Cannes Review: Bi Gan’s Resurrection is a Remarkable Display of Boldness and Outstanding Skill

Few filmmakers, with only two features to their name, have captured the fervent, cinephile admiration that Bi Gan has garnered. His unique blend of surreal narrative, hyper-real aesthetics, and a mind-bending manipulation of time transforms rural China into a mesmerizing spectacle. After a seven-year hiatus following Long Day’s Journey Into Night, the anticipation for his third film has finally come to an end. Debuting in competition at Cannes, Resurrection marks a new direction for the writer-director, while also fulfilling the expectations of his audience. Narratively and stylistically versatile, it presents a sci-fi-infused, century-spanning cinematic tapestry that profoundly invites viewers to envision. Bi Hive, celebrate: this is Palme-worthy material.

A 20-minute prologue introduces the notion of “fantasmers,” a select group of individuals who persist in dreaming in a world that has abandoned this practice. These outliers are hunted by a group, including one played by Shu Qi. In this opening, devoid of dialogue and reminiscent of silent cinema, we follow the hunter as she scours for a known fantasmer (Jackson Yee), whom she eventually apprehends and, in a gesture of compassion, allows to experience a few more dreams before he passes away.

The remainder of Resurrection is made up of four dreams wherein the fantasmer is reincarnated as various characters from different eras. The only unifying theme among these 20-to-30-minute segments is their otherworldly logic, seemingly providing the protagonist with a chance to rectify wrongs or mitigate regrets. In the first segment set during WWII, he is a young man being interrogated under suspicion of murder. The initially straightforward premise quickly disintegrates into fragmented memories involving mysterious suitcases and mirror shops. The second vignette, occurring a few decades later, features the protagonist on a mission at a snow-covered Buddhist temple. After the rest of his group mysteriously vanishes, he begins a conversation with someone who may or may not be the tooth he just lost. The third narrative sees the dreamer taking on the role of a street-wise con artist who enlists a young girl as his accomplice to swindle a mobster. The fourth and most substantial dream follows the protagonist as he chases after a beautiful singer on the cusp of the new millennium. Will they witness the sunrise together if she is revealed to be a vampire?

Through this collage-style format, Bi Gan evidently departs from the narrative frameworks established in Kaili Blues and Long Day’s Journey Into Night. While one might argue that this shift diffuses the impact of a cohesive storyline, Bi's aspirations extend beyond constructing a singular dream environment; he delves into the philosophical, existential themes of dreams and presents the past century of cinema as a chronicle of those themes. Across the film’s five segments (including the prologue and epilogue), Bi illustrates five distinct cinematic styles, affirming that the silver screen has always served as a means of escaping reality; and that, as both creators and audiences of cinema, we contribute to the preservation of dreaming in an increasingly unimaginative world.

This is a highly ambitious endeavor where certain segments resonate more effectively than others. The opening and closing sequences, supported by title cards and orchestral music, may require some adjustment but ultimately charm with their frantically retro style. The segment set in the 1940s, characterized by its stark visuals and enigmatic dialogue, is perhaps the least accessible but evokes the tradition of spy thrillers interwoven with classic paranoia. The remaining parts of Resurrection recall Bi's distinctive, delightfully perplexing storytelling.

The New Year’s Eve scene, in particular, is a remarkable achievement. Filmed in one continuous 30-minute shot, it presents fewer logistical challenges than a similar scene from Long Day’s Journey Into Night; however, it’s evident that Bi has grown more confident in his vision and execution of the shot. There’s a casual fluidity to the unfolding action as two characters navigate through the neighborhood, instantly creating a surreal, trance-like ambiance. At one moment, the camera unexpectedly shifts to a first-person perspective; later, it seamlessly returns to a neutral observer. These artistic choices—such as the dramatic color shift that occurs upon a character’s sudden entrance into a room—are breathtaking. Kudos also go to DP Dong Jinsong and production designer Liu Qiang for their exceptional craftsmanship that completed this illusion.

Throughout Cannes’ nearly 80-year history, Chen Kaige’s Farewell, My Concubine remains the only Chinese-language film to win the Palme d’Or (shared with Jane Campion’s The Piano in 1993). Due to its innovative form, breadth of ideas, and audacity to redefine cinematic language, Resurrection deserves a place on that very short list.

Resurrection premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

Other articles

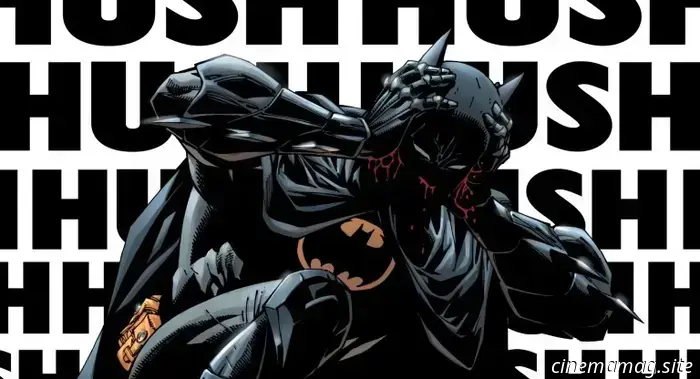

Batman #160 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics is launching Batman #160 this Wednesday, and you can check out an exclusive preview of the issue below. The character's name is Silence, and his partnership with Hush poses a significant threat to Batman! Batman #160 will be available for purchase on May 28th, with a price of $4.99.

