Cannes Review: Lav Diaz's Magellan is a Captivating, Clear Examination of the Atrocities of Colonization.

Ferdinand Magellan has not historically been viewed as a significant figure, and Lav Diaz’s unexpectedly conventional––yet still mesmerizing––biopic employs genre conventions to further challenge his legacy. Initially conceived as a project centered on Magellan’s wife Beatriz, this film now serves as an unusual companion piece: unmistakably the work of Diaz, yet inherently incomplete, often making large temporal jumps that clash with the more deliberately paced narratives we typically associate with him. During a pre-Cannes screening, the film's PR representative noted how each work-in-progress cut varied significantly in length, and the final, festival-bound version still bears the influence of a reported nine-hour black-and-white film shot from Beatriz’s viewpoint. This might explain why, despite its considerable runtime––as the joke goes, 156 minutes is brief for Diaz––it feels as though we are only beginning to delve into a richer portrayal of Magellan's colonial endeavors and their repercussions in Portugal and the Philippines.

However, this does not imply that Diaz's clear depiction of the atrocities of colonialism is diminished by the frequent time jumps; even as we move years between significant events in the explorer's life, the impact on victims remains starkly evident. The acts of brutality primarily occur offscreen, starting with a striking introduction where residents of a Philippine island express their gratitude for the approaching “white man.” Following this, a title card appears, promptly followed by the sight of countless faceless bodies washed ashore after a battle that is not elaborated upon in detail. This jarring opening lingers as Magellan’s personal objective transforms into converting these isolated communities to Christianity, a pursuit that he desperately tries to reconcile with the core principles of the religion, showing a troubling lack of self-awareness.

Though nearly two decades separate these two significant moments in his life, Diaz unifies them with a rightly cynical perspective on the connection between religion and colonization, where the human cost of spreading this message is never underestimated. Again, there are no battle scenes depicted; only the anonymous bodies strewn across remote village floors, lifelessly peering into the frame—a constant reminder of the brutality that these indifferent figures have long endured. It’s important to highlight that Gael García Bernal’s performance gains strength the more detached it appears from the historical events surrounding Magellan, embodying the violent colonial mentality suited for a film that reflects solely on death rather than the circumstances that lead to it.

Of course, my critiques of conventionality come with the caveat of a slow-cinema tendency. Diaz does not rush through eras; instead, every sequence feels like a meticulously detailed illustration, leading to what unmistakably feels like an overview of a pivotal historical figure and the colonial horrors of the time—unflinching in its documentation but still far from a comprehensive narrative. Disappointingly, there are hints of deeper thematic explorations that could subvert the “great man” biopic genre, but these remain largely unsaid until Diaz sharpens his commentary on the events leading to Magellan’s demise, playfully manipulating historical fact––though not outright revising it––in a way that made me yearn for a perspective outside the explorer's limited viewpoint.

This film serves as a significant commentary on the way cinema reinterprets historical narratives––often establishing a definitive interpretation of contested facts, even when narrative liberties are taken––but feels confined within a lesser work. The circumstances surrounding Magellan’s death at the Battle of Mactan have only one documented witness, and by ultimately questioning the reliability of this sole narrator, Diaz creates an illusion of a more profound genre reconstruction than what is portrayed onscreen. Within the work itself, Diaz seems to challenge convention primarily through omission; the one major battle scene is a deliberately anti-climactic, static shot of three ships awkwardly firing cannons at one another, resembling an anti-Master and Commander.

As Magellan's Spanish expedition progresses, his wife Beatriz (Ângela Ramos) emerges as a somewhat ghostly presence, a constant reminder of the more fully developed perspective that is likely still being shaped in post-production. It was through researching her that Diaz’s motivation to explore this era was ignited, but Magellan often feels like a necessary, surprisingly accessible piece that would secure funding for his more ambitious project. There is much to appreciate here, yet I never felt I was witnessing a fully realized vision.

Magellan had its premiere at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

Other articles

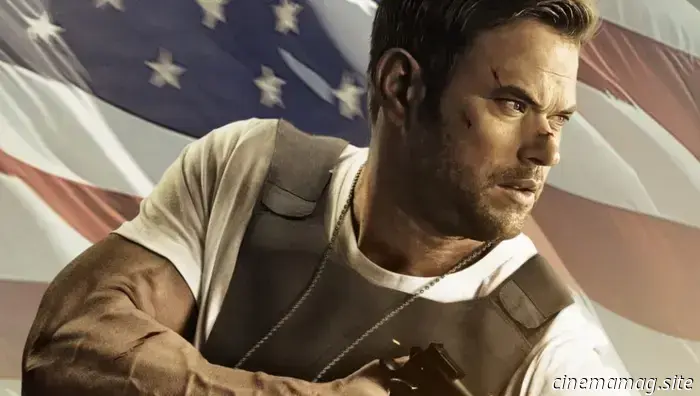

Kellan Lutz discusses the Twilight reunion with Cam Gigandet in Desert Dawn - Exclusive Interview

Tai Freligh speaks with Kellan Lutz regarding Desert Dawn… In Desert Dawn, Kellan Lutz (Twilight Saga, Immortals, Extraction) portrays a newly appointed sheriff in a small town, alongside his hesitant deputy, played by Cam Gigandet (Priest, Twilight Saga, Love Hurts). Together, they become embroiled in a complex web of deceit and corruption following the murder of a mysterious individual.

Kellan Lutz discusses the Twilight reunion with Cam Gigandet in Desert Dawn - Exclusive Interview

Tai Freligh speaks with Kellan Lutz regarding Desert Dawn… In Desert Dawn, Kellan Lutz (Twilight Saga, Immortals, Extraction) portrays a newly appointed sheriff in a small town, alongside his hesitant deputy, played by Cam Gigandet (Priest, Twilight Saga, Love Hurts). Together, they become embroiled in a complex web of deceit and corruption following the murder of a mysterious individual.

Cannes Review: Drunken Noodles is an Alluring and Uniquely Soothing Drama

The laws of time and space are playfully challenged in Drunken Noodles, Lucio Castro’s highly anticipated third feature and undoubtedly the standout title in this year’s ACID lineup. Many who are familiar with the New York-based, Argentinian-born director first came across his work through End of the Century, a film that shares a similar approach to time: set in Barcelona,

Cannes Review: Drunken Noodles is an Alluring and Uniquely Soothing Drama

The laws of time and space are playfully challenged in Drunken Noodles, Lucio Castro’s highly anticipated third feature and undoubtedly the standout title in this year’s ACID lineup. Many who are familiar with the New York-based, Argentinian-born director first came across his work through End of the Century, a film that shares a similar approach to time: set in Barcelona,

Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 - Comic Book Teaser

DC Comics will be launching Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 this Wednesday, and you can check out a preview of the issue below... “We Are Yesterday” Part Four (of six) The Batman and Superman from the past…in the present?! As Gorilla Grodd's brutal time attack on the Justice League persists, the Dark Knight and Man of […]

Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 - Comic Book Teaser

DC Comics will be launching Batman/Superman: World's Finest #39 this Wednesday, and you can check out a preview of the issue below... “We Are Yesterday” Part Four (of six) The Batman and Superman from the past…in the present?! As Gorilla Grodd's brutal time attack on the Justice League persists, the Dark Knight and Man of […]

-4K-Ultra-HD-Review.jpg) Starman (1984) - Review in 4K Ultra HD

Starman, 1984. Directed by John Carpenter. Featuring Jeff Bridges, Karen Allen, Charles Martin Smith, and Richard Jaeckel. SYNOPSIS: Previously available exclusively in the Columbia Classics: Volume 4 collection, the 4K Ultra HD edition of John Carpenter’s Starman is now released as an individual Steelbook edition. The set does not include the two discs that contain the single-season TV series, […]

Starman (1984) - Review in 4K Ultra HD

Starman, 1984. Directed by John Carpenter. Featuring Jeff Bridges, Karen Allen, Charles Martin Smith, and Richard Jaeckel. SYNOPSIS: Previously available exclusively in the Columbia Classics: Volume 4 collection, the 4K Ultra HD edition of John Carpenter’s Starman is now released as an individual Steelbook edition. The set does not include the two discs that contain the single-season TV series, […]

Cannes Review: Lynne Ramsay’s Die My Love Resonates Emotionally Despite Jennifer Lawrence’s Powerful Performance

Just before the climax of Lynne Ramsay's You Were Never Really Here, two assassins—one elegantly attired but fading, the other disheveled yet very much alive—found themselves on the kitchen floor, their hands softly brushing against each other as Charlene's "Never Been to Me" played softly from a nearby radio, the words barely escaping the lips of the injured man. That striking contrast

Cannes Review: Lynne Ramsay’s Die My Love Resonates Emotionally Despite Jennifer Lawrence’s Powerful Performance

Just before the climax of Lynne Ramsay's You Were Never Really Here, two assassins—one elegantly attired but fading, the other disheveled yet very much alive—found themselves on the kitchen floor, their hands softly brushing against each other as Charlene's "Never Been to Me" played softly from a nearby radio, the words barely escaping the lips of the injured man. That striking contrast

Cannes Review: Lav Diaz's Magellan is a Captivating, Clear Examination of the Atrocities of Colonization.

Ferdinand Magellan has not typically been seen as a significant figure in history, and Lav Diaz’s unexpectedly traditional––though still captivatingly slow––biopic employs a genre framework to further disavow his legacy. Originating from a long-planned project centered on Magellan’s wife Beatriz, the film now serves as an unconventional companion of sorts: it is a piece that you could never confuse for