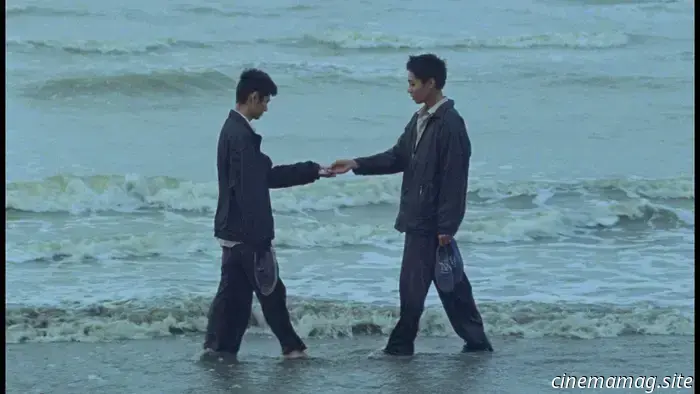

Việt and Nam Review: A Heartfelt, Evocative Slow Cinema Love Story

Note: This review was initially published as part of our coverage of the 2024 New York Film Festival. Việt and Nam is set to be released in theaters on March 28 by Strand Releasing.

“Keep the light on. It’s easier for me to dream.”

The opening scene of Việt and Nam, the second film from writer-director Trương Minh Quý, is a remarkable display of cinematic restraint. Almost indistinguishable white specks of dust gradually appear, originating from the top of a completely black screen and floating downwards, where the faintest outline of something can be perceived within the engulfing darkness. The sound design is both vast and intimate, filled with breaths and the sound of flowing water. A boy slowly enters the frame, moving from one corner to the other, carrying another boy on his back. A dream is softly shared through voiceover. Then, just as the frame has barely begun to manifest, it disappears.

This is Slow Cinema at its most intentional, evoking emotions one might not have been aware of, leading to insights one may never have reached, all while creating a contemplative space for the viewer to simply exist. It does not sacrifice entertainment in this pursuit. The time taken in each scene is justified, allowing the narrative to amuse, engage, excite, unsettle, or soothe at any moment. The stillness and repetition are so tastefully stretched that they could belong to a John Cale album.

The narrative of Việt and Nam revolves around two slender, gentle boys who discovered love thousands of feet underground in the coal mine where they work. It is deeply entwined with the tragic legacy of the Vietnam War, which left many Vietnamese children without fathers and often entirely alone. This history looms over the characters—especially Nam, whose father was never found dead or alive after two decades of conflict. Like countless others, Nam’s father is an unmarked grave somewhere in the jungle, a spiritual loss that violates his soul according to certain Vietnamese beliefs, with his spirit aimlessly wandering until his family finds him: a seemingly insurmountable challenge.

The film also addresses human trafficking, a perilous and regrettably hopeful path for impoverished individuals in Vietnam, including Nam and his mother, Hoa (played by Thi Nga Nguyen in a remarkable performance, which serves as an enlightening portrayal for mothers seeking connection with their queer sons). Much to Viet’s dismay, Nam aspires to emigrate for a better life that he envisions for them, resorting to illegal means to achieve it.

Nam, of course, does not wish to go alone, but Viet is hesitant about the idea and distrusts the process. He knows it would involve many terrifying moments, such as being sealed in a plastic bag and pulled underwater by a swimmer above or being shut inside a refrigerated shipping container that is expected to cross the ocean on a cargo vessel, somehow addressing their needs for air, water, food, and a reliable guide. Unsurprisingly, it is easy to empathize with Viet when recognizing the inherent dangers, but this perspective comes from the comfort of a theater seat, and they are not in such a position. Moreover, Nam remains resolute, and they cannot fathom being apart.

Before departing, Nam wishes to locate his father. Alongside his mother, Viet, and one of his father’s former comrades, they travel to an area where the old soldier believes Nam’s father may have perished, only to encounter others searching for the same, some accompanied by psychics for guidance. Families mourn and drift behind the ghostly clairvoyant, accepting whatever the psychic declares as truth—even claiming that the soil is their relatives' bones.

Elements like these, along with the aspiration for a better life and the overarching themes regarding the nation’s identity, have led to the film being rejected by its home country before its premiere at Cannes. The Vietnam Cinema Department issued an official letter denouncing its “gloomy, deadlocked, and negative” portrayal of the country and its inhabitants. In other words, it failed state-required censorship. Minh Quý has pushed back against this, hoping viewers perceive the film as “a tender and emotional expression of what is transpiring in the country from a Vietnamese filmmaker's perspective.”

The film grading, scanned with Cintel technology, is stunning, highlighting the texture of Son Doan’s 16mm cinematography. The depth and darkness of the color palette create distinct contrasts between the oppressive darkness of the mine and the vibrant greens of the Vietnamese countryside in daylight. Vincent Villa’s immersive and precise sound design stands out as one of the most impactful this year.

