Locarno Review: A Remarkable Debut, Blue Heron Explores Self and Cinema in a Unique Seance

In "Nine Behind," one of Sophy Romvari’s earliest short films, a young woman is heard crying on the phone to her estranged grandfather, saying, “I want to know my family.” This haunting line resonates throughout all of Romvari’s subsequent works. As a Canadian-born daughter of Hungarian immigrants, Romvari has consistently explored themes of fractured identities, and her films are filled with young, isolated individuals attempting to piece their identities together. Even in films that do not directly reference her heritage—such as "Grandma’s House," which overlays old photographs of her deceased grandmother with images of the woman’s flat in Budapest, "Remembrance of Józself Romvári," a tribute to her grandfather, and "Still Processing," which deals with the loss of two of her brothers—Romvari’s body of work acts as a form of personal archaeology. Blurring the lines between autobiography and fiction, her films unfold as explorations of the self and the cinematic medium. Despite their loneliness, there is a profound catharsis for both the director and the audience. This deep intimacy makes discussing her films challenging, as it often leaves words feeling inadequate and urges us to ponder what can be expressed and what remains concealed, which is frequently a theme across her oeuvre.

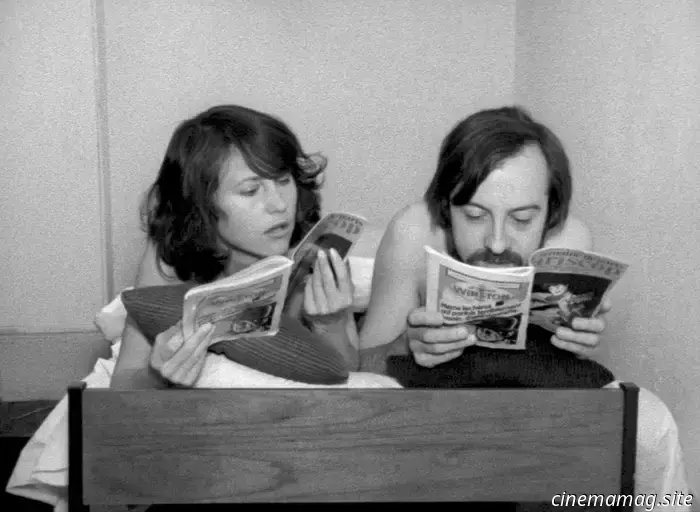

"Blue Heron," Romvari’s feature debut, once more draws from her personal history, telling the story of a Hungarian family of six settling in an unremarkable suburban area outside Vancouver. The film opens with the line, “I struggle now to remember much of my childhood,” spoken by the youngest child, Sasha (Eylul Guven), reflecting on her older stepbrother Jeremy (Edik Beddoes), a brooding, quiet teenager with a past of self-destructive behavior that no one knows how to handle. However, Romvari does not dismiss him as merely a troubled youth. While it is clear he is struggling, he emerges as the most enigmatic, elusive character in "Blue Heron," and this complexity demonstrates Romvari’s empathy. Instead of framing his pain as a disorder—something his own parents do—she invites us to sit with his suffering, to appreciate his long silences, and to explore the spaces between words and imperfect memories that the adult Sasha (Amy Zimmer) will attempt to reconstruct in the latter part of the film.

Romvari’s works can often be interpreted as forensic examinations where a young adult—usually an emerging filmmaker—takes on the role of a detective, uncovering family secrets and grappling with the consequences of those revelations. In "Blue Heron," the visual language embodies these investigative instincts literally. Rather than extracting cheap sentiment through close-ups, Romvari and cinematographer Maya Bankovic maintain a respectful distance, allowing the camera to linger outside of windows and door frames, periodically zooming in as if trying to eavesdrop on the characters. In another director's hands, these camera movements might feel voyeuristic; in Romvari’s, they highlight Sasha’s limited perspective. Since "Blue Heron" focuses on Jeremy, it is tethered to her point of view—what she observed, what she overheard, and what she was protected from—and at times it feels as if the camera is an artifact witnessing events from the future, operated by someone intent on reviving those memories rather than merely glimpsing them.

This tension is central to Romvari’s cinema. To the uninitiated, her films may appear as vast family photo albums, yet there is nothing nostalgic or sentimental about her exploration of them. The old photographs, videos, and various audio-visual souvenirs in her work serve as veils, and in bringing them to light, Romvari attests to the impossibility of capturing something as fluid as time through the stillness of images. Sasha’s parents frequently use a camera to document fleeting moments of familial joy, but there is an underlying sadness in these efforts—an awareness that each cherished instant is bound to be lost. This does not render "Blue Heron" a mere requiem but rather emphasizes the warmth Romvari extends to these individuals and their environment. The meticulous attention she and production designer Victoria Furuya pay to recreating the 1990s setting of Sasha’s upbringing—from clothing to soundscapes, including the echoes of old Looney Tunes cartoons—does not evoke a syrupy nostalgia for a bygone era, but instead reflects a director genuinely invested in capturing its intricate textures.

It is a common assertion that a film’s universality is determined by how well it conveys specific details—that to transcend its context, a work must authentically encapsulate its settings. However, what occurs when these particulars are rooted in unspeakable, deeply personal pain? While "Blue Heron" is a fictional narrative, quite distinct from the more immediate "Still Processing," Sasha’s family acts as a proxy for Romvari’s own, and the remarkable aspect of her debut feature is the restraint with which she evokes a long-standing history of

Other articles

Space Ghost #1 - Comic Book Teaser

Dynamite Entertainment will release Space Ghost #1 on Wednesday, and we have the official preview of the issue for you below; take a look… The Guardian of the Spaceways is back to battle evil in this brand-new series, starting with the debut of a classic Space Ghost villain! As Space Ghost and Blip […]

Space Ghost #1 - Comic Book Teaser

Dynamite Entertainment will release Space Ghost #1 on Wednesday, and we have the official preview of the issue for you below; take a look… The Guardian of the Spaceways is back to battle evil in this brand-new series, starting with the debut of a classic Space Ghost villain! As Space Ghost and Blip […]

NYC Weekend Guide: Luc Moullet, Who Killed Teddy Bear?, The Lovers on the Bridge, and More

NYC Weekend Watch is our weekly summary of repertory highlights. Film at Lincoln Center kicks off a retrospective of Luc Moullet's career; screenings of In the Mood for Love and In the Mood for Love 2001 are ongoing. Museum of Modern Art starts a retrospective dedicated to Michael Caine. Film Forum will showcase the rediscovered director's cut of Joseph Cates' Who Killed Teddy Bear? on 35mm, alongside Roman Polanski's An.

NYC Weekend Guide: Luc Moullet, Who Killed Teddy Bear?, The Lovers on the Bridge, and More

NYC Weekend Watch is our weekly summary of repertory highlights. Film at Lincoln Center kicks off a retrospective of Luc Moullet's career; screenings of In the Mood for Love and In the Mood for Love 2001 are ongoing. Museum of Modern Art starts a retrospective dedicated to Michael Caine. Film Forum will showcase the rediscovered director's cut of Joseph Cates' Who Killed Teddy Bear? on 35mm, alongside Roman Polanski's An.

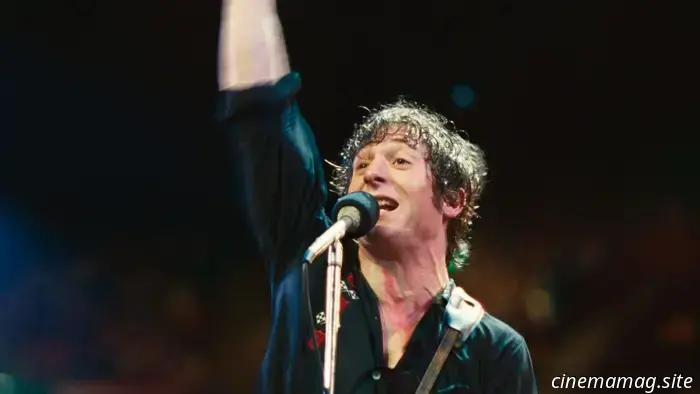

The 63rd New York Film Festival has chosen Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere as its Spotlight Gala presentation.

Following the announcement of their Main Slate and Currents selections, the 63rd New York Film Festival has now disclosed its Spotlight Gala choice: Scott Cooper’s Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere, which will premiere on Sunday, September 28. Cooper, along with cast members Jeremy Allen White, Jeremy Strong, and Odessa Young, will be present at the event.

The 63rd New York Film Festival has chosen Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere as its Spotlight Gala presentation.

Following the announcement of their Main Slate and Currents selections, the 63rd New York Film Festival has now disclosed its Spotlight Gala choice: Scott Cooper’s Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere, which will premiere on Sunday, September 28. Cooper, along with cast members Jeremy Allen White, Jeremy Strong, and Odessa Young, will be present at the event.

Locarno Review: A Remarkable Debut, Blue Heron Explores Self and Cinema in a Unique Seance

In Nine Behind, one of Sophy Romvari's early short films, a young woman can be heard weeping on the phone to her estranged grandfather, stating, "I want to know my family." This line resonates throughout all the films the director has created since then. As a Canadian-born daughter of Hungarian immigrants, Romvari has consistently explored themes of fragmented identities, and