Batman #160 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

DC Comics is launching Batman #160 this Wednesday, and you can check out an exclusive preview of the issue below. The character's name is Silence, and his partnership with Hush poses a significant threat to Batman! Batman #160 will be available for purchase on May 28th, with a price of $4.99.

Ranking All 11 Mel Brooks Films From Good to Classic

Here are the rankings of 11 Mel Brooks films.

Ranking All 11 Mel Brooks Films From Good to Classic

Here are the rankings of 11 Mel Brooks films.

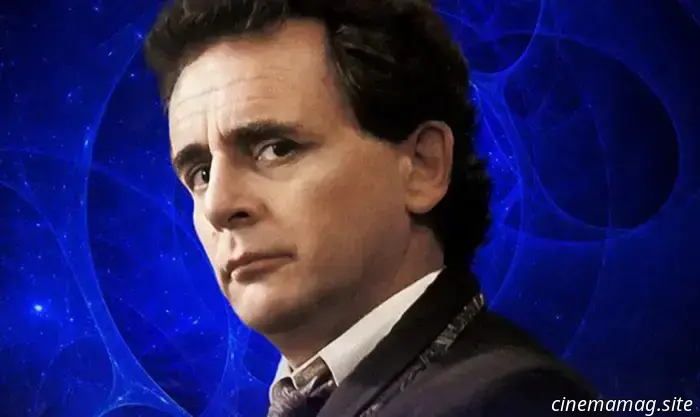

A new previously unreleased Doctor Who story featuring the Seventh Doctor will be released by Big Finish this September.

Big Finish has revealed that the new Doctor Who – The Lost Stories: Alixion audio drama will be released this September. This recent audio box set in The Lost Stories series presents a brand-new adventure featuring the Seventh Doctor, once more portrayed by the fantastic Sylvester McCoy. The Lost Stories series consists of audio dramas inspired by unproduced [...]

A new previously unreleased Doctor Who story featuring the Seventh Doctor will be released by Big Finish this September.

Big Finish has revealed that the new Doctor Who – The Lost Stories: Alixion audio drama will be released this September. This recent audio box set in The Lost Stories series presents a brand-new adventure featuring the Seventh Doctor, once more portrayed by the fantastic Sylvester McCoy. The Lost Stories series consists of audio dramas inspired by unproduced [...]

Jeffrey Brown adds his unique touch to Marvel through new variant covers.

Marvel Comics has revealed that Eisner Award-winning illustrator Jeffrey Brown (known for Star Wars: Darth Vader and Son, Thor and Loki: Midgard Family Mayhem) will once again provide his distinctive interpretation of the Marvel Universe this August, creating three brand-new variant covers for the Incredible Hulk, Thor, and X-Men issues. “As a child, it was always a […]

Jeffrey Brown adds his unique touch to Marvel through new variant covers.

Marvel Comics has revealed that Eisner Award-winning illustrator Jeffrey Brown (known for Star Wars: Darth Vader and Son, Thor and Loki: Midgard Family Mayhem) will once again provide his distinctive interpretation of the Marvel Universe this August, creating three brand-new variant covers for the Incredible Hulk, Thor, and X-Men issues. “As a child, it was always a […]

Predator vs. Spider-Man #2 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Marvel's comic book crossover Predator vs. Spider-Man continues this Wednesday with the launch of its second issue. You can check out the official preview below... SKINNER’S SLAUGHTER CARRIES ON! The highest temperatures of the season have caused a blackout in New York, and a Predator hunts through the shadowy streets. This Predator is unlike any other…

Predator vs. Spider-Man #2 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Marvel's comic book crossover Predator vs. Spider-Man continues this Wednesday with the launch of its second issue. You can check out the official preview below... SKINNER’S SLAUGHTER CARRIES ON! The highest temperatures of the season have caused a blackout in New York, and a Predator hunts through the shadowy streets. This Predator is unlike any other…

Cannes Review: Bi Gan’s Resurrection is a Remarkable Display of Boldness and Outstanding Skill

Few directors who have only two films to their name can gather the fervent, film-loving audience that Bi Gan has. His unique mix of surreal narrative, hyper-real visual style, and a mesmerizing manipulation of time turns the countryside of China into a realm of entrancing beauty. Seven years following Long Day’s Journey Into Night, anticipation for his third film is