There is a deeply felt, physical romance between Viet and Nam that emerges in the mines, their faces stained with soot, their heads camouflaged as they emerge from their dark work uniforms, complemented by their black hair and boots. The starlight reflecting off the quartz embedded in the black anthracite walls they lean against creates an intimate yet expansive night

Other articles

The Open Alpha playtest for Shadow of the Road has launched on Steam.

Owlcat Games and developer Another Angle Games have revealed that the first Open Alpha playtest for their upcoming turn-based RPG, Shadow of the Road, is now accessible on Steam for PC. Players can explore a mythological feudal Japan infused with steampunk technology. Check out the new trailer below for a preview […]

The Open Alpha playtest for Shadow of the Road has launched on Steam.

Owlcat Games and developer Another Angle Games have revealed that the first Open Alpha playtest for their upcoming turn-based RPG, Shadow of the Road, is now accessible on Steam for PC. Players can explore a mythological feudal Japan infused with steampunk technology. Check out the new trailer below for a preview […]

15 Unanticipated Movie Deaths

These movie deaths caught everyone off guard. Spoilers are coming, of course.

15 Unanticipated Movie Deaths

These movie deaths caught everyone off guard. Spoilers are coming, of course.

Marvel reveals the cast of Avengers: Doomsday through a live video as filming commences.

Marvel Studios is experimenting with live stream-style announcements for its new projects, but is this the most effective way to introduce these stories? We'll find out, as the audience is currently discovering the cast for the upcoming superhero film Avengers: Doomsday in a newly released video announcement. During a live-stream event across […]

Marvel reveals the cast of Avengers: Doomsday through a live video as filming commences.

Marvel Studios is experimenting with live stream-style announcements for its new projects, but is this the most effective way to introduce these stories? We'll find out, as the audience is currently discovering the cast for the upcoming superhero film Avengers: Doomsday in a newly released video announcement. During a live-stream event across […]

10 Amazing Overlooked Treasures from the 1980s

We explore ten fantastic overlooked treasures from the 1980s… How many of these have you watched? The 1980s was a diverse mix of films. Blockbusters and franchises started to gain significant popularity. The rise of home video provided an opportunity for movies to thrive outside of theaters as well. Film enthusiasts have consistently gathered in […]

10 Amazing Overlooked Treasures from the 1980s

We explore ten fantastic overlooked treasures from the 1980s… How many of these have you watched? The 1980s was a diverse mix of films. Blockbusters and franchises started to gain significant popularity. The rise of home video provided an opportunity for movies to thrive outside of theaters as well. Film enthusiasts have consistently gathered in […]

Trailer for Salvable featuring Toby Kebbell, Shia LaBeouf, and James Cosmo.

Lionsgate has unveiled a poster and trailer for the upcoming crime drama Salvable, directed by Bjorn Franklin and Johnny Marchetta. Featuring Toby Kebbell, Shia LaBeouf, and James Cosmo, the film centers on the life of an aging boxer who faces challenges both in the ring and in his personal life as he attempts to regain control when he relapses into...

Trailer for Salvable featuring Toby Kebbell, Shia LaBeouf, and James Cosmo.

Lionsgate has unveiled a poster and trailer for the upcoming crime drama Salvable, directed by Bjorn Franklin and Johnny Marchetta. Featuring Toby Kebbell, Shia LaBeouf, and James Cosmo, the film centers on the life of an aging boxer who faces challenges both in the ring and in his personal life as he attempts to regain control when he relapses into...

Tombstone is arriving in 4K Ultra HD, and it's bringing hell along with it.

Elevation has revealed that George P. Cosmatos' iconic 1993 western, Tombstone, will be released on 4K Ultra HD, accompanied by a limited edition SteelBook in April. Take a look at the cover art and further details here… Justice approaches as the legendary epic action-adventure, Tombstone, returns on 4K Ultra HD.

Tombstone is arriving in 4K Ultra HD, and it's bringing hell along with it.

Elevation has revealed that George P. Cosmatos' iconic 1993 western, Tombstone, will be released on 4K Ultra HD, accompanied by a limited edition SteelBook in April. Take a look at the cover art and further details here… Justice approaches as the legendary epic action-adventure, Tombstone, returns on 4K Ultra HD.

Việt and Nam Review: A Heartfelt, Evocative Slow Cinema Love Story

Note: This review was initially published as part of our coverage for the 2024 New York Film Festival. Việt and Nam will be released in theaters on March 28 by Strand Releasing. “Keep the light on. It helps me dream more easily.” The film begins with an impressive shot, marking the second feature from writer-director Trương Minh Quý.