Fantasia Review: Julie Pacino’s I Live Here Now is a Psychodrama That Welcomes Disturbing Humor

Rose (Lucy Fry) has always understood that she cannot bear children. This harsh reality stems from a traumatic childhood surgery that became embedded in her psyche as a nightmare, forming a significant aspect of her identity. It serves as a vital piece of her perceived brokenness. Therefore, she is unable to comprehend the shock of being told by her doctor that she is pregnant. The irony lies not only in the timing of this revelation, which comes after she was advised to lose three pounds for a potential acting opportunity, but also in the unfortunate coincidence of achieving a major career milestone just as the chance to start a family unexpectedly arises. Rose feels the need to escape the turmoil and discover what she truly wants, who she is, and who she might still become.

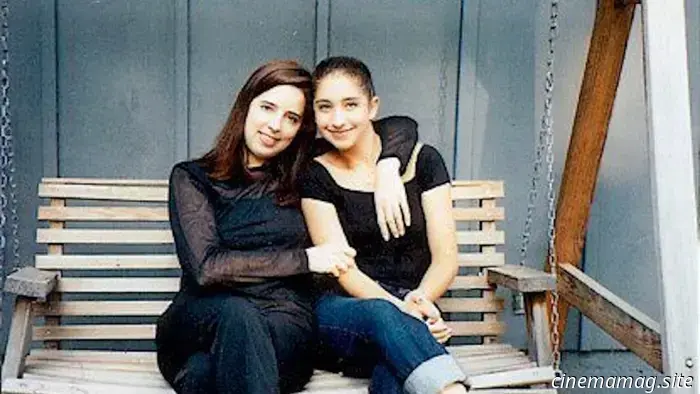

The debut feature from Julie Pacino (yes, she is Al’s daughter), I Live Here Now introduces a disquieting humor from the outset. There are notable, fateful events, such as talent agent Cindy Abrams (Cara Seymour) insisting on weight loss despite knowing Rose has no extra weight to shed (“maybe the character is starving”). A darkly absurd encounter with Travis’s mother, Martha (Sheryl Lee), reveals a controlling nature that essentially reduces her son’s semen to a family asset. The surreal, otherworldly ambiance of The Crown Inn, where Rose goes to ponder an abortion, is populated by the martini-holding manager (Lara Clear’s Ada) and the naively wholesome bellhop (Sarah Rich’s Sid). David Lynch’s Twin Peaks and Mulholland Dr. are clear influences.

This place isn’t quite what it appears to be. Rose’s sense of freedom is taken away (the valet will relocate her car from a tow-zone she was unaware of, which may not even exist). Her desires vanish as if to challenge her determination (first the script for her audition, then the abortion pill). She was informed a last-minute room became available, yet the heart-shaped key rack behind the counter is filled with unclaimed keys—not to mention Ada immediately "upgrading" her to a suite while she decides which key to use. Is it merely because “The Lovin’ Oven” appealed to her? Or does she somehow know about her pregnancy? And when Rose asks for a crib to be removed, Sid doesn’t apologize for its presence; instead, she expresses confusion, thinking Rose had brought it with her.

This makes little sense, unless The Crown Inn serves as more of a manifestation of Rose’s psyche than a physical structure. This could clarify why fellow resident Lillian (Madeline Brewer) ambiguously dismisses the idea that they are in a hotel, and why Sid’s pink Bible (detailing the establishment’s history) reads like a narrative of events we’ve already witnessed. The question becomes whether these women are ultimately figures from Rose’s past, fractured identities (with Sid representing childhood innocence overlooked and Lillian embodying the cavalier risk-taker often subdued), or perhaps both. Additionally, whether the rooms (sauna, dining area, fiery vents, and locked neighbors) contain memories or fears is another matter.

As reality blurs into hallucination, Rose’s body acts as a fail-safe mechanism to control the insanity when it spirals out of hand. Murder? Hidden sanatoriums? Better to have her awaken in bed as if it were all a terrible dream than to face meaning before she is prepared. Rose must contend not only with the baby, the audition, Lillian’s distractions, Ana’s indifference, and Sid’s sadness but also with the ominous presence of Martha, who wants her “property” back by any means necessary (the gradual bruising on Travis’s face as the story progresses is a nice touch). Themes of misogyny, guilt, fear, imposter syndrome, insecurity, and rage emerge. Rose has created a battleground of emotional and psychological triggers that keeps her confined unless she chooses to fight her way out.

It’s a captivating exploration of the challenges of womanhood. Societal expectations and norms surface so frequently that Rose struggles to distinguish where she ends and indoctrination begins. Fry gives a commendable performance in the lead role—assertive yet unsure. She serves as the straight character in contrast to Lee’s overtly malevolent portrayal, Brewer’s embrace of chaos, and Rich’s representation of lost innocence that may be rediscovered. At times, Pacino’s concepts and intentions overshadow the execution, but I appreciate the ambitious risks taken, which create a formidable character like Martha and a memorable moment with Sid and the lentil soup. I Live Here Now never conceals its metaphors, yet it ensures that our interpretations stem from within rather than being dictated by the filmmaker. Your reactions may vary, but its impact is undeniable.

I Live Here Now premiered at the 2025 Fantasia International Film Festival.

Other articles

The initial teaser for Park Chan-wook's No Other Choice reveals a striking intensity.

One of the major premieres revealed for this year's Venice Film Festival is Park Chan-wook's No Other Choice (with Neon managing the U.S. release), for which a short, rapid teaser has been released that suggests ties to Donald E. Westlake's source material, The Ax. This adaptation of the 1997 novel—originally filmed by Costa-Gavras in 2005—falls within the black comedy genre.

The initial teaser for Park Chan-wook's No Other Choice reveals a striking intensity.

One of the major premieres revealed for this year's Venice Film Festival is Park Chan-wook's No Other Choice (with Neon managing the U.S. release), for which a short, rapid teaser has been released that suggests ties to Donald E. Westlake's source material, The Ax. This adaptation of the 1997 novel—originally filmed by Costa-Gavras in 2005—falls within the black comedy genre.

How the Death of My Sister on 9/11 Inspired Me to Create the Ethics Resource Library for the Documentary Producers Alliance

Sarah Rachael Wainio discusses how the murder of her sister on 9/11 inspired her to establish the Ethics Resource Library for the Documentary Producers Alliance.

How the Death of My Sister on 9/11 Inspired Me to Create the Ethics Resource Library for the Documentary Producers Alliance

Sarah Rachael Wainio discusses how the murder of her sister on 9/11 inspired her to establish the Ethics Resource Library for the Documentary Producers Alliance.

Toxic Review: Saulė Bliuvaitė’s Drama, Awarded at Locarno, Will Embed Itself Within You

Note: This review was first published as part of our 2024 Riga coverage. Toxic is now available for streaming on MUBI. It's unfortunate that Toxic didn't release in time for the recent discussions surrounding body horror. Saulė Bliuvaitė's debut feature, which won the Golden Leopard at this year's Locarno Film Festival, contributes significantly to the genre.

Toxic Review: Saulė Bliuvaitė’s Drama, Awarded at Locarno, Will Embed Itself Within You

Note: This review was first published as part of our 2024 Riga coverage. Toxic is now available for streaming on MUBI. It's unfortunate that Toxic didn't release in time for the recent discussions surrounding body horror. Saulė Bliuvaitė's debut feature, which won the Golden Leopard at this year's Locarno Film Festival, contributes significantly to the genre.

New downloadable content now available for Sword Art Online: Fractured Daydream.

The latest DLC, Symphony of a Dazzling Dawn, has been released for Sword Art Online Fractured Daydream, introducing players to a wealth of new content, which includes a fresh scenario, additional playable characters, along with their respective weapons and outfits. Check out the new trailers below to meet these two characters… The scenario that comes with the Symphony of a Dazzling Dawn DLC has players […]

New downloadable content now available for Sword Art Online: Fractured Daydream.

The latest DLC, Symphony of a Dazzling Dawn, has been released for Sword Art Online Fractured Daydream, introducing players to a wealth of new content, which includes a fresh scenario, additional playable characters, along with their respective weapons and outfits. Check out the new trailers below to meet these two characters… The scenario that comes with the Symphony of a Dazzling Dawn DLC has players […]

NYC Weekend Viewing: Breathless, Barbara Loden, Birth, and More

NYC Weekend Watch is our weekly summary of repertory options. Roxy Cinema, in conjunction with a new 4K release, will show Jim McBride's Breathless on 35mm this Friday; City Dudes is back on Saturday; and a print of Snake Eyes will be screened over the weekend. At Film at Lincoln Center, there is a retrospective on Gene Hackman, showcasing a variety of his films on 35mm, including works by Clint Eastwood, William Friedkin, and Francis Ford.

NYC Weekend Viewing: Breathless, Barbara Loden, Birth, and More

NYC Weekend Watch is our weekly summary of repertory options. Roxy Cinema, in conjunction with a new 4K release, will show Jim McBride's Breathless on 35mm this Friday; City Dudes is back on Saturday; and a print of Snake Eyes will be screened over the weekend. At Film at Lincoln Center, there is a retrospective on Gene Hackman, showcasing a variety of his films on 35mm, including works by Clint Eastwood, William Friedkin, and Francis Ford.

Now Available for Streaming: Materialists, Dangerous Animals, Little Buddha, Northern Lights, and More

Every week, we showcase the significant titles that have recently become available on streaming services in the United States. Take a look at this week's picks below and previous compilations here. The Assessment (Fleur Fortune) The "old world" is a desolate place. People continue to exist there, but not for long. In contrast, those in the "new world" live for centuries, thanks to

Now Available for Streaming: Materialists, Dangerous Animals, Little Buddha, Northern Lights, and More

Every week, we showcase the significant titles that have recently become available on streaming services in the United States. Take a look at this week's picks below and previous compilations here. The Assessment (Fleur Fortune) The "old world" is a desolate place. People continue to exist there, but not for long. In contrast, those in the "new world" live for centuries, thanks to

Fantasia Review: Julie Pacino’s I Live Here Now is a Psychodrama That Welcomes Disturbing Humor

Rose (Lucy Fry) has always been aware that she cannot have children. The heartbreaking outcome of a surgery she underwent in childhood left a traumatic imprint on her mind, manifesting as a recurring nightmare, and this realization has become a significant aspect of her identity. It is a vital component of the puzzle that defines her perceived brokenness. This is the reason she struggles to understand.