A Desert Review: Neo-Noir Debut Can Only Rely on Atmosphere for a Limited Time

Anything unusual, offbeat, or psychosexual tends to invoke the term "Lynchian" in reviews, descriptions, or promotional content. It has become a shorthand, ultimately simplifying more than just the work of an influential filmmaker; it represents a style that challenges conventional narrative storytelling. Something described as Lynchian is also, inherently, somewhat enchanting and elusive.

Expect that people will characterize Joshua Erkman’s feature debut, A Desert, in this way. On the surface, it meets all the criteria. The narrative focuses on middle and rural America, features an Oz-like journey, and ultimately circles back to an ending that can be described as unclear, or at worst, nonsensical.

While the ending—a bizarre collage that seeks to reframe the preceding story—will likely be the primary subject of discussion, it’s actually the least engaging aspect of Erkman’s film. Instead, it’s the split structure that creates a captivating, though at times frustrating, narrative. Initially, the film follows washed-up photographer Alex (Kai Lennox) as he traverses the flyover states, aiming to reconnect with his most commercially successful work. Leaving behind his phone and relying on strangers for guidance, he captures the rust belt with an antique camera, documenting the dilapidation of the American West, a theme that had once brought him recognition many years prior.

A chance encounter at a rundown motel with Renny (Zachary Ray Sherman) and Susie Q (Ashley B. Smith), who claim to be siblings but likely represent a pimp and prostitute duo, abruptly derails his journey. Despite objecting to their noise, Alex invites them into his room for a portrait and to socialize, which leads him to revert to the hedonistic impulses he had suppressed long ago.

While we learn what happens to Alex after he goes missing—a choice that diminishes the suspense of the story—his wife Sam (Sarah Lind) remains unaware. From this point, A Desert shifts focus to the private investigator Harold (David Yow) she hires to find him. Harold, who is washed-up in a different sense, carries a cynical perspective that colors his investigation. He feels at home in the motels and abandoned buildings that Alex romanticized through his lens, and his quest ultimately proves less engaging than the film’s other storyline. Erkman uses these two men as contrasting figures, comparing their different approaches to the world—one views the crumbling towns as mere aesthetic objects, while the other recognizes the pervasive darkness in humanity around him.

This setup is engaging, but it doesn’t make for a particularly gripping narrative. We know what happened to Alex, and the unanswered questions about why are not compelling enough. Although occasional glimpses of a dim room filled with monitors showcasing gritty pornography hint at the dark, nightmarish journey that Harold and Sam experience towards the end, it serves primarily to create an atmosphere rather than convey a coherent message.

The situation is further complicated by the foolish decisions made by both Alex and Harold throughout. While A Desert is being labeled as somewhat horror-adjacent, it’s their bewildering choices rather than the plot that seem to lean into the genre. Alex’s decision to invite Renny and Susie Q into his room, where he ends up consuming their strange liquor, is the kind of action that invites shouts from the audience. Even more perplexing is his choice to let Renny lead him further into the desert in search of more objects to photograph. Similarly, Harold’s decision to party with Susie Q—despite her entire demeanor suggesting she intends to drug him—raises eyebrows. One would expect that even a former cop as washed-up as Harold would exercise better judgment.

It’s apparent that Erkman aims to channel Lost Highway. To some degree, he successfully creates a semblance of it, relying on atmosphere, narrative hints at deeper meanings, and hazy, neon-lit visuals. However, once the stylistic elements are established, what remains is a compelling yet frustratingly ambiguous film.

A Desert is currently in limited release.

Other articles

Star Wars joins Monopoly Go!

Scopely has revealed an exciting collaboration event featuring two cherished brands with the arrival of Star Wars in Monopoly Go! This crossover event will take players on a two-month journey covering the entire Skywalker Saga and The Mandalorian. A new trailer, along with a behind-the-scenes video showcasing the development of the collaboration, can be viewed below… […]

Star Wars joins Monopoly Go!

Scopely has revealed an exciting collaboration event featuring two cherished brands with the arrival of Star Wars in Monopoly Go! This crossover event will take players on a two-month journey covering the entire Skywalker Saga and The Mandalorian. A new trailer, along with a behind-the-scenes video showcasing the development of the collaboration, can be viewed below… […]

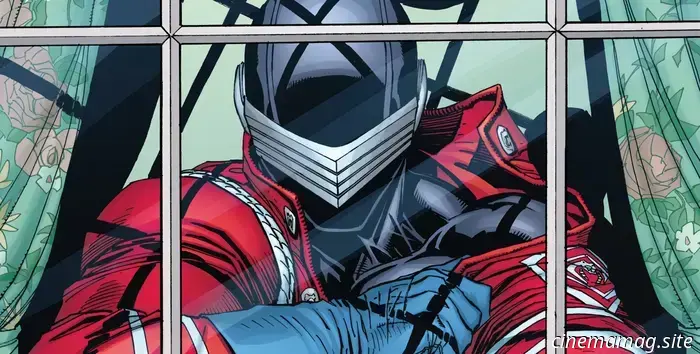

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #316 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Image and Skybound are set to release Larry Hama's G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #316 next week, and you can take an early look at the issue with the official preview below... COBRA... TRAITORS? When some members of Cobra’s elite Crimson Guard seek refuge with the Joes, it presents a chance for Snake Eyes, Scarlett, and their [...]

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #316 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Image and Skybound are set to release Larry Hama's G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #316 next week, and you can take an early look at the issue with the official preview below... COBRA... TRAITORS? When some members of Cobra’s elite Crimson Guard seek refuge with the Joes, it presents a chance for Snake Eyes, Scarlett, and their [...]

Funko has unveiled Pop! Vinyl figures based on Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds and Rear Window.

Funko has revealed that two classic Alfred Hitchcock films will soon be transformed into Pop! figures, featuring Tippi Hedren’s character Melanie Daniels from The Birds and James Stewart’s character Jeff Jefferies from Rear Window. Take a look at them here… A group is forming, and POP! Melanie Daniels is seeking shelter in […]

Funko has unveiled Pop! Vinyl figures based on Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds and Rear Window.

Funko has revealed that two classic Alfred Hitchcock films will soon be transformed into Pop! figures, featuring Tippi Hedren’s character Melanie Daniels from The Birds and James Stewart’s character Jeff Jefferies from Rear Window. Take a look at them here… A group is forming, and POP! Melanie Daniels is seeking shelter in […]

Get your first glimpse of Darren Aronofsky's Caught Stealing, featuring Austin Butler, Zoe Kravitz, and Matt Smith.

Sony Pictures has released a set of first-look images from Caught Stealing, the forthcoming adaptation of Charlie Huston’s novel, directed by Darren Aronofsky. This crime thriller boasts a cast that features Austin Butler, Matt Smith, Zoë Kravitz, Regina King, Vincent D’Onofrio, Bad Bunny, Will Brill, Griffin Dunne, D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai, Action Bronson, George Abud, and others.

Get your first glimpse of Darren Aronofsky's Caught Stealing, featuring Austin Butler, Zoe Kravitz, and Matt Smith.

Sony Pictures has released a set of first-look images from Caught Stealing, the forthcoming adaptation of Charlie Huston’s novel, directed by Darren Aronofsky. This crime thriller boasts a cast that features Austin Butler, Matt Smith, Zoë Kravitz, Regina King, Vincent D’Onofrio, Bad Bunny, Will Brill, Griffin Dunne, D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai, Action Bronson, George Abud, and others.

WWE's Liv Morgan teams up with Lily James and Shun Oguri in Takashi Miike's Bad Lieutenant: Tokyo.

Takashi Miike is currently experiencing a surge of activity, partnering with some of the most prominent figures in pop culture. The legendary and provocative Japanese director is collaborating with pop sensation Charli XCX, and he has also committed to Bad Lieutenant: Tokyo with Neon. Additionally, he is gathering an eclectic cast for this project, [...]

WWE's Liv Morgan teams up with Lily James and Shun Oguri in Takashi Miike's Bad Lieutenant: Tokyo.

Takashi Miike is currently experiencing a surge of activity, partnering with some of the most prominent figures in pop culture. The legendary and provocative Japanese director is collaborating with pop sensation Charli XCX, and he has also committed to Bad Lieutenant: Tokyo with Neon. Additionally, he is gathering an eclectic cast for this project, [...]

Sally Trailer: Sundance Award Winner Portrays the Life of a Trailblazing Astronaut

Cristina Costantini's film Sally, which won the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Feature Film Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, portrays the life of Sally Ride, the first American woman in space, along with the challenges she faced in both her public and private life. It is scheduled to premiere on National Geographic on June 16.

Sally Trailer: Sundance Award Winner Portrays the Life of a Trailblazing Astronaut

Cristina Costantini's film Sally, which won the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Feature Film Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, portrays the life of Sally Ride, the first American woman in space, along with the challenges she faced in both her public and private life. It is scheduled to premiere on National Geographic on June 16.

A Desert Review: Neo-Noir Debut Can Only Rely on Atmosphere for a Limited Time

Anything unusual, eccentric, or psychosexual tends to prompt the term "Lynchian" in descriptions, reviews, or promotional content. It has turned into a shorthand and ultimately a simplification—not just of a significant filmmaker, but of a style that challenges conventional narrative storytelling. To be Lynchian also implies a certain allure and an elusive quality.