Cannes Review: Sergei Loznitsa’s Two Prosecutors Resonates Unsettlingly with Our Post-Truth Era

When Donbass premiered in 2018, nestled between the onset of the Russian-backed conflict in the eastern Ukrainian region in 2014 and the full-scale invasion four years later, the world that Sergei Loznitsa focused his lens on was a surreal, deteriorating wasteland. The film wasn’t strictly prophetic regarding the atrocities that would subsequently engulf Ukraine; instead, it highlighted concerns that now resonate deeply, long central to the Belarus-born, Kiev-raised director’s work. Although Donbass is a fictional narrative, its exploration of truth manipulation also haunts Loznitsa's well-known archive-based documentaries. From Blockade (2006) to The Kiev Trial (2022), the director hasn’t used Soviet-era footage merely as a time machine but as a method to reclaim history from the regime’s official narratives. Thus, to label Two Prosecutors as the filmmaker’s “return to fiction,” as the Cannes Film Festival did when introducing Loznitsa’s latest into its Official Competition, is both accurate and somewhat misleading.

Inspired by a 1969 novella by Georgy Demidov, a Soviet physicist who endured 18 years in a Siberian labor camp after being convicted of Trotskyism in the late 1930s, Two Prosecutors fundamentally poses questions about truth: who controls it, and what cost is required to question it. It is reminiscent of Costa-Gavras’s political assassination thriller Z, which follows a magistrate who turns against the fascist dictatorship he ostensibly served in an unrelenting quest for justice for the murder conspirators. Fresh from university, dressed in a dark suit and coat, Kornyev (Aleksandr Kuznetsov) shares Jean-Louis Trintignant’s grim wardrobe and steadfast belief in the sanctity of facts––not considering that by 1937, when Two Prosecutors begins, the "Bolshevik Truth" to which he clings has already morphed into Stalin’s variant. The terror unleashed by the autocrat early in his regime has reached its peak, with the secret NKVD police functioning as a parallel state, persecuting innocent civilians, and replacing “honorable experts” with a host of corrupted, incompetent frauds.

So far, so relevant to 2025. Indeed, Two Prosecutors illustrates a notable aspect of Loznitsa’s explorations of the past: rather than mere artifacts from bygone eras, these works are genealogical, prompting us to reflect on the legacy of those horrors in today’s context. A few years ago, the director stated that the aim of his archival documentaries was “to portray the past as if it were the present,” making history so tangible that it feels like one can “touch it with their skin.” This is how Two Prosecutors operates, functioning as a period piece that eerily resonates with the anxieties of our 21st-century, post-truth world. Called to a prison by an inmate who somehow managed to smuggle a plea for help from behind bars, Kornyev soon realizes the NKVD has gone rogue, torturing individuals into confessing to crimes they have never committed. Convinced that his superiors will seek to restore justice, he travels to Moscow to seek help from the Attorney General.

If Z served as agitprop, Two Prosecutors adopts a more measured, austere tone. Filmed by Loznitsa’s regular cinematographer Oleg Mutu in static shots and a muted, wintry palette, the film unfolds like a chamber drama, progressing through a series of conversations that pit Kornyev against bureaucrats determined to obstruct his investigation by any means necessary. This should, in theory, render it a far less dynamic spectacle than Donbass, whose flowing long takes transformed the frontlines into a spectacle of brutality. However, what is most unsettling (and intriguing) about Two Prosecutors is the ominous tension that builds during these shot-reverse shot exchanges. Despite its outwardly stately appearance, Loznitsa's film implies impending chaos––the audience can predict Kornyev’s fate long before he reaches Moscow, which intensifies rather than detracts from the tragedy.

Nonetheless, this is not a relentlessly punishing watch. Loznitsa frequently intersperses Kornyev’s self-destructive quest with moments that shift the film closer to black comedy. State officials laugh grotesquely at the misfortunes of political rivals; bureaucrats lose their way in their own offices, not to mention the excruciatingly long waits Kornyev endures to be called by this or that official. Having pointed to Gogol and Kafka as influences, there are scenes in Two Prosecutors that resonate with the bleak absurdism of Roy Andersson.

One way in which this film diverges from Loznitsa’s earlier works is its focus on an individual rather than the crowds and collectives that have often taken center stage. Perhaps. Kornyev’s fate mirrors that of millions; this narrative does not simply revolve around a single man but instead

Other articles

Trailer untuk film horor supernatural Indonesia, Soul Reaper, dipublikasikan.

Well Go USA has released a trailer for Soul Reaper, an Indonesian supernatural horror film directed by Sidharta Tata. The story follows Respati, a young man who is tormented by a succession of violent nightmares until he discovers that these dreams are, in fact, visions that start to become real. The […]

Trailer untuk film horor supernatural Indonesia, Soul Reaper, dipublikasikan.

Well Go USA has released a trailer for Soul Reaper, an Indonesian supernatural horror film directed by Sidharta Tata. The story follows Respati, a young man who is tormented by a succession of violent nightmares until he discovers that these dreams are, in fact, visions that start to become real. The […]

Cannes Review: Enzo is a Delicately Told Queer Coming-of-Age Story

The queer coming-of-age journey is marked by significant vulnerability, as a young individual must confront the understanding that they are evolving into someone distinct from their former selves and from those in their surroundings. Robin Campillo’s Enzo, which premiered at the Directors’ Fortnight section of Cannes, effectively captures the sensitivity of this theme and offers a correspondingly nuanced, gentle depiction of its characters.

Cannes Review: Enzo is a Delicately Told Queer Coming-of-Age Story

The queer coming-of-age journey is marked by significant vulnerability, as a young individual must confront the understanding that they are evolving into someone distinct from their former selves and from those in their surroundings. Robin Campillo’s Enzo, which premiered at the Directors’ Fortnight section of Cannes, effectively captures the sensitivity of this theme and offers a correspondingly nuanced, gentle depiction of its characters.

A sequel to Spring Breakers titled Salvation Mountain has been announced, featuring Bella Thorne and others.

Deadline has revealed that a follow-up to Harmony Korine’s 2012 cult favorite Spring Breakers is in development, with original producers Chris Hanley and Jordan Gertner coming together again for Spring Breakers: Salvation Mountain. This new film, which is a standalone entry, will be directed by Matthew Bright (Freeway) and will feature Bella Thorne (The [...]).

A sequel to Spring Breakers titled Salvation Mountain has been announced, featuring Bella Thorne and others.

Deadline has revealed that a follow-up to Harmony Korine’s 2012 cult favorite Spring Breakers is in development, with original producers Chris Hanley and Jordan Gertner coming together again for Spring Breakers: Salvation Mountain. This new film, which is a standalone entry, will be directed by Matthew Bright (Freeway) and will feature Bella Thorne (The [...]).

Parasol Superstars is set to release retro classics for consoles this September.

ININ Games is set to create a wave of nostalgia and cuteness this September with the digital release of Parasol Superstars for Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, and Xbox, along with a physical version for Nintendo Switch and PS5. Parasol Superstars will include the well-loved Parasol Stars and the newly introduced retro-inspired platformer Spica Adventure.

Parasol Superstars is set to release retro classics for consoles this September.

ININ Games is set to create a wave of nostalgia and cuteness this September with the digital release of Parasol Superstars for Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, and Xbox, along with a physical version for Nintendo Switch and PS5. Parasol Superstars will include the well-loved Parasol Stars and the newly introduced retro-inspired platformer Spica Adventure.

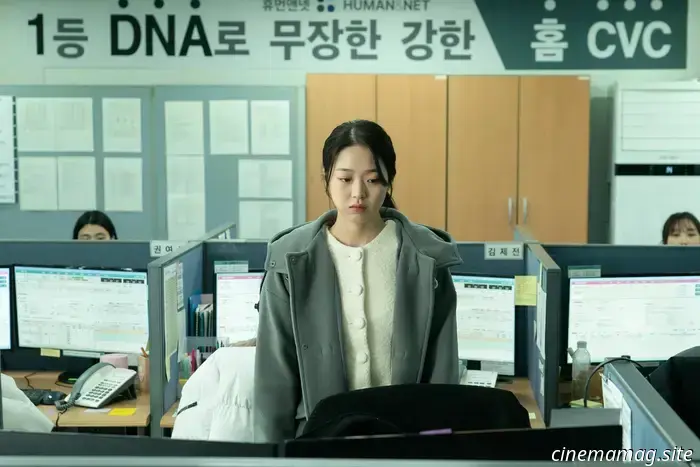

Next Sohee Review: Korean Thriller Approaches a Serious Topic with a Steady Touch

Note: This review was initially published as part of our coverage of the 2022 Fantasia festival. Next Sohee will be released in theaters on May 16. I used to think that capitalism's grip on the American education system through unpaid internships was problematic. However, as portrayed in July Jung's external drama Next Sohee, the situation in South Korea is even more concerning.

Next Sohee Review: Korean Thriller Approaches a Serious Topic with a Steady Touch

Note: This review was initially published as part of our coverage of the 2022 Fantasia festival. Next Sohee will be released in theaters on May 16. I used to think that capitalism's grip on the American education system through unpaid internships was problematic. However, as portrayed in July Jung's external drama Next Sohee, the situation in South Korea is even more concerning.

Sideshow and the Sly Stallone Shop have revealed the sixth scale figure of Rocky "The Underdog."

Sideshow and the Sly Stallone Shop have released the sixth scale Rocky (Underdog) collectible figure, capturing the likeness of Sylvester Stallone from the iconic 1976 boxing film. Take a look at both the Deluxe Edition and the Ultimate Edition here… Presenting the ROCKY “Underdog” Sixth Scale Figure, officially endorsed and approved by Sylvester Stallone himself […]

Sideshow and the Sly Stallone Shop have revealed the sixth scale figure of Rocky "The Underdog."

Sideshow and the Sly Stallone Shop have released the sixth scale Rocky (Underdog) collectible figure, capturing the likeness of Sylvester Stallone from the iconic 1976 boxing film. Take a look at both the Deluxe Edition and the Ultimate Edition here… Presenting the ROCKY “Underdog” Sixth Scale Figure, officially endorsed and approved by Sylvester Stallone himself […]

Cannes Review: Sergei Loznitsa’s Two Prosecutors Resonates Unsettlingly with Our Post-Truth Era

When Donbass was released in 2018, positioned between the onset of the 2014 Russian-backed conflict in the eponymous eastern Ukrainian area and the full-scale invasion of the country four years later, the reality Sergei Loznitsa captured with his camera was a surreal and decaying landscape. The film wasn’t exactly prescient regarding the horrors that would unfold.