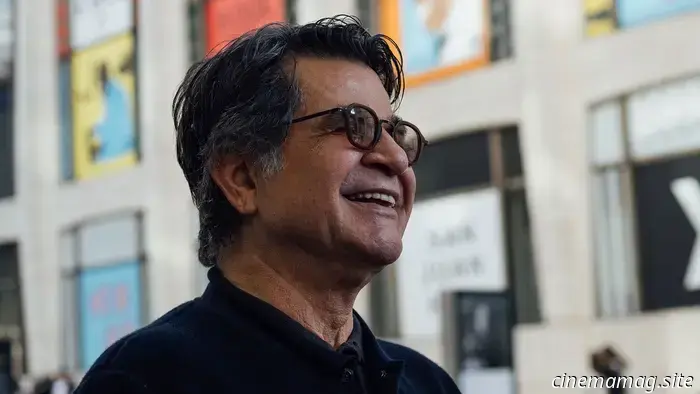

"We Must Describe Precisely What We Observe": Jafar Panahi Discusses It Was Just an Accident

Jafar Panahi arrives in the United States as both a symbol of history and a fresh beginning. His prominence as one of Iran’s foremost filmmakers is evident, particularly through his associations with Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Mohammad Rasoulof, and especially Abbas Kiarostami––more than merely directing his own scripts, he also appears as Jafar in Through the Olive Trees. However, since receiving a jail sentence and a "filmmaking ban" from the Iranian government in 2009, he has emerged as a beacon of bravery in the history of cinema, one of the rare living filmmakers who can truly be described as courageous. (He has, interestingly, declined this label, which only increases the admiration for him.)

This background has been extensively analyzed, but since Panahi has had limited opportunities to create films––despite his successes with This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, Taxi, 3 Faces, and No Bears––he’s not likely to engage in interviews about them. This makes the release of his Palme d’Or-winning film It Was Just an Accident all the more significant: we spoke in New York on the film’s press day—a concept that has long been unfamiliar to him—just before his discussion with Martin Scorsese and ahead of a cross-country Q&A tour starting with the film’s release today.

I extend my gratitude to Sheida Dayani for her on-site translation.

The Film Stage: I’ve admired your films for over a decade and have followed them with keen interest. Given the circumstances under which they were created, you haven’t conducted interviews about them. I wonder if your perspective on this film and its process has changed after talking about it for several months.

Jafar Panahi: First, I want to say those were good days when I didn’t have to discuss my film.

Sorry.

[Laughs] I made my film and had no need to speak about it. But yes, of course—in these discussions, you often uncover insights you hadn’t previously considered. You might even notice that the audience focuses on elements different from what you intended to highlight. For example, many people tell me that I aimed to create a film about forgiveness or vengeance, but I maintain that my concerns were not solely about those themes. While they are elements of the story, they serve as catalysts to keep the narrative flowing.

My actual concern was about the future of my country. I wanted to pose the question: what happens next? Will we continue with violence, or can we reach a point where we say enough is enough? As one character in the film asks, when will the cycle of violence cease?

Have you felt frustrated with the reactions to it if they haven’t aligned with your expectations?

To be honest: no. Much more has been achieved in audience reactions than I anticipated. For example, I focused a great deal on sound, and I see that it has resonated well with viewers.

Panahi with Martin Scorsese and Jim Jarmusch. Photos by Arin Sang-urai and Mettie Ostrowski, courtesy of the New York Film Festival.

As a fan of your work, I was excited when the film began with an extended shot of someone driving—I thought, “Yes, we’re back.” So it was surprising when the car stopped, and you followed the driver as he exited; I feel that maneuver is not typical in your films. Was there a desire to subvert the conventional car-driving scene?

There were several factors I considered for that scene. I couldn’t shoot it outdoors because if I did, I would need a larger car, position this car on it, and use the camera from specific angles. The police would have discovered that I was filming. Therefore, I was compelled to shoot that scene in a studio, creating the background for it. This was my first experience doing something like that.

