Sundance Review: Ira Sachs' Peter Hujar's Day Merges Documentary and Performance to Reflect on the Artist's Life

When I observe Peter Hujar’s portrait of poet Allen Ginsberg, taken on December 18, 1974, it exudes a striking sense of casualness. Ginsberg stands on the sidewalk, one hand in his pocket and the other looped through the straps of a bag resting on his shoulder. He gazes directly into the lens, wearing an expression that seems to say, “Okay, you’re taking my picture.” Although Ginsberg is arguably the most notable figure from the beat generation of poets, he appears as if he could be anyone––maybe your friend Carl. The photograph was commissioned by the New York Times, yet it lacks the polish and glamour found in contemporary celebrity portraits seen in major publications. The stark street beside him is situated in the Lower East Side, a neighborhood now overrun with tourists, trendy shops, and mediocrity. Just as Hujar’s photo reflects an artistic renaissance in New York City, so does Ira Sachs’ film, Peter Hujar’s Day.

In 1974, writer Linda Rosenkrantz initiated a project asking her artist friends to describe, in detail, what they did throughout an entire day, as she felt “I don’t do much of anything.” These discussions were recorded for a book that never materialized. Although the tapes were lost, a transcript of Rosenkrantz’s conversation with Hujar was discovered at the Morgan Library, leading to the publication of a book with the same title as Sachs’ film in 2021. The director started planning an adaptation with Ben Whishaw during the filming of his prior feature, Passages.

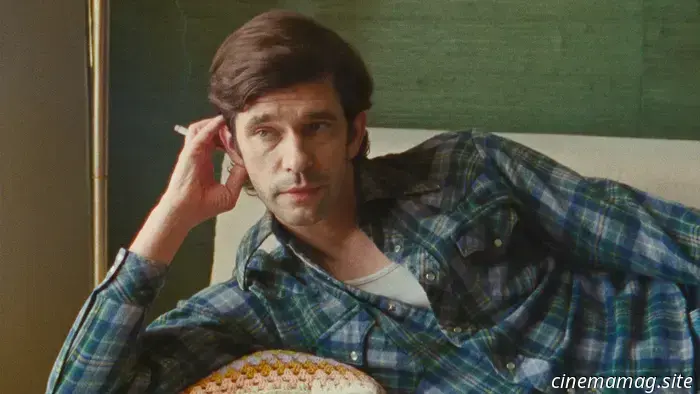

To clarify, the 76-minute duration of Peter Hujar’s Day consists primarily of a dialogue between two individuals set mostly in an apartment. While this may seem restrictive, Sachs skillfully keeps the visual dynamic without distracting from the captivating performances of Whishaw as Peter Hujar and Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz. The film results in an intimate portrayal of a queer artist’s life from a bygone era of creative energy.

A full day unfolds in Linda’s apartment as Peter recounts his previous day, from the moment he wakes up, through his two naps, to when he finally goes to sleep. He details what he ate (more liverwurst sandwiches than one might expect), the projects he engaged in, and his numerous phone calls and interactions with notable figures of the time, alongside observations of various individuals on the street that pique his curiosity––all while chain-smoking.

Their conversation transitions from room to room, with Peter and Linda growing physically closer as the day progresses. Whishaw delivers a remarkably natural performance, conveying the 55 pages of dialogue as though he is recalling his own past. Although Hall has fewer lines, her ability to portray active listening is commendable, reflected in her bright-eyed intrigue. They frequently shift positions and locations, avoiding the visual monotony that can be found in My Dinner with Andre, another film centered on conversation. Sachs frames the two much like a still-life portrait. He intersperses the dialogue with montages and a lively rockabilly dance break that serve as refreshing interludes.

The performances by Whishaw and Hall, along with the meticulous costuming, set design, and square aspect ratio, contribute to Sachs’ effective portrayal of realism. The absence of rehearsal for the two actors results in an authentic spontaneity––Peter Hujar’s Day captures the essence of a casual conversation between friends in 1974.

The frequency of phone calls received by Peter serves as a reminder of how differently we communicate today. His phone rang approximately as often as one receives a text message in modern times. I reflected on how much more pleasant it was to answer a call and hear a friend’s voice. Unlike me, however, the individuals on the other end of the line included Susan Sontag, Glenn O’Brien, Fran Liebowitz, and Allen Ginsberg, whom he met that day to take the portrait mentioned earlier. There’s no sense of name-dropping; these figures are his contemporaries, friends, and fellow bohemians who thrived in a community that once fostered originality in lower Manhattan.

His accounts do reveal a focus on the ordinary, such as when he explains watering his plants with a coffee pot filled in the tub because it’s quicker. Yet, there’s a nostalgic charm in his recollection of remembering to carry a penny because cigarettes cost 56 cents. Peter shares with Linda about the Chinese food he picked up that evening, including someone else’s order (chicken chow mein) and its price ($3.45).

These mundane anecdotes reflect Peter’s humanity, both as an artist and an individual. He candidly discusses his financial needs and the presentation of his work. They also create a dynamic range when he mentions a musician concocted by a record label as a publicity gimmick named Topaz Caucasian.

Sachs’ films often delve into the artistic process (such as

Other articles

Sundance Review: Eva Victor’s First Film Sorry, Baby is a Unique Revelation

Agnes (Eva Victor) leads a life characterized by a feeling of being stuck. Four years after finishing graduate school in rural New England, she remains in the same house and continues to go to the same place, now as a professor. The only moments of genuine happiness she encounters are the occasional visits from her best friend and former roommate.

Sundance Review: Eva Victor’s First Film Sorry, Baby is a Unique Revelation

Agnes (Eva Victor) leads a life characterized by a feeling of being stuck. Four years after finishing graduate school in rural New England, she remains in the same house and continues to go to the same place, now as a professor. The only moments of genuine happiness she encounters are the occasional visits from her best friend and former roommate.

Sniper Elite: Resistance launches on PC and consoles.

Rebellion has unveiled the launch of Sniper Elite: Resistance, the newest installment in the Sniper Elite series. This title is available in both physical and digital formats and centers around Harry Hawker, with events that occur alongside those of Sniper Elite 5. Check out the new launch trailer below…. Sniper Elite: Resistance allows players to step into the role […]

Sniper Elite: Resistance launches on PC and consoles.

Rebellion has unveiled the launch of Sniper Elite: Resistance, the newest installment in the Sniper Elite series. This title is available in both physical and digital formats and centers around Harry Hawker, with events that occur alongside those of Sniper Elite 5. Check out the new launch trailer below…. Sniper Elite: Resistance allows players to step into the role […]

How Production Designer Judy Becker Achieved a Brutalist Aesthetic on a Budget

Even prior to meeting the Brutalist director Brady Corbett, production designer Judy Becker privately wished for the opportunity to collaborate with him.

How Production Designer Judy Becker Achieved a Brutalist Aesthetic on a Budget

Even prior to meeting the Brutalist director Brady Corbett, production designer Judy Becker privately wished for the opportunity to collaborate with him.

Take a look behind the scenes of The Old Guard 2 with a sneak peek from Netflix.

Netflix has unveiled a sneak peek featurette for The Old Guard 2, providing a behind-the-scenes glimpse at the action thriller sequel. Take a look below… Directed by Victoria Mahoney, the follow-up to the 2020 comic book adaptation features the return of Charlize Theron, KiKi Layne, Matthias Schoenaerts, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Marwan Kenzari, Luca […]

Take a look behind the scenes of The Old Guard 2 with a sneak peek from Netflix.

Netflix has unveiled a sneak peek featurette for The Old Guard 2, providing a behind-the-scenes glimpse at the action thriller sequel. Take a look below… Directed by Victoria Mahoney, the follow-up to the 2020 comic book adaptation features the return of Charlize Theron, KiKi Layne, Matthias Schoenaerts, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Marwan Kenzari, Luca […]

-Movie-Review.jpg) Valiant One (2025) - Film Review

Valiant One, 2025. Directed by Steve Barnett. Featuring Chase Stokes, Lana Condor, Desmin Borges, Callan Mulvey, Diana Tsoy, Daniel Jun, Jonathan Whitesell, Stephen Adekolu, Ronald Patrick Thompson, Leo Chiang, Dimitry Tsoy, Jerina Son, and Tyrone Pak. SYNOPSIS: Amid rising tensions between North and South Korea, a US helicopter makes a crash landing on the North Korean territory. Now the […]

Valiant One (2025) - Film Review

Valiant One, 2025. Directed by Steve Barnett. Featuring Chase Stokes, Lana Condor, Desmin Borges, Callan Mulvey, Diana Tsoy, Daniel Jun, Jonathan Whitesell, Stephen Adekolu, Ronald Patrick Thompson, Leo Chiang, Dimitry Tsoy, Jerina Son, and Tyrone Pak. SYNOPSIS: Amid rising tensions between North and South Korea, a US helicopter makes a crash landing on the North Korean territory. Now the […]

New trailer released for the sci-fi horror film Ash, featuring Eiza Gonzalez and Aaron Paul.

Before its world premiere at SXSW this March, a fresh trailer for the sci-fi horror film Ash has been released online. Directed by Flying Lotus, the movie features Riya (Eiza Gonzalez) who wakes up on an enigmatic planet, only to find that her entire crew has been violently killed. However, when Brion (Aaron Paul) comes to her rescue, the two...

New trailer released for the sci-fi horror film Ash, featuring Eiza Gonzalez and Aaron Paul.

Before its world premiere at SXSW this March, a fresh trailer for the sci-fi horror film Ash has been released online. Directed by Flying Lotus, the movie features Riya (Eiza Gonzalez) who wakes up on an enigmatic planet, only to find that her entire crew has been violently killed. However, when Brion (Aaron Paul) comes to her rescue, the two...

Sundance Review: Ira Sachs' Peter Hujar's Day Merges Documentary and Performance to Reflect on the Artist's Life

When I examine Peter Hujar’s portrait of poet Allen Ginsberg, captured on December 18, 1974, it presents a remarkably casual vibe. Ginsberg stands on the sidewalk, one hand in his pocket and the other slung over the straps of a bag hanging from his shoulder. He gazes directly into the lens with a relaxed expression that says, “okay,”