.

Hot Toys has unveiled the sixth scale collectible figure of Sergeant Hound from the episode “The Jedi Who Knew Too Much” in the fifth season of the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars. The set also includes a figure of his massiff, Grizzer. Take a look at the promotional images here… SEE ALSO: Clone Commando Gregor joins […]

TIFF Review: Mile End Kicks Tracks a Canadian Music Critic's Journey of Self-Discovery

There's a reason why Alanis Morissette's Jagged Little Pill resonates with Grace Pine (Barbie Ferreira). It's the same reason her proposal charms a publisher into giving her an advance and a contract for a 33 1/3 book on the topic: the feminist anger; the authenticity; and the reality that the world was ready to invest millions.

TIFF Review: Mile End Kicks Tracks a Canadian Music Critic's Journey of Self-Discovery

There's a reason why Alanis Morissette's Jagged Little Pill resonates with Grace Pine (Barbie Ferreira). It's the same reason her proposal charms a publisher into giving her an advance and a contract for a 33 1/3 book on the topic: the feminist anger; the authenticity; and the reality that the world was ready to invest millions.

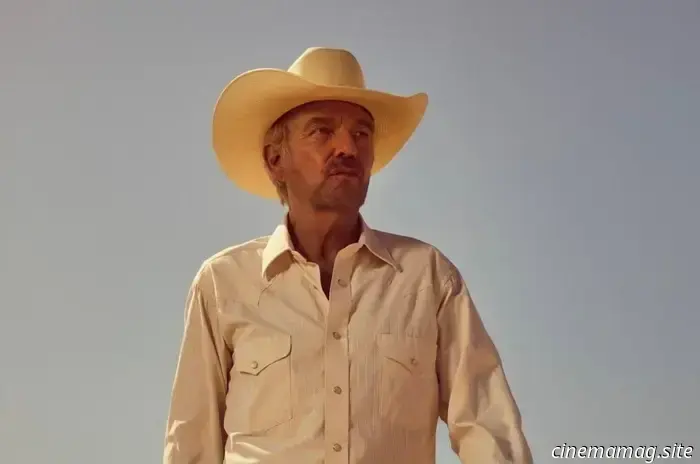

Paramount+ has released the trailer and promotional images for season 2 of Landman.

Paramount+ has unveiled a trailer for the second season of Taylor Sheridan’s (Yellowstone) highly regarded drama series Landman. The cast includes Billy Bob Thornton, Demi Moore, Sam Elliott, Andy Garcia, Ali Larter, Jacob Lofland, Michelle Randolph, Paulina Chávez, Kayla Wallace, Mark Collie, James Jordan, and Colm Feore. You can watch the season 2 trailer below… The story takes place in […]

Paramount+ has released the trailer and promotional images for season 2 of Landman.

Paramount+ has unveiled a trailer for the second season of Taylor Sheridan’s (Yellowstone) highly regarded drama series Landman. The cast includes Billy Bob Thornton, Demi Moore, Sam Elliott, Andy Garcia, Ali Larter, Jacob Lofland, Michelle Randolph, Paulina Chávez, Kayla Wallace, Mark Collie, James Jordan, and Colm Feore. You can watch the season 2 trailer below… The story takes place in […]

Review of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds Season 3 Episode 9 - 'Terrarium'

Chris Connor critiques the ninth episode of season 3 of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds… The series has consistently paid tribute to the original 1960s show that launched the franchise, all while navigating its own unique path through uncharted territories. The second-to-last episode of this season directly honors the […]

Review of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds Season 3 Episode 9 - 'Terrarium'

Chris Connor critiques the ninth episode of season 3 of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds… The series has consistently paid tribute to the original 1960s show that launched the franchise, all while navigating its own unique path through uncharted territories. The second-to-last episode of this season directly honors the […]

Venice Review: Pin de Fartie Offers a Whimsical and Mind-Bending Interpretation of Samuel Beckett

Since the early 2000s, the highly independent Argentine filmmaking group El Pampero Cine has crafted a unique filmography by rejecting traditional norms. With titles such as Mariano Llinás' 13.5-hour La Flor and Laura Citarella's 4.5-hour Trenque Lauquen, their catalog is certainly unconventional. However, those who resonate with Pampero's rhythm will confirm its distinctively gratifying experience.