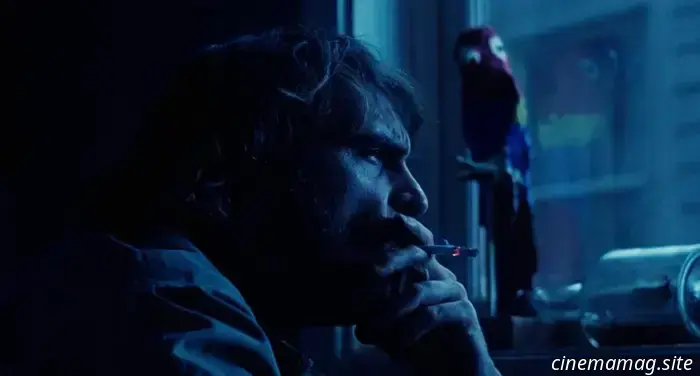

Pynchon, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Postmodernism in Cinema

Paul Thomas Anderson is making another attempt at adapting Thomas Pynchon with One Battle After Another, a contemporary reinterpretation of the reclusive author's 1990 work, Vineland. Pynchon has also made headlines recently with the release of his new novel, Shadow Ticket, which will be available in October, alongside a possible sighting of him on Getty Images.

However, critics and skeptics have beaten the film to the punch. They claim it lacks commercial appeal (even with DiCaprio attached). They argue it is too intellectual (despite featuring guns and spies). They also suggest that its reported budget of over $130 million, which exceeds the box office of all previous Anderson films, is excessive (even with premium theater screenings). In light of this speculation, it seems necessary to gather more data. As my contribution to the discussion, I've compiled an overview of Pynchon and other American Postmodern novelists' experiences in film.

Postmodernism is a complex term—it spans from Andy Warhol to Decolonial Theory to The White Album. In everyday usage, it might refer to anything avant-garde since WWII, anything pretentious from that period, or anything with leftist politics post-WWII. Here, however, it pertains to a more defined group: a select, critically lauded circle of American authors who gained renown in the 1960s. This group generally includes Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, William Gaddis, Robert Coover, John Hawkes, William H. Gass, Kurt Vonnegut, and Susan Sontag—all of whom conveniently dined together to mock the label. For my discussion, I’ve also included Don DeLillo (who became prominent in the 1980s) and Ishmael Reed (who should have attended that dinner and is notably referenced in Gravity’s Rainbow).

Artistic movements arise from historical opportunities. The critical acclaim and readership enjoyed by these authors stem from a distinct set of circumstances: the emergence of the highbrow comic novel (primarily due to the phenomenal success of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 in 1961), the significant role of literature in the counterculture (especially following Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in 1957 and William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch in 1959), the impact of continental philosophy (Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Sartre), and the literary challenges posed by modernism (Woolf, Joyce, Proust, Nabokov). In short, this was a group of highly literary countercultural authors who penned philosophically serious comic novels in the 1960s and 1970s, many of which were quite lengthy. (As is often the case, there are exceptions—John Hawkes wrote only short novels, Susan Sontag wasn't humorous, and William H. Gass had no ties to the counterculture.)

Avant-garde writing, including humorous avant-garde works, does not lend itself well to adaptation. Mainstream narrative cinema is rooted in middlebrow melodrama: books like The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind convert effectively into films, while Ulysses and Lolita result in more perplexing adaptations. With the impending Pynchon adaptation, it might be enlightening (and amusing) to examine the cinematic efforts of Pynchon’s contemporaries.

1. Duet for Cannibals (Susan Sontag, 1969)

By the time Susan Sontag attempted directing, she had already produced two novels and two essay collections, including Against Interpretation. Influenced by Bergman and Godard, she envisioned her films resembling theirs. Duet for Cannibals, shot in Swedish—a language she did not speak—was the first of four films she directed. It is an ambitious, meticulously crafted exploration of sophisticated Swedish sexual dynamics featuring poetry, potential suicide, and shaving cream, but it never gains momentum. Like Sontag’s novels, Duet for Cannibals is aesthetically pleasing but ultimately lacks life and inspiration. Sontag's failure in cinema did not encourage her literary peers; none of the authors mentioned subsequently ventured into directing.

2. End of the Road (Adam Avakian, 1970)

John Barth’s 1958 novel The End of the Road is his most straightforward and serious work—an intellectual ménage à trois with literal consequences stemming from a woman’s metaphorical pregnancy with ideas. The film adaptation, however, lacks sophistication and decorum.

