Rotterdam Review: Tycoon is an Impressive Depiction of a City in Flames.

In a brief moment from Charlotte Zhang’s *Tycoon*, a young man reveals that he stopped reporting the cockroaches infesting his Los Angeles apartment to his landlord for fear of the entire building being condemned—an outcome shared by numerous other buildings in the city, which are then sold off to greedy property developers. The film is set in the future, specifically 2028, as L.A. prepares for the Summer Olympics. Deadly livestock viruses have turned genetically modified insects into the nation’s main protein source, while a massive cockroach infestation sparks waves of property disputes. However, Zhang’s dystopian vision reflects a historical backdrop that echoes what Thomas Pynchon described as the “long, sad history of L.A. land use”—a city that rapidly transforms, continually displacing the poor to accommodate the wealthy in an ongoing cycle of upheaval. *Tycoon* captures some of this urgency without succumbing to it; a fierce anger permeates the narrative, mirrored by the film’s dynamic characters as well as its vibrant style. Blending elements of coming-of-age and political thriller, *Tycoon* feels like it could explode at any moment. “Something’s about to happen,” a young woman predicts midway through, providing an apt summary.

Zhang, who experienced an illegal eviction from her L.A. apartment due to a roach problem, has mentioned Charles Burnett’s *Killer of Sheep* as an influence. Her feature debut, which was filmed intermittently over weekends with friends, unfolds as a collection of vignettes instead of a traditional three-act structure. If *Tycoon* can be said to have a central narrative, it revolves around two young grifters from Los Angeles (Miguel Padilla-Juarez and Jon Lawrence Reyes) attempting to survive and earn money as modern-day pirates. We observe them hijacking delivery robots to enjoy stolen groceries, reselling insect powder ($60 per bag!), and plotting their escape from the city.

Yet the film frequently diverts its focus, zooming out from their escapades to explore the city of L.A. itself. Ominous radio broadcasts accompany remnants of the city’s history. There are clips from August 1984, the last Olympic Games held in L.A.; a faded postcard of Mulholland Memorial Fountain; and black-and-white illustrations capturing pivotal moments in California’s 20th-century history, from the gold rush to labor strikes and the Great Depression. Throughout, Zhang introduces title cards, which act as political slogans and rallying cries rather than conventional chapter titles—“Rehearsing the Republic,” “Everyone’s A Winner,” “Spit Down the Cliff Once You’ve Made It Up and Call it Rain”—distributing *Tycoon* in a manner reminiscent of intertitles in Godard’s films. This approach sometimes lends *Tycoon* a quality of being more of a statement than a conventional film. It highlights the people L.A. displaces and their stories, intertwined with a long history of struggles for the right to remain: don’t let them perish.

Like her aimless characters, Zhang is engaged in her own battle, forging a space for cinema that need not conform to conventional storytelling. *Tycoon* disregards deep character development; despite the shared thoughts of Padilla-Juarez and Reyes—some expressed to each other, some relayed to us via introspective voiceover—the boys remain purposefully enigmatic, embodying little more than their undefined fears and hopes. Without being preachy, *Tycoon* illustrates how people are inextricably influenced by their environments. It makes sense that Zhang presents the two friends as paranoid wanderers, driven not by aspirations but by an overwhelming desire for vengeance. But vengeance against what? The challenges they face are much larger than the familiar figures of local authority, and the film skillfully conveys that constant, unseen threat—the way the atmosphere is charged with ominous signs. *Tycoon* flirts with genre conventions only to eschew them, transforming into something more exhilarating: a tempestuous record of the city as viewed by those cast aside to its outskirts.

The premise and Olympic setting evoke Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina’s influential *Oiga Vea*, which examines the 1971 Pan American Games in Cali, Colombia, through the eyes of those unable to access the stadiums. The film’s textures also reflect the intense ambiance and digital experimentation characteristic of David Lynch’s *Inland Empire*. Zhang’s portrayal of L.A. is starkly different from the typical picturesque representations of the city (much of the film’s action unfolds amid unremarkable warehouses, backyards, and rooftops far from its glitzy areas). Zhang—who wrote, directed, edited, and filmed *Tycoon*—weaves together archival, iPhone, Super 8, and MiniDV footage into a collage that prioritizes interrogating the anxious climate haunting its characters rather than fleshing them out.

Other articles

Hasbro has revealed the action figures of Lord Starkiller and Misty & Cav from Star Wars: The Black Series.

Hasbro has officially started pre-orders for two new releases in the Star Wars: The Black Series, including the Gaming Great Lord Starkiller figure from the popular video game Star Wars: The Force Unleashed.

