Berlinale Review: All I Had Was Nothingness Complements Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah Flawlessly.

While reading Claude Lanzmann’s 2009 memoir The Patagonian Hare, director Guillaume Ribot was deeply inspired by insights concerning the creation of the monumental Shoah. The memoir discusses the making of Shoah in four chapters, illustrating Lanzmann’s investigative efforts to locate perpetrators and witnesses for interviews. Perhaps it was this investigative aspect that initially prompted Ribot to contemplate crafting a behind-the-scenes narrative. However, what truly elevates All I Had Was Nothingness as a compelling companion piece is its willingness to confront the most challenging questions emanating from the heavy silence surrounding the Holocaust; the inquiry into “why” looms hauntingly large.

With a background in photography and Holocaust memory, Ribot narrates the film utilizing Lanzmann’s own words, intertwined with archival footage that was not included in the final nine-hour installment of Shoah. The United States Holocaust Museum retains a total of 220 hours of raw footage (accessible online), from which Ribot extracted fragments to create what can be viewed as, if not a road movie, then a film reflecting on a journey. It serves as a meandering, self-reflexive account of Lanzmann’s own uncertainties and aspirations during the twelve years spent making the definitive film on the Holocaust.

All I Had Was Nothingness establishes its own storytelling rhythm without explicitly making a structural statement: some scenes are abruptly cut, only to be revisited later, for instance. Although Ribot's presence is almost non-existent (aside from his voice), Lanzmann is present in every frame. There are brief, B-roll clips of the director in contemplative silence, and sequences showcasing the landscapes of his travels (whether in Poland or New York), featuring sunrises, sunsets, and parks to allow viewers a moment to breathe before the subsequent interview. The documentary-detective approach also highlights Lanzmann’s challenges in financing his film and efforts to secure more funding.

Shoah is often regarded as a cinema landmark. While it undoubtedly holds that status, Ribot’s film also underscores Lanzmann’s persistent commitment to documenting oral histories of the Holocaust. All I Had Was Nothingness portrays him as a researcher grappling with ethical and moral dilemmas, as well as an empathetic individual whose candid conversations contributed to the film's impact. In one sequence, Lanzmann and his small crew are caught in the act, posing as historians while recording video without consent; in another, the camera focuses closely on a poignant emotional moment, capturing Lanzmann gently placing his hand over that of his interviewee.

“Shoah is the abolition of the distance between past and present,” Lanzmann’s words resonate at the film's conclusion. This notion also applies to trauma; it is not merely a “thing” but an embodied chronotope. A body retains memories, and in experiencing trauma, it can regress to the time and place of its origin. These reflections are not overtly articulated in All I Had Was Nothingness, which is beneficial: Lanzmann’s keen awareness of the significance of dialogue for victims and witnesses shaped his directorial choices to stage certain scenes or occasionally reenact events. The raw footage exudes anguish, and the film's creation keeps All I Had Was Nothingness shielded from negative critique. The film pays tribute to Lanzmann’s work with the utmost sincerity, yet it deserves a longer existence than merely serving as a token of German self-reflection at the Berlinale. In light of contemporary German politics and strict regulations regarding permissible discourse about Israel and Gaza, the bravery displayed by Lanzmann should not be confined to a Holocaust of the past.

All I Had Was Nothingness premiered at the 2025 Berlinale.

Other articles

Kristen Stewart and Alia Shawkat will star in The Wrong Girl.

Kristen Stewart (Love Lies Bleeding) and Alia Shawkat (Blink Twice) are starring in Dylan Meyer’s feature film debut, The Wrong Girl, which started filming in Los Angeles last week under the banner of Neon. The movie centers on "Frankie (Stewart) and Molly (Shawkat), dependent best friends navigating life from paycheck to paycheck and bong rip to bong rip, when a mix-up leads to [...]"

Kristen Stewart and Alia Shawkat will star in The Wrong Girl.

Kristen Stewart (Love Lies Bleeding) and Alia Shawkat (Blink Twice) are starring in Dylan Meyer’s feature film debut, The Wrong Girl, which started filming in Los Angeles last week under the banner of Neon. The movie centers on "Frankie (Stewart) and Molly (Shawkat), dependent best friends navigating life from paycheck to paycheck and bong rip to bong rip, when a mix-up leads to [...]"

Pet Shop Days Trailer: Olmo Schnabel’s Directorial Debut, Supported by Martin Scorsese, is Set to Hit Theaters This March.

Having premiered at the 2023 Venice Film Festival, Olmo Schnabel's directorial debut, Pet Shop Days, subsequently screened at the Chicago International Film Festival, SXSW, and others. This drama, supported by executive producers like Martin Scorsese, Jeremy O. Harris, and Michel Franco, is set to be released in theaters next month through Utopia.

Pet Shop Days Trailer: Olmo Schnabel’s Directorial Debut, Supported by Martin Scorsese, is Set to Hit Theaters This March.

Having premiered at the 2023 Venice Film Festival, Olmo Schnabel's directorial debut, Pet Shop Days, subsequently screened at the Chicago International Film Festival, SXSW, and others. This drama, supported by executive producers like Martin Scorsese, Jeremy O. Harris, and Michel Franco, is set to be released in theaters next month through Utopia.

Berlinale Review: Kontinental ’25 Demonstrates That Radu Jude Has No Further Proof to Offer

“The id becomes tiresome,” art critic Jackson Arn noted recently, “when it is allowed too much freedom of expression.” Romanian director Radu Jude keeps it restrained by anchoring his embellishments in stark normalcy. Toward the conclusion of Kontinental ’25, a former professor, Orsolya (Eszter Tompa), and her past student, Fred (Adonis Tanța), find themselves by a monument dedicated to the anti-communist resistance in

Berlinale Review: Kontinental ’25 Demonstrates That Radu Jude Has No Further Proof to Offer

“The id becomes tiresome,” art critic Jackson Arn noted recently, “when it is allowed too much freedom of expression.” Romanian director Radu Jude keeps it restrained by anchoring his embellishments in stark normalcy. Toward the conclusion of Kontinental ’25, a former professor, Orsolya (Eszter Tompa), and her past student, Fred (Adonis Tanța), find themselves by a monument dedicated to the anti-communist resistance in

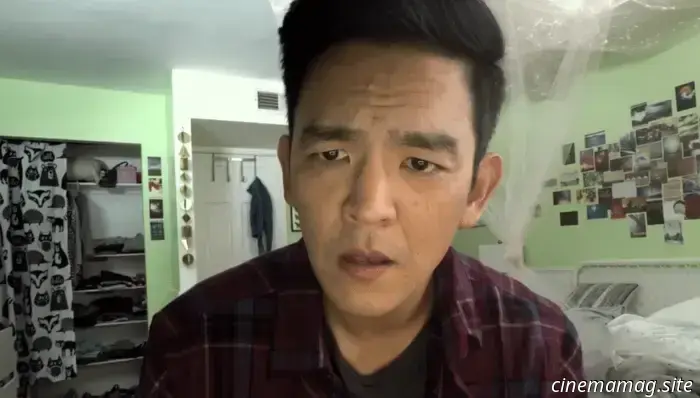

Season 2 of Poker Face introduces John Cho, Haley Joel Osment, Davionte Ganter, Patti Harrison, and Justin Theroux.

The second season of Rian Johnson's mystery comedy Poker Face on Peacock has revealed new guest stars. Joining the cast for the upcoming episodes are John Cho (Star Trek), Haley Joel Osment (Blink Twice), Davionte Ganter, known as the rapper GaTa, Patti Harrison (Trolls Band Together), and Justin Theroux (Beetlejuice Beetlejuice). Poker Face features […]

Season 2 of Poker Face introduces John Cho, Haley Joel Osment, Davionte Ganter, Patti Harrison, and Justin Theroux.

The second season of Rian Johnson's mystery comedy Poker Face on Peacock has revealed new guest stars. Joining the cast for the upcoming episodes are John Cho (Star Trek), Haley Joel Osment (Blink Twice), Davionte Ganter, known as the rapper GaTa, Patti Harrison (Trolls Band Together), and Justin Theroux (Beetlejuice Beetlejuice). Poker Face features […]

Spike Lee Reveals First Look at Highest 2 Lowest and Confirms Release for Summer 2025.

Spike Lee's significant year has already started notably at the Super Bowl with a connection to one of his most overlooked films. Now, the director is completing his first narrative feature in five years, which is expected to debut at Cannes. Titled Highest 2 Lowest, his reimagining of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, focuses on

Spike Lee Reveals First Look at Highest 2 Lowest and Confirms Release for Summer 2025.

Spike Lee's significant year has already started notably at the Super Bowl with a connection to one of his most overlooked films. Now, the director is completing his first narrative feature in five years, which is expected to debut at Cannes. Titled Highest 2 Lowest, his reimagining of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, focuses on

Berlinale Review: Timestamp Depicts a Tapestry of Suffering and Resilience Among Ukrainian Children

There are no images of conflict in Ukrainian director Kateryna Gornostai’s Timestamp, yet the profound impact of Russia's unjust invasion of her nation is evident in every expression and statement, alongside the immense devastation that remains. Filmed from March 2023 to June 2024, this poignant documentary captures the life-changing metamorphosis of school-age children.

Berlinale Review: Timestamp Depicts a Tapestry of Suffering and Resilience Among Ukrainian Children

There are no images of conflict in Ukrainian director Kateryna Gornostai’s Timestamp, yet the profound impact of Russia's unjust invasion of her nation is evident in every expression and statement, alongside the immense devastation that remains. Filmed from March 2023 to June 2024, this poignant documentary captures the life-changing metamorphosis of school-age children.

Berlinale Review: All I Had Was Nothingness Complements Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah Flawlessly.

While reading Claude Lanzmann’s 2009 memoir The Patagonian Hare, director Guillaume Ribot was inspired by the reflections on the creation of the significant film Shoah. The memoir discusses the production of Shoah in four of its chapters, detailing Lanzmann’s investigative efforts to locate perpetrators and witnesses and conduct interviews with them. Perhaps it was the investigative nature of this approach that