Care and Consent: Navigating Ethical Filmmaking in Disability by the Life After Team

Reid Davenport serves as the director, while Colleen Cassingham is the producer of Life After, an investigative documentary addressing the ethical challenges and profit incentives surrounding assisted dying. The film, which had its premiere at Sundance, is set to be released on Friday at the Film Forum in New York, with further screenings planned nationwide. In this article, Davenport and Cassingham discuss how Multitude Films, where Cassingham is employed, brought in a clinical psychiatrist to support and safeguard participants in the documentary.—M.M.

Our documentary Life After reveals how systemic failures such as poverty, lack of healthcare access, and histories of institutionalization and eugenics restrict the autonomy of disabled individuals. The film amplifies the voices of the disability community in the ongoing discussion about assisted dying, exposing distressing accounts of disabled people facing premature death — and questioning the notion that assisted dying is always a free choice, as it can at times appear to be the only alternative.

Due to the sensitive nature of the subject and the vulnerability of our participants, it was crucial for our team to ensure that we approached each phase of the filmmaking process with care and integrity.

The dynamics between filmmakers and participants are complex — they are personal, professional, and something in between. We rely on intuition and good intentions, yet we lack a clearly defined framework and guiding principles to reduce harm and prioritize care. In creating Life After, we chose to invite inherently vulnerable individuals to participate, which instilled in us a profound sense of responsibility towards them.

Life After and Documentary Ethics

To shape our approach, we collaborated with clinical psychiatrist Dr. Kameelah Oseguera (“Dr. Kam”), who leads care at Multitude Films. Dr. Kam is committed to implementing our team’s dedication to care and is an expert in trauma-informed practices within documentary filmmaking. Her role supports both the film crew and participants in navigating ethical dilemmas and challenges that can arise during nonfiction filmmaking, along with their potential impacts on all involved.

During production, Dr. Kam assisted us in conducting emotionally charged interviews with sensitivity, clarity, and attentiveness to our participants' needs and concerns. One perspective we aimed to incorporate in Life After was that of a Canadian individual with a disability or chronic illness who considered Canada's Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) in light of poverty or healthcare and housing access issues.

Also Read: Fighting, Making Friends at Camp, and Selling Cookies Are Topics of NFMLA’s Disabilities Program

Recognizing the risks associated with engaging with these individuals, we established an internal rubric to evaluate who we could approach safely, adhering to our guiding principle of "do no harm." We considered factors such as prior media engagement, the stage of their MAID application, their health and financial situations, and their external support systems.

In selecting participants, Dr. Kam acted as a third-party liaison, providing care sessions before and after interviews to help them process their involvement, as well as ongoing support throughout the film's launch and rollout.

Throughout our collaboration with Dr. Kam, she emphasized that ethical storytelling goes beyond safeguarding others; it also involves equipping ourselves with foresight, confidence, and integrity. This experience taught us that the trauma carried by particularly vulnerable participants can challenge the creation of a mutually respectful and meaningful production.

To counter this, we intentionally fostered a working environment focused on patience, empathy, and accommodation, without being overbearing. Establishing a degree of partnership with our participants was essential for managing conflict in constructive ways.

As documentary filmmakers, we must acknowledge our accountability toward our participants. However, Dr. Kam helped us recognize that this responsibility needs to have boundaries — it should not be all-consuming. These boundaries may vary for each filmmaker, project, and participant. For us, it involved ensuring that the responsibility of care did not lead to "role strain" solely on the producer and being transparent with participants about how communication frequency would change during different project stages.

We also set the expectation that the film team would maintain creative autonomy and provided clear, defined opportunities for participants to offer feedback on and reaffirm their consent regarding our representation of their stories.

Ethical filmmaking improves through experience. We may not have executed these principles perfectly every time, but Life After enhanced our ability to prioritize care and integrity at all levels. The significance of a strong film team in fostering a successful environment for both filmmakers and participants is profound, and Dr. Kam's professional guidance made a significant difference in Life After.

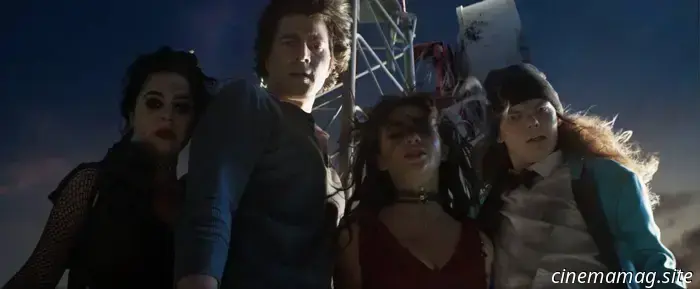

Main image: Life After director Reid Davenport and producer Colleen Cassingham. Courtesy of Multitude Films

Other articles

The trailer and poster for Jay Duplass' romantic comedy The Baltimorons, set on Christmas Eve, have been released.

