Diciannove Review: Giovanni Tortorici's First Feature is Stylish but Lacks Substance.

Luca Guadagnino, whether positively or negatively, serves as a key figure and cultural marker of taste. Following his direction guarantees a sensory experience, although one that often remains superficial. Since the release of Call Me By Your Name, Guadagnino has supported emerging filmmakers whose works are both visually appealing and intellectually intriguing. This includes Italian director Ferdinando Cito Filomarino (Antonia, Beckett) and, more prominently, Georgian director Dea Kulumbegashvili (April). Last year, Giovanni Tortorici, who previously assisted Guadagnino on the HBO series We Are Who We Are, added his name to this group when his film Diciannove debuted in the Orizzonti section of the Venice Film Festival, receiving positive reviews from critics. This semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story centers on a repressed homosexual intellectual in Tuscany. Color me intrigued.

Much like Leonardo, the 19-year-old main character portrayed by Manfredi Marini, Diciannove embodies a restless inertia. At the beginning of the film, set in Palermo in 2015, Leonardo is preparing to move to London to live with his sister Arianna (Vittoria Planeta) and pursue economics. However, after a few weeks experiencing the city’s lively nightlife and feeling out of place, he relocates to Siena to spend his days sequestered in a rundown room reading Daniello Bartoli and readying himself for debates with his literature instructors. Over the span of a year, we witness Leonardo’s growth as he solidifies his moral beliefs while navigating the limits of his understanding of the world.

What stands out in Diciannove, aside from its somewhat conventional premise, is its distinct style. With the assistance of cinematographer Massimiliano Kuveiller and Guadagnino’s go-to editor Marco Costa, Tortorici enhances the film with various stylistic choices, including sudden slow-motion sequences, pseudo-surreal montages, abrupt zooms, fade-outs, freeze-frames, and poorly executed animation. Frequently, these techniques symbolize shifts in Leonardo’s mental state, particularly during his quiet exploration of his sexuality. Whether on a train, catching a glimpse of a man across from him engaging in self-pleasure, or navigating his fixation on a local underage teen, the form of Diciannove mirrors his arousal and excitement, amplified by David Tarantino’s captivating musical selections.

However, the key distinction between Tortorici and Guadagnino (as well as Xavier Dolan, Sofia Coppola, and Wong Kar-wai before them) is that their films maintained engagement beyond mere fanciful flights; they featured strong narratives with stakes that effectively benefited from intermittent stylistic enhancements. Leonardo, by design, simply drifts—attending parties, pursuing desire, and immersing himself in literature—but it culminates in a lack of interest or tension. Diciannove maintains a languid, summery atmosphere while aching for meaningful consequences. There’s a suggestion that some narrative threads in life—like Leonardo’s nosebleed—lead nowhere, which is indeed part of being nineteen. Nevertheless, Tortorici doesn’t develop this theme further; it merely serves as a time capsule for this self-centered, unlikable character’s developmental phase, resulting in a stylish yet superficial depiction of narcissism.

“Beware of fanaticism, which can lead to foolishness and distortion,” states Italian philosopher Sergio Benvenuto in a cameo towards the film's conclusion. “Be cautious, for your individual situation does not represent a universal case… in short, you are a poor wretch.” Leonardo hangs his head in contemplation, seemingly processing the critique, but as he leaves home and strolls through the streets at night with a smug grin, it’s clear he has no intention of changing. Benvenuto becomes yet another figure of authority to defy.

Diciannove will be released in theaters on Friday, July 25.

Other articles

Smith and Sullivan from Doctor Who are brought together again for new audio adventures.

Big Finish Productions has launched "Smith and Sullivan: Reunited," a fresh full-cast audio drama featuring two former companions from Doctor Who. This new box set presents exciting new escapades for investigative journalist Sarah Jane Smith and freelance UNIT operative Harry Sullivan. Sarah Jane Smith and Harry Sullivan previously journeyed through time and space alongside the Doctor; now […]

Smith and Sullivan from Doctor Who are brought together again for new audio adventures.

Big Finish Productions has launched "Smith and Sullivan: Reunited," a fresh full-cast audio drama featuring two former companions from Doctor Who. This new box set presents exciting new escapades for investigative journalist Sarah Jane Smith and freelance UNIT operative Harry Sullivan. Sarah Jane Smith and Harry Sullivan previously journeyed through time and space alongside the Doctor; now […]

Into the Dead: Our Darkest Days receives a significant new update.

PikPok Games has released the second significant update for their zombie shelter survival title, Into the Dead: Our Darkest Days. This new update introduces a wealth of additional content to the early access game, presenting further challenges for survivors in this post-apocalyptic environment. A new trailer highlighting the updates can be viewed below…. Surviving in the zombie-ravaged ruins of […]

Into the Dead: Our Darkest Days receives a significant new update.

PikPok Games has released the second significant update for their zombie shelter survival title, Into the Dead: Our Darkest Days. This new update introduces a wealth of additional content to the early access game, presenting further challenges for survivors in this post-apocalyptic environment. A new trailer highlighting the updates can be viewed below…. Surviving in the zombie-ravaged ruins of […]

Michael Jai White is being pursued in the trailer for the hitman action thriller Hostile Takeover.

Quiver Distribution has released a trailer, poster, and promotional images for Hostile Takeover, the forthcoming action thriller directed by Michael Hamilton-Wright. Michael Jai White takes on the role of Pete Strykyr, a top hitman who inadvertently becomes a target after he joins a support group for workaholics. Watch the trailer below… Pete Strykyr is […]

Michael Jai White is being pursued in the trailer for the hitman action thriller Hostile Takeover.

Quiver Distribution has released a trailer, poster, and promotional images for Hostile Takeover, the forthcoming action thriller directed by Michael Hamilton-Wright. Michael Jai White takes on the role of Pete Strykyr, a top hitman who inadvertently becomes a target after he joins a support group for workaholics. Watch the trailer below… Pete Strykyr is […]

Fantasia Review: I Am Frankelda, Mexico's First Stop-Motion Film, Conveys Powerful Messages

Beyond the similarly mythologized Monsters, Inc., the inaugural stop-motion feature made in Mexico (from the Cinema Fantasma studio) draws memories of a beloved childhood film from the '80s: Little Monsters. Much like that Fred Savage film, the writer-director duo Los Hermanos Ambriz (Arturo and Roy) has devised a way to bridge the gap between reality and nightmare, allowing a human

Fantasia Review: I Am Frankelda, Mexico's First Stop-Motion Film, Conveys Powerful Messages

Beyond the similarly mythologized Monsters, Inc., the inaugural stop-motion feature made in Mexico (from the Cinema Fantasma studio) draws memories of a beloved childhood film from the '80s: Little Monsters. Much like that Fred Savage film, the writer-director duo Los Hermanos Ambriz (Arturo and Roy) has devised a way to bridge the gap between reality and nightmare, allowing a human

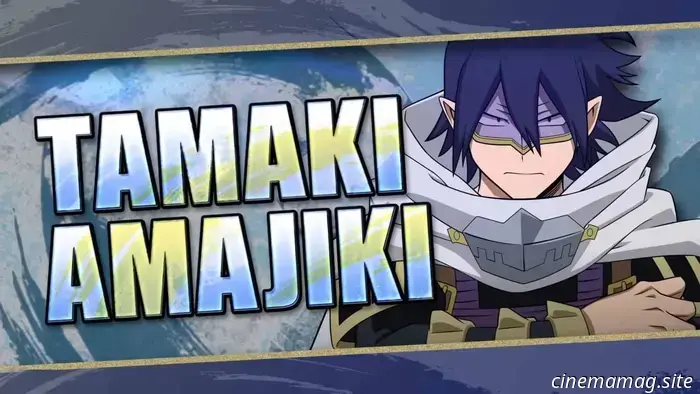

The arrival of Season 12 introduces a new character to My Hero Ultra Rumble.

Season 12 of Bandai Namco’s My Hero Ultra Rumble has launched, introducing a formidable new character, Tamaki Amajiki, one of the Big Three at U.A. High School. You can see this character in the fresh trailer provided below. Additionally, Season 12 features new outfits for several of your favorite characters and there’s […]

The arrival of Season 12 introduces a new character to My Hero Ultra Rumble.

Season 12 of Bandai Namco’s My Hero Ultra Rumble has launched, introducing a formidable new character, Tamaki Amajiki, one of the Big Three at U.A. High School. You can see this character in the fresh trailer provided below. Additionally, Season 12 features new outfits for several of your favorite characters and there’s […]

Diciannove Review: Giovanni Tortorici's First Feature is Stylish but Lacks Substance.

Luca Guadagnino, for better or worse, serves as a reference point—and cultural indicator—of taste. By following his direction, you can expect a sensory experience, though it rarely delves deeply beneath the surface. In the time since *Call Me By Your Name*, Guadagnino has supported emerging talents whose films also possess a distinct aesthetic.