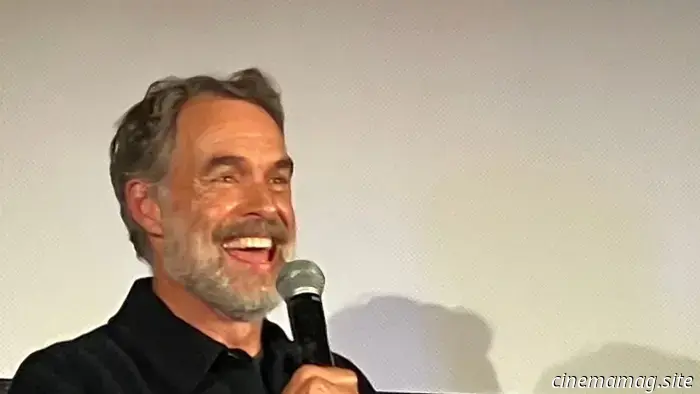

Kites director Walter Thompson-Hernandez discusses the violence and the poetic essence found in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

In the favelas of prominent Brazilian cities like Rio de Janeiro, it's quite common to spot vibrant kites decorating the skyline. These informal settlements, or slums, have become closely associated with kites and kite festivals, where locals use bamboo and paper to preserve this traditional pastime.

This striking image left a lasting impression on filmmaker Walter Thompson-Hernandez, who was moved by the contrast between this innocent activity and the police violence occurring in the same neighborhoods. It inspired him to create "Kites," an entry for the Tribeca Festival that made its world debut there.

“I sensed that there was a compelling story to tell, a film that captures the bittersweet beauty of life,” he shared with MovieMaker. “On one side, there’s the joy of flying kites, pure and sincere. On the other side, there’s death and police brutality. To me, 'Kites' represents a long visual poem that deviates from traditional narratives. It features vignettes about three or four different individuals living in this community.”

The film took five years to complete. Thompson-Hernandez raised $100,000 and persuaded a group of friends in Brazil to participate. Another friend composed the music, and he relied on a fluid outline to stay true to the characters in the most organic way possible. There was no script; instead, improvisation prevailed, resulting in themes of life, love, and duality.

We spoke with Thompson-Hernandez about his distinctive approach to this film, the experience of filming in Brazil, and the significance of accurately portraying these characters and real-life favelas on an international stage.

Walter Thompson-Hernandez on the Unique Filming Process of "Kites"

Amber Dowling: Did this lengthy process take longer than you expected due to your filming and editing methods?

Walter Thompson-Hernandez: It took exactly as long as it needed to. We made six trips to Brazil, each lasting five or six days. After our third trip, I thought we had completed it. However, during editing, I discovered more nuances and revelations. Eventually, I recognized the potential for a stunning element of protection by introducing guardian angels. The project continued to evolve in a way that felt both beautiful and thought-provoking.

Amber Dowling: The inclusion of angels and elements of magical realism connects your vignettes. Can you elaborate on how you wove them into the film?

Walter Thompson-Hernandez: They emerged from discussions with friends who had family members and acquaintances affected by police violence. These conversations led to profound late-night discussions about the nature of protection, safety, and divinity. I concluded that many believe in some form of guardianship. What if our protective angel indulged in vices like smoking cigarettes in heaven or having their hair styled by an angelic companion? It’s absurd yet beautiful and authentic, much like the film itself. It embraces imperfections and beauty, reflecting a sincere, extended poem.

Amber Dowling: Given that this film took five years to create, the actors don’t appear to have aged on screen. Did you employ any tricks?

Walter Thompson-Hernandez: No, it’s amusing because the actors look fantastic. However, the children’s voices did change over five years. Sometimes after returning to Brazil, I noticed someone’s voice had deepened or their personality had shifted. We never knew what kind of child we would encounter.

Amber Dowling: What does it signify for you to share this film outside Brazil?

Walter Thompson-Hernandez: I have tremendous affection for the contributions of my friends. They were all first-time actors, and their excitement about watching this film makes it feel special. This story is deeply rooted in a specific context, in Rio and its neighborhoods, yet it conveys a universally relatable message of hope, protection, and redemption.

It prompts a reflection on our actions: How are they perceived in the eyes of God and one another? What does it mean for us to strive for goodness while hoping for the best?