Following its world premiere earlier this year at SXSW, IFC Films has unveiled a poster and trailer for the new comedy The Baltimorons, directed by Jay Duplass. Michael Strassner plays Cliff, a recovering alcoholic facing a dental emergency who forms an unexpected bond with his practical dentist Didi (Liz Larsen), resulting in the pair […]

The trailer and poster for Jay Duplass' romantic comedy The Baltimorons, set on Christmas Eve, have been released.

Following its world premiere earlier this year at SXSW, IFC Films has unveiled a poster and trailer for the new comedy The Baltimorons, directed by Jay Duplass. Michael Strassner plays Cliff, a recovering alcoholic facing a dental emergency who forms an unexpected bond with his practical dentist Didi (Liz Larsen), resulting in the pair […]

Ick Review: Joseph Kahn’s Hilarious and Satirical Perspective on the Monster Movie Genre

Note: This review was initially published in our coverage of Cannes 2025. Ick will be released in theaters on July 24. In Ick, Joseph Kahn's newest genre film following 2017's Bodied and 2011's Detention, the world is coming to an end and no one seems to care. Although Kahn has directed just four films over the past two decades, he remains a prominent figure in pop culture.

Ick Review: Joseph Kahn’s Hilarious and Satirical Perspective on the Monster Movie Genre

Note: This review was initially published in our coverage of Cannes 2025. Ick will be released in theaters on July 24. In Ick, Joseph Kahn's newest genre film following 2017's Bodied and 2011's Detention, the world is coming to an end and no one seems to care. Although Kahn has directed just four films over the past two decades, he remains a prominent figure in pop culture.

Venice Film Festival Reveals 2025 Program

Marking its 82nd edition this year, the Venice Film Festival is scheduled to run from August 27 to September 6. In anticipation of the event, President Pietrangelo Buttafuoco and Director Alberto Barbera have revealed the lineup. Notable films include works from Jim Jarmusch, Park Chan-wook, Lucrecia Martel, Laura Poitras, Benny Safdie, Werner Herzog, Kathryn Bigelow, and Luca Guadagnino.

Venice Film Festival Reveals 2025 Program

Marking its 82nd edition this year, the Venice Film Festival is scheduled to run from August 27 to September 6. In anticipation of the event, President Pietrangelo Buttafuoco and Director Alberto Barbera have revealed the lineup. Notable films include works from Jim Jarmusch, Park Chan-wook, Lucrecia Martel, Laura Poitras, Benny Safdie, Werner Herzog, Kathryn Bigelow, and Luca Guadagnino.

-collectible-statue-officially-revealed.jpg) McFarlane Toys has officially unveiled their DC Direct Joker (Purple Craze) collectible statue.

McFarlane Toys has introduced the limited edition tenth scale DC Direct Joker (Purple Craze) statue, inspired by the cover art of artist Ed McGuinness. It is currently available for pre-order at a price of $149.99; you can take a look at it here…. In a surprising turn of events, Batman’s arch-enemy, The Joker, has gained the ability to alter reality to fit his own chaotic desires […]

McFarlane Toys has officially unveiled their DC Direct Joker (Purple Craze) collectible statue.

McFarlane Toys has introduced the limited edition tenth scale DC Direct Joker (Purple Craze) statue, inspired by the cover art of artist Ed McGuinness. It is currently available for pre-order at a price of $149.99; you can take a look at it here…. In a surprising turn of events, Batman’s arch-enemy, The Joker, has gained the ability to alter reality to fit his own chaotic desires […]

12 Sleazy Movies from the 1970s That Don't Value Your Respect

These films from the 1970s are unapologetically lowbrow. The '70s were an outstanding decade for cinema as a whole, but they particularly shone in producing sleazy films.

12 Sleazy Movies from the 1970s That Don't Value Your Respect

These films from the 1970s are unapologetically lowbrow. The '70s were an outstanding decade for cinema as a whole, but they particularly shone in producing sleazy films.

Care and Consent: Navigating Ethical Filmmaking in Disability by the Life After Team

Reid Davenport serves as the director, while Colleen Cassingham is the producer of Life After, an investigative documentary focused on moral dilemmas and profit-driven motives.