I wanted to have that character step out of his car because I wanted the audience to hear the sound of his footsteps. More than wanting to break tradition in Iranian cinema, my focus was on the content. We begin with a shot of three people, then follow him out, and you see it revert back to just two people—the driver and his daughter. This wouldn’t be possible without combining two or three smaller shots to create this continuous moment.

I was curious how you found such an ideal stretch of road for that scene. You completely deceived me.

[Laughs] I’m glad it appeared seamless.

Your cinematographer, Amin Jafari, has mentioned the extensive use of natural light and available sources—streetlights, car lights. The film looks stunning and doesn’t show any limitations in resources. Do you think this choice ultimately benefits the film? Or were there specific instances during production where you wished for more extensive tools?

Even if we had the freedom to take two trucks of lighting with us, we would still approach it the same way. I believe we should depict precisely what we

Other articles

Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus opens pre-orders for physical editions on Nintendo Switch.

Fans of BJ Blazkowicz will be excited to know that Limited Run Games will start pre-orders for three physical editions of Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus for the Nintendo Switch on October 17th.

Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus opens pre-orders for physical editions on Nintendo Switch.

Fans of BJ Blazkowicz will be excited to know that Limited Run Games will start pre-orders for three physical editions of Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus for the Nintendo Switch on October 17th.

Cosmic horror film Beyond the Drumlins reveals its trailer and poster.

Black Mandala Films has unveiled a trailer and posters for Beyond the Drumlins, the forthcoming cosmic horror film by writer-director Dan Bowhers. The story follows a professor's archaeological expedition…

Cosmic horror film Beyond the Drumlins reveals its trailer and poster.

Black Mandala Films has unveiled a trailer and posters for Beyond the Drumlins, the forthcoming cosmic horror film by writer-director Dan Bowhers. The story follows a professor's archaeological expedition…

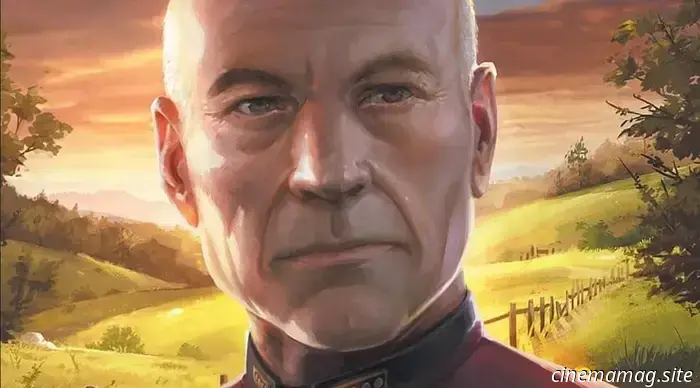

Review of the Comic Book – Star Trek: Picard Omnibus

Villordsutch reviews the Star Trek: Picard Omnibus… Unfortunately, we’re still without Star Trek: Legacy. The fantastic third season of Picard concluded two years ago, and yet we find ourselves still waiting. In the me…

Review of the Comic Book – Star Trek: Picard Omnibus

Villordsutch reviews the Star Trek: Picard Omnibus… Unfortunately, we’re still without Star Trek: Legacy. The fantastic third season of Picard concluded two years ago, and yet we find ourselves still waiting. In the me…

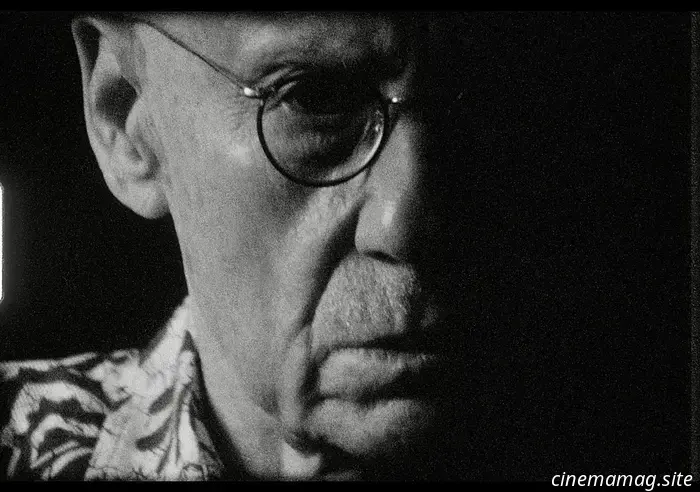

Exclusive Trailer for Ellroy vs. L.A. Delves into the Psyche of a Noir Legend

Few writers capture the essence of the City of Angels like James Ellroy, renowned for works such as The Black Dahlia and L.A. Confidential. His life and career in relation to the city are explored in the latest documentary directed by Francesco Zippel (Friedkin Uncut), titled Ellroy vs. L.A. This documentary includes an exclusive interview and archival footage that delve into Ellroy's connections with the city. Before its premiere,

Exclusive Trailer for Ellroy vs. L.A. Delves into the Psyche of a Noir Legend

Few writers capture the essence of the City of Angels like James Ellroy, renowned for works such as The Black Dahlia and L.A. Confidential. His life and career in relation to the city are explored in the latest documentary directed by Francesco Zippel (Friedkin Uncut), titled Ellroy vs. L.A. This documentary includes an exclusive interview and archival footage that delve into Ellroy's connections with the city. Before its premiere,

Bleeker Street has released the trailer for Rebuilding, featuring Josh O’Connor.

In anticipation of its release this November, Bleecker Street has unveiled a poster and trailer for the forthcoming drama Rebuilding. Penned and directed by Max Walker-Silverman, the film centers on Dusty (Josh O...

Bleeker Street has released the trailer for Rebuilding, featuring Josh O’Connor.

In anticipation of its release this November, Bleecker Street has unveiled a poster and trailer for the forthcoming drama Rebuilding. Penned and directed by Max Walker-Silverman, the film centers on Dusty (Josh O...

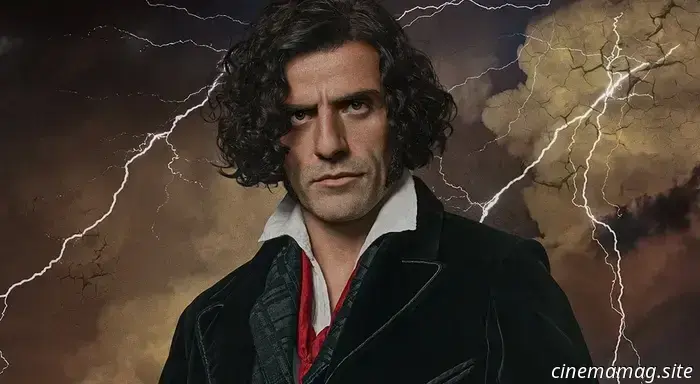

Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein releases a series of character posters.

Netflix has released five new character posters for Guillermo del Toro's celebrated adaptation of the literary classic Frankenstein, showcasing Oscar Isaac as Victor Frankenstein and Jacob Elordi as Th...

Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein releases a series of character posters.

Netflix has released five new character posters for Guillermo del Toro's celebrated adaptation of the literary classic Frankenstein, showcasing Oscar Isaac as Victor Frankenstein and Jacob Elordi as Th...

"We Must Describe Precisely What We Observe": Jafar Panahi Discusses It Was Just an Accident

Jafar Panahi comes to the United States embodying both a historical context and a fresh perspective. His reputation alone would suffice, as he stands as one of Iran's foremost filmmakers, a contemporary and collaborator of figures such as Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Mohammad Rasoulof, and especially Abbas Kiarostami––beyond merely directing his own scripts, he is