David Lynch: The Significant Mystery of American Cinema

Simon Thompson examines the career of the late, legendary David Lynch…

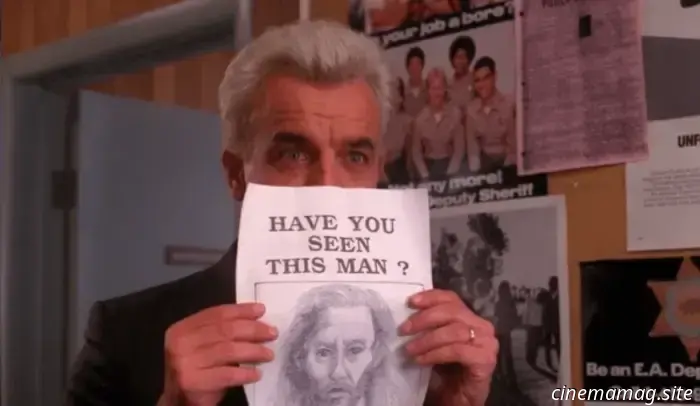

To begin this article in the simplest way possible, David Lynch, one of the most distinctive directors in American cinema, has passed away. Though I was aware that his health had sadly declined since 2020, it still feels nearly impossible to accept that an artist of Lynch’s extraordinary talent and originality is no longer here to provide his deeply sincere yet surreal, unyieldingly visceral portrayals of a nuanced and twisted Americana—so much so that fellow filmmaking icon and executive producer of two of his films, Mel Brooks, once described him as “Jimmy Stewart if he were from Mars.”

While he may not boast the extensive filmography (ten films and one groundbreaking television show) of other greats in American cinema, each of Lynch’s projects symbolizes a triumph of his artistic integrity over the formulaic and predictable fare that Hollywood produces in mass quantities.

David Lynch was born in January 1946 in Missoula, Montana to Donald and Sunny Lynch. Due to his father’s work as a research scientist for the USDA, the Lynch family relocated frequently during his childhood, living in various states including North Carolina and Washington.

Despite being an intelligent student and an Eagle Scout, Lynch found the educational setting creatively suffocating. He began to engage with cinema and painting, with his favorite film, The Wizard of Oz, serving as a continual reference point for his future work. The young Lynch was also captivated by the works of W.C. Fields, Federico Fellini, Alfred Hitchcock, Jacques Tati, and Billy Wilder.

Lynch’s passion for painting and drawing developed during his time in Virginia when he met a friend of his father’s who was a professional painter. After realizing that one could earn a living through art, Lynch immediately chose to pursue an artistic career. When he turned 18, he enrolled at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, D.C., but later transferred to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, where he shared a room with guitarist Peter Wolf.

However, Lynch found the School of the Museum of Fine Arts uninspiring, leading him to drop out after just one year. Freed from college obligations, he traveled to Austria with his friend Jack Fisk, aiming, as he mentioned in Lynch on Lynch, to study for three years under expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka without much research or a clear rationale. Upon arriving in Salzburg, they discovered that Kokoschka was not teaching there as they had thought and only ran a workshop. Disillusioned by Salzburg's "clean" ambiance, they returned home after fifteen days of traveling on the Orient Express. Following this unsuccessful trip, Lynch returned to America and enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

His time in Philadelphia marked a period of both social and creative growth for the young artist, who described the environment as being filled with “great and serious painters, inspiring one another in a beautiful time.” At the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, he met his first wife Peggy, with whom he had a daughter named Jennifer.

Living in the crime-ridden neighborhood of Fairmount in Philadelphia and supporting his family through various odd jobs, Lynch began making short films that would highlight the unique vision he eventually became known for. His newfound interest in filmmaking prompted a move to California, where he enrolled at the AFI conservatory and directed his debut feature Eraserhead.

Initially conceived as a 42-minute short, Eraserhead was primarily an exploration of Lynch’s experiences living in a less desirable area of Philadelphia alongside his wife and child. The film follows a mild-mannered young man named Henry (Jack Nance) living in a futuristic yet dilapidated urban landscape. After unexpectedly learning that his girlfriend is pregnant, she gives birth to—then abandons—a deformed baby (inspired by Lynch’s real-life fears regarding his daughter's health), compelling Henry to confront his anxieties about fatherhood and raising a child in such a dreadful setting.

Produced over three years from 1974 to 1977 during weekends and financed by Lynch through a combination of a $10,000 AFI grant, a loan from his father, and a paper route, Eraserhead became a deeply personal endeavor for Lynch. Following an amicable divorce from Peggy, he even lived on sets constructed for the film to immerse himself in the project as much as possible.

Shot in stark black and white and filled with disorienting, surreal, and grotesque imagery, Eraserhead possesses an elegiac yet oddly whimsical quality that distinguishes it from almost any other film. Lynch’s incorporation of German Expressionist angles and scale, along with a repetitive industrial score, establishes a suffocating atmosphere that echoes the beleaguered environments depicted in the film, creating a thematic dichotomy between the idyllic image of America and the harsher realities of life—an opposition shaped by Lynch’s idyllic Norman Rockwell-esque childhood and his

Other articles

Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe will feature in The Weight.

The Hollywood Reporter has announced a formidable collaboration between Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe. According to the publication, Hawke and Crowe will feature in The Weight, a forthcoming historical epic taking place in Oregon in 1933. Padraic McKinley is set to direct, utilizing an original screenplay written by Shelby Gaines, Matthew Chapman, and Matthew Booi, which is based on an original story [...]

Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe will feature in The Weight.

The Hollywood Reporter has announced a formidable collaboration between Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe. According to the publication, Hawke and Crowe will feature in The Weight, a forthcoming historical epic taking place in Oregon in 1933. Padraic McKinley is set to direct, utilizing an original screenplay written by Shelby Gaines, Matthew Chapman, and Matthew Booi, which is based on an original story [...]

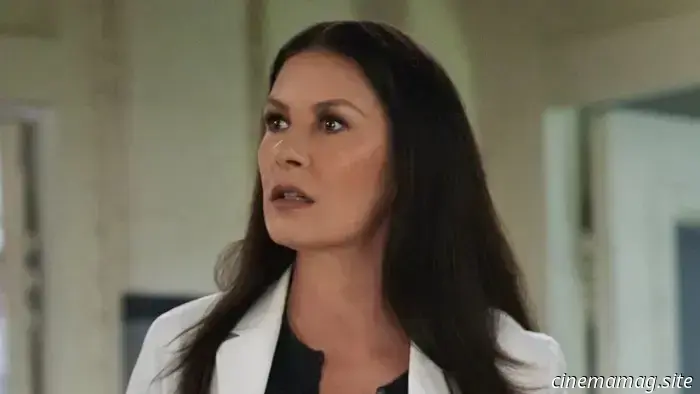

Catherine Zeta-Jones will lead the cast in the thriller series Kill Jackie.

The talented Oscar, BAFTA, and Tony Award-winning Catherine Zeta-Jones is set to take the lead in a new series based on Aidan Truhen's "gonzo thriller," The Price You Pay, which is currently working under the title Kill Jackie. According to Deadline, “the series is being produced for Prime Video, Fremantle, and Steel Springs Pictures. Amazon holds the rights in multiple [...]

Catherine Zeta-Jones will lead the cast in the thriller series Kill Jackie.

The talented Oscar, BAFTA, and Tony Award-winning Catherine Zeta-Jones is set to take the lead in a new series based on Aidan Truhen's "gonzo thriller," The Price You Pay, which is currently working under the title Kill Jackie. According to Deadline, “the series is being produced for Prime Video, Fremantle, and Steel Springs Pictures. Amazon holds the rights in multiple [...]

Director Adam Elliot's Memoir of a Snail: Crafting an Emotional Journey for His Audience and His Reason for Not Winning an Oscar

Twenty years ago, stop-motion animator Adam Elliot made his debut with the charming short film Harvie Krumpet. Centering on a man plagued by perpetual misfortune, it won him an Oscar and showcased Elliot's unique sense of humor, immense compassion, and distinctive animation style. A blend of the imperfect and the beautiful, entirely

Director Adam Elliot's Memoir of a Snail: Crafting an Emotional Journey for His Audience and His Reason for Not Winning an Oscar

Twenty years ago, stop-motion animator Adam Elliot made his debut with the charming short film Harvie Krumpet. Centering on a man plagued by perpetual misfortune, it won him an Oscar and showcased Elliot's unique sense of humor, immense compassion, and distinctive animation style. A blend of the imperfect and the beautiful, entirely

-Blu-ray-Review.jpg) Review of the Blu-ray Release of Legend of the Eight Samurai (1983)

Legend of the Eight Samurai, released in 1983, was directed by Kinji Fukasaku and features performances by Hiroko Yakushimaru, Sonny Chiba, Hiroyuki Sanada, Yuki Meguro, Masaki Kyômoto, Kenji Ôba, and Mari Natsuki. SYNOPSIS: A princess is pursued by a rival clan that has been annihilated and subsequently resurrected as demons. This film is inspired by the expansive 19th-century novel Nanso Satomi […]

Review of the Blu-ray Release of Legend of the Eight Samurai (1983)

Legend of the Eight Samurai, released in 1983, was directed by Kinji Fukasaku and features performances by Hiroko Yakushimaru, Sonny Chiba, Hiroyuki Sanada, Yuki Meguro, Masaki Kyômoto, Kenji Ôba, and Mari Natsuki. SYNOPSIS: A princess is pursued by a rival clan that has been annihilated and subsequently resurrected as demons. This film is inspired by the expansive 19th-century novel Nanso Satomi […]

Sharon Stone is set to appear in the upcoming season of Euphoria.

Acting legend Sharon Stone is familiar with intense situations in her career, but stepping into the realm of Euphoria could be her most adventurous role yet. According to THR, Stone is in discussions to join the series by Sam Levinson and HBO, which stars the award-winning Zendaya. Details about her potential role remain under wraps at this moment.

Sharon Stone is set to appear in the upcoming season of Euphoria.

Acting legend Sharon Stone is familiar with intense situations in her career, but stepping into the realm of Euphoria could be her most adventurous role yet. According to THR, Stone is in discussions to join the series by Sam Levinson and HBO, which stars the award-winning Zendaya. Details about her potential role remain under wraps at this moment.

Alien: Paradiso #3 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Marvel Comics will launch Alien: Paradiso #3 this Wednesday, and you can check out the official preview of the issue below… TSULA KANE CONFRONTS HER FATHER’S DESTINY: DEATH by XENO! Many years ago, Weyland-Yutani concealed Thomas Kane’s brutal death aboard the Nostromo, keeping the reality hidden even from his wife and child who […]

Alien: Paradiso #3 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Marvel Comics will launch Alien: Paradiso #3 this Wednesday, and you can check out the official preview of the issue below… TSULA KANE CONFRONTS HER FATHER’S DESTINY: DEATH by XENO! Many years ago, Weyland-Yutani concealed Thomas Kane’s brutal death aboard the Nostromo, keeping the reality hidden even from his wife and child who […]

David Lynch: The Significant Mystery of American Cinema

Simon Thompson delves into the legacy of the late, remarkable David Lynch. To begin this piece in the most straightforward manner, David Lynch, one of the most unique directors in American cinema, has passed away. Although I was aware that his health had sadly deteriorated since 2020, it still seems nearly unimaginable to come to terms with […]