Reimagined by Adam Avakian and Terry Southern (who wrote Dr. Strangelove, Easy Rider, and Barbarella) for 1970, Barth’s characters shift from disillusioned beatniks to assertive hippies. The film's opening 20 minutes are a frenetic collage reflecting modern life—the Holocaust, World War II, nuclear weapons, and numerous flashing American flags—featuring historical events like the moon landing, JFK, and

Other articles

Venice Review: François Ozon's The Stranger Truly Does Justice to Albert Camus' Novel in Film Form

Nobel Prize winner Albert Camus is among the most significant thinkers and authors in the French language, known for crafting absurdist characters and universes that present a perspective on human existence that is strikingly distinctive. His first novel, The Stranger, has been adapted into films twice since its release in 1942, first by the Italian master Luchino.

Venice Review: François Ozon's The Stranger Truly Does Justice to Albert Camus' Novel in Film Form

Nobel Prize winner Albert Camus is among the most significant thinkers and authors in the French language, known for crafting absurdist characters and universes that present a perspective on human existence that is strikingly distinctive. His first novel, The Stranger, has been adapted into films twice since its release in 1942, first by the Italian master Luchino.

Wargaming marks a decade of World of Warships with a new update.

World of Warships has been delivering naval combat experiences on the open seas for an entire decade. To mark this significant milestone, Wargaming has packed September’s update with a wealth of new content, substantial rewards, and much more. Check out the new video below to discover what update 14.8 has to offer. In recent […]

Wargaming marks a decade of World of Warships with a new update.

World of Warships has been delivering naval combat experiences on the open seas for an entire decade. To mark this significant milestone, Wargaming has packed September’s update with a wealth of new content, substantial rewards, and much more. Check out the new video below to discover what update 14.8 has to offer. In recent […]

How Succession Employs Precise Editing to Create Tension and Power Dynamics - MovieMaker Magazine

Contemporary television has transformed into an impressive realm characterized by exceptional storytelling, acting, and cinematography. These elements are all intertwined through the process of editing.

How Succession Employs Precise Editing to Create Tension and Power Dynamics - MovieMaker Magazine

Contemporary television has transformed into an impressive realm characterized by exceptional storytelling, acting, and cinematography. These elements are all intertwined through the process of editing.

In the initial teaser trailer for Robin Hood, Sean Bean portrays the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Robin Hood is making his comeback to television this November, with MGM+ presenting a fresh interpretation of the English folk hero. The streaming service has released a first-look teaser for the upcoming series, showcasing Sean Bean (Game of Thrones) in the role of the formidable Sheriff of Nottingham, alongside Connie Nielsen (Gladiator) as […]

In the initial teaser trailer for Robin Hood, Sean Bean portrays the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Robin Hood is making his comeback to television this November, with MGM+ presenting a fresh interpretation of the English folk hero. The streaming service has released a first-look teaser for the upcoming series, showcasing Sean Bean (Game of Thrones) in the role of the formidable Sheriff of Nottingham, alongside Connie Nielsen (Gladiator) as […]

10 Short Films You Can't Miss at TIFF 2025

Featuring 48 titles from 28 nations, this year's Short Cuts program at the Toronto International Film Festival shows no major difference compared to 2024 (with 48 short films but from 23 countries, indicating slightly increased geographic diversity). Divided into seven smaller segments, Short Cuts provides a concise overview of global cinema in

10 Short Films You Can't Miss at TIFF 2025

Featuring 48 titles from 28 nations, this year's Short Cuts program at the Toronto International Film Festival shows no major difference compared to 2024 (with 48 short films but from 23 countries, indicating slightly increased geographic diversity). Divided into seven smaller segments, Short Cuts provides a concise overview of global cinema in

The spinoff of The Boys, titled Gen V, has released a new teaser trailer for season 2.

With just over two weeks remaining until Gen V makes its return for its second season, a new teaser trailer has been released online for The Boys spinoff series. The second season of Gen V features the return of Jaz Sinclair as Marie Moreau, Lizze Broadway as Emma Meyer, Maddie Phillips as Cate Dunlap, London Thor as […]

The spinoff of The Boys, titled Gen V, has released a new teaser trailer for season 2.

With just over two weeks remaining until Gen V makes its return for its second season, a new teaser trailer has been released online for The Boys spinoff series. The second season of Gen V features the return of Jaz Sinclair as Marie Moreau, Lizze Broadway as Emma Meyer, Maddie Phillips as Cate Dunlap, London Thor as […]

Pynchon, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Postmodernism in Cinema

Paul Thomas Anderson is making another attempt at adapting Thomas Pynchon in One Battle After Another, a contemporary reinterpretation of the reclusive writer's 1990 book Vineland. Meanwhile, Pynchon is making headlines again with his new novel, Shadow Ticket, set to release in October (along with a possible sighting of the elusive author on Getty Images). However, the