Amber Dowling: Your main character is a drug dealer who also funds a community kite festival. What messages did you intend to convey with this duality?

Walter Thompson-Hernandez: This film delves into existential themes. It unfolds amidst what I envision as an existential crisis, showcasing a character who, despite being a drug dealer, yearns to do good and possesses kindness. He has a mother and a family he believes he’s supporting rightfully. It raises profound questions about life, our roles, and the choices we make during our time on earth.

Amber Dowling: How did you want to portray the kites themselves in the film?

Walter Thompson-Hernandez: Each favela hosts an annual kite festival, which likely ranks as one of the most significant days of the year, second only to Carnival. I wanted to position this as a climax, underscoring the beautiful, multi-generational connection that these favelas create, in contrast

Other articles

Murray Bartlett discusses The White Lotus and the experience of losing his front teeth — PIFF 2025.

When Murray Bartlett relocated to the Provincetown, Massachusetts region a few years back, he was concerned that it might affect his acting opportunities. He had transitioned from his home state.

Murray Bartlett discusses The White Lotus and the experience of losing his front teeth — PIFF 2025.

When Murray Bartlett relocated to the Provincetown, Massachusetts region a few years back, he was concerned that it might affect his acting opportunities. He had transitioned from his home state.

The September lineup from The Criterion Collection includes High and Low, Wes Anderson films, and Spinal Tap in 4K.

It is probable that Criterion was working on their 4K upgrade of High and Low—a film they released so long ago that it had already undergone a "high-definition digital transfer"—well in advance of any timeline established for Spike Lee's Highest 2 Lowest. However, chance occurrences seldom hinge on such factors. In any event, Akira Kurosawa's epic story of a king's ransom remains significant.

The September lineup from The Criterion Collection includes High and Low, Wes Anderson films, and Spinal Tap in 4K.

It is probable that Criterion was working on their 4K upgrade of High and Low—a film they released so long ago that it had already undergone a "high-definition digital transfer"—well in advance of any timeline established for Spike Lee's Highest 2 Lowest. However, chance occurrences seldom hinge on such factors. In any event, Akira Kurosawa's epic story of a king's ransom remains significant.

12 Behind-the-Scenes Photos of Goldfinger Showcasing Bond at His Finest

12 Behind-the-Scenes Photos of Goldfinger Showcasing Bond at His Finest

Materialists Review: A Skeptical Romantic Comedy Lacking Essential Elements

Materialists is a film featuring a traditional screwball premise: a young, attractive matchmaker encounters the dashing, wealthy man of her fantasies on the same evening she comes across her handsome, financially struggling ex-boyfriend. However, Celine Song's second feature adopts a more understated, dramatic tone to examine contemporary dating. Echoing the themes of Jane Austen, Materialists delves into

Materialists Review: A Skeptical Romantic Comedy Lacking Essential Elements

Materialists is a film featuring a traditional screwball premise: a young, attractive matchmaker encounters the dashing, wealthy man of her fantasies on the same evening she comes across her handsome, financially struggling ex-boyfriend. However, Celine Song's second feature adopts a more understated, dramatic tone to examine contemporary dating. Echoing the themes of Jane Austen, Materialists delves into

“The Film Reflects Reality”: Celine Song Discusses Materialism, Divine Love, and Self-Worth

Love is treated as a commodity in the second feature from Celine Song, who wrote and directed Past Lives. Dakota Johnson portrays Lucy, a matchmaker for a high-end dating service. Financial issues led to her split with John (Chris Evans), an actor facing challenges in his career. Harry (Pedro Pascal), a financier, presents her with the prospect of a lifestyle filled with extraordinary wealth. Romantic triangles often tend to

“The Film Reflects Reality”: Celine Song Discusses Materialism, Divine Love, and Self-Worth

Love is treated as a commodity in the second feature from Celine Song, who wrote and directed Past Lives. Dakota Johnson portrays Lucy, a matchmaker for a high-end dating service. Financial issues led to her split with John (Chris Evans), an actor facing challenges in his career. Harry (Pedro Pascal), a financier, presents her with the prospect of a lifestyle filled with extraordinary wealth. Romantic triangles often tend to

Kites director Walter Thompson-Hernandez discusses the violence and the poetic essence found in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

Kites director Walter Thompson-Hernandez discusses his unique approach to filming his Tribeca movie in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro using inexperienced actors.