Hasbro has revealed the action figures of Lord Starkiller and Misty & Cav from Star Wars: The Black Series.

Hasbro has officially started pre-orders for two new releases in the Star Wars: The Black Series, including the Gaming Great Lord Starkiller figure from the popular video game Star Wars: The Force Unleashed.

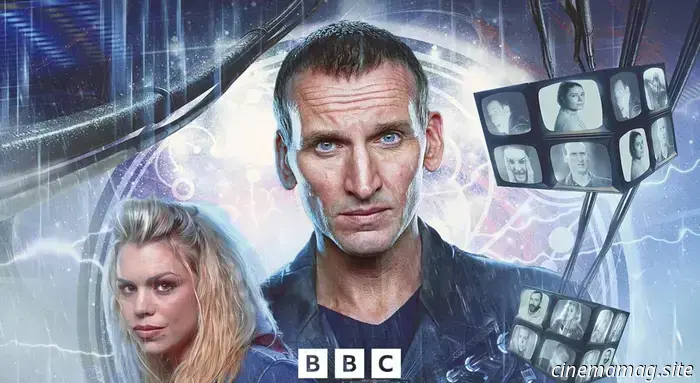

A new Doctor Who adventure sends The Ninth Doctor and Rose to Cloud Eight.

Big Finish has unveiled the newest audio adventure featuring Christopher Eccleston’s Doctor, titled The Ninth Doctor Adventures: Cloud Eight. This recent installment is penned by Lauren Mooney and Stew…

A new Doctor Who adventure sends The Ninth Doctor and Rose to Cloud Eight.

Big Finish has unveiled the newest audio adventure featuring Christopher Eccleston’s Doctor, titled The Ninth Doctor Adventures: Cloud Eight. This recent installment is penned by Lauren Mooney and Stew…

Elizabeth Banks stars as The Miniature Wife in the trailer for the Peacock comedy series.

NBC Peacock has released the trailer for The Miniature Wife, their dramedy series featuring Elizabeth Banks (The Hunger Games), who inadvertently becomes miniature due to her scientist husband's actions, portrayed by Mat…

Elizabeth Banks stars as The Miniature Wife in the trailer for the Peacock comedy series.

NBC Peacock has released the trailer for The Miniature Wife, their dramedy series featuring Elizabeth Banks (The Hunger Games), who inadvertently becomes miniature due to her scientist husband's actions, portrayed by Mat…

Laurence Fishburne is set to be a part of Mike Flanagan's The Exorcist.

Mike Flanagan's upcoming remake of The Exorcist has added another notable actor to its cast. According to Variety, Laurence Fishburne, known for his roles in The Matrix and John Wick, will be joining Scarlet J...

Laurence Fishburne is set to be a part of Mike Flanagan's The Exorcist.

Mike Flanagan's upcoming remake of The Exorcist has added another notable actor to its cast. According to Variety, Laurence Fishburne, known for his roles in The Matrix and John Wick, will be joining Scarlet J...

New trailer released for Ready or Not 2: Here I Come, featuring Samara Weaving and Kathryn Newton.

Searchlight Pictures has released a new poster and trailer for the horror comedy sequel Ready or Not 2: Here I Come, directed by Tyler Gillett and Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, in anticipation of its theatrical debut this…

New trailer released for Ready or Not 2: Here I Come, featuring Samara Weaving and Kathryn Newton.

Searchlight Pictures has released a new poster and trailer for the horror comedy sequel Ready or Not 2: Here I Come, directed by Tyler Gillett and Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, in anticipation of its theatrical debut this…

From Movies to Slots: The Transformation of Popular Films into Slot Machine Themes - MovieMaker Magazine

Movie-themed slot games transform well-known posters into interactive screens, designed to provide you with a glimpse of the film in just a few quick spins, integrating

From Movies to Slots: The Transformation of Popular Films into Slot Machine Themes - MovieMaker Magazine

Movie-themed slot games transform well-known posters into interactive screens, designed to provide you with a glimpse of the film in just a few quick spins, integrating

Rotterdam Review: Tycoon is an Impressive Depiction of a City in Flames.

In a fleeting moment of Charlotte Zhang’s Tycoon, a young man mentions that he ceased his complaints to his landlord regarding the cockroaches infesting his L.A. apartment, fearing that it might lead to the entire building being condemned—a fate that has befallen many others across the city, ultimately sealed off and turned over to greedy property developers. Tycoon takes place in the future: