There’s Still Tomorrow: Director Paola Cortellesi Discusses Domestic Violence, International Success, and the Influence of Italian Neorealism

After years of acclaimed performances in Italian film and television, Paola Cortellesi has made her directorial debut with There’s Still Tomorrow, a post-war drama set in the 1940s that she also co-wrote and stars in. The film follows the matriarch of a working-class family as she deals with a toxic marriage and a daughter she wishes to shield from a similar fate, alongside her romantic dreams of a better life. This black-and-white film became a major box-office hit in Italy, ranking among the country’s top 10 highest-grossing films of all time.

In advance of the film’s U.S. release this Friday through Greenwich Entertainment, I spoke with Cortellesi about capturing the film's unique tone, the influence of classic Neorealist dramas and comedies, the central mother-daughter narrative, and why the film has struck a chord both in Italy and internationally.

The Film Stage: The film begins with a slap. How crucial was it to depict the dangers of Delia’s everyday life from the outset?

Paola Cortellesi: The opening scene serves as the opera's overture, summarizing key elements that will unfold throughout the film. It clearly presents violence, incorporating a touch of absurdity and even humor, as Delia behaves as if nothing has happened; it seems inconsequential. She's like a modern-day Cinderella. The contrasting music is a famous tune of the era: “I opened a window. And let’s breathe the fresh air of the spring.” Meanwhile, a dog is urinating in the basement. It’s a grim situation, but amusing in a way. This sets the stage for the themes to come.

You’ve mentioned being influenced by Italian Neorealism and comedies. Were there particular films you revisited while preparing, and how did they shape your process?

As Italians, we grew up surrounded by neorealism and the Italian comedies of the '50s and '60s. Since we watched them on television, they're ingrained in our culture. They certainly inspired me. Additionally, my grandmother’s stories play a significant role. It's a blend of their experiences, viewed through the lens of how cinema portrayed the era, specifically from the 1940s. I was particularly fond of a style known as “pink neorealism,” which depicts authentic moments and real conversations but adds a romantic touch, making it sweeter. I enjoy many films in that genre, including Campo de’ fiore [The Peddler and the Lady], and I could name many more, especially those featuring Anna Magnani, who was instrumental in pink neorealism.

That style of cinema heavily influenced my work. I opted for black-and-white to reflect my grandmother's memories of that time; it felt as if they were speaking to me that way. Thus, the black-and-white aesthetic was chosen intentionally. The film changes within the first eight-and-a-half minutes, mirroring neorealist techniques—using a square screen and music reminiscent of that period. While the opening might seem deceptive, it transforms completely from the title onwards: the music, composition, dialogue, and character interactions all evolve.

How did the collaboration with cinematographer Davide Leone unfold? The film is shot in black-and-white yet has a distinct desaturated look.

We filmed with standard color cameras, but I viewed the footage in black-and-white on the monitor. Naturally, it doesn’t exactly replicate what ends up on-screen. We made numerous adjustments, collaborating with the set and costume designers to differentiate colors between costumes and wallpaper, for example, since everything could have turned out gray. We aimed to create contrast on set, which was part of the process.

I loved the use of anachronistic music. Did you select these pieces early on as a way to indicate that these issues are still pertinent today?

Those musical choices were thoughtfully incorporated; certain scenes evolved directly from the music. I didn’t aim to mimic neorealism, as I wanted to express my own vision. While the subject of domestic violence is central, I chose to set the narrative in that era to speak about contemporary issues because we still grapple with domestic violence and femicide; on average, a woman is killed every 72 hours. My goal was to address the roots of this issue—not to suggest it began in the '30s, as it's a timeworn problem. Though Italy has evolved, that mindset remains pervasive. Returning to the music, it serves a dual purpose: it doesn’t merely reference the past but speaks to our current realities. I selected specific songs while writing.

The film beautifully evolves into a mother-daughter narrative. What was it like crafting that part of the story? Did you draw from your own experiences?

Yes, but not from a particular experience. I consider myself fortunate in comparison to the characters. This film is dedicated to my daughter; she is 12 now, but when I was writing

Otros artículos

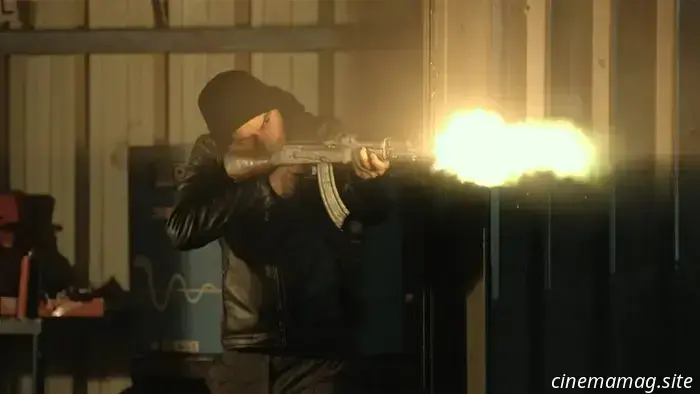

Tráiler Exclusivo en Estados Unidos del aclamado thriller francés The Temple Woods Gang, que llegará a Nueva York el 12 de marzo

Nombrada una de las 10 mejores películas de Cahiers du Cinéma en 2023, el thriller criminal de Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche, The Temple Woods Gang, finalmente tendrá un estreno adecuado en EE.UU. a finales de este año en varios Futuros. Sin embargo, el público de la ciudad de Nueva York tendrá la oportunidad de verlo la próxima semana como parte de una proyección especial

Tráiler Exclusivo en Estados Unidos del aclamado thriller francés The Temple Woods Gang, que llegará a Nueva York el 12 de marzo

Nombrada una de las 10 mejores películas de Cahiers du Cinéma en 2023, el thriller criminal de Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche, The Temple Woods Gang, finalmente tendrá un estreno adecuado en EE.UU. a finales de este año en varios Futuros. Sin embargo, el público de la ciudad de Nueva York tendrá la oportunidad de verlo la próxima semana como parte de una proyección especial

Vampirella #675-Avance del cómic

Dynamite Entertainment lanza Vampirella #675 este miércoles, y puedes ver la vista previa oficial a continuación Following Luego de los devastadores eventos de "The Dark World", el analista de Vampirella, Doc Chary, comparece ante una junta de revisión para explicar su " habilitación "del paracosmos inspirado en el"fetiche de vampiros" de Ella Normandy en este número especial de aniversario que marca un año desde la cuenta regresiva []]

Vampirella #675-Avance del cómic

Dynamite Entertainment lanza Vampirella #675 este miércoles, y puedes ver la vista previa oficial a continuación Following Luego de los devastadores eventos de "The Dark World", el analista de Vampirella, Doc Chary, comparece ante una junta de revisión para explicar su " habilitación "del paracosmos inspirado en el"fetiche de vampiros" de Ella Normandy en este número especial de aniversario que marca un año desde la cuenta regresiva []]

Paola Cortellesi, directora de There's Still Tomorrow, habla sobre la Violencia Doméstica, el Éxito Global y el Neorrealismo Italiano

Después de décadas de célebres actuaciones en el cine y la televisión italianos, Paola Cortellesi hizo su debut como directora con There's Still Tomorrow, un drama de posguerra ambientado en la década de 1940 que también coescribió y dirigió. Siguiendo a la matriarca de una familia de clase trabajadora que atraviesa un matrimonio tóxico y a una hija a la que no quiere seguir los mismos pasos, como

Paola Cortellesi, directora de There's Still Tomorrow, habla sobre la Violencia Doméstica, el Éxito Global y el Neorrealismo Italiano

Después de décadas de célebres actuaciones en el cine y la televisión italianos, Paola Cortellesi hizo su debut como directora con There's Still Tomorrow, un drama de posguerra ambientado en la década de 1940 que también coescribió y dirigió. Siguiendo a la matriarca de una familia de clase trabajadora que atraviesa un matrimonio tóxico y a una hija a la que no quiere seguir los mismos pasos, como

-Movie-Review.jpg) Mickey 17 (2025) - Reseña de la película

Micrófono 17, 2025. Dirigida por Bong Joon Ho. Está protagonizada por Robert Pattinson, Naomi Acmgnie, Marmgnie Ruffalo, Toni Collette, Anamaria Vartolomei, Steven Yeun, Patsy Ferran, Steve Parmgney, Tim Mggney, Holliday Grainger, Michael Monroe, Ed Muggard Davis, Cameron Britton, Ian Hanmore, Ellen Robertson, Rose Shalloo, Daniel Henshall, Angus Imrie y Anna Mouglalis. SINOPSIS: Micah Barnes, un "prescindible".

Mickey 17 (2025) - Reseña de la película

Micrófono 17, 2025. Dirigida por Bong Joon Ho. Está protagonizada por Robert Pattinson, Naomi Acmgnie, Marmgnie Ruffalo, Toni Collette, Anamaria Vartolomei, Steven Yeun, Patsy Ferran, Steve Parmgney, Tim Mggney, Holliday Grainger, Michael Monroe, Ed Muggard Davis, Cameron Britton, Ian Hanmore, Ellen Robertson, Rose Shalloo, Daniel Henshall, Angus Imrie y Anna Mouglalis. SINOPSIS: Micah Barnes, un "prescindible".

Reseña de The Rule of Jenny Pen: John Lithgow Atormenta a Geoffrey Rush en Depravado Horror psicológico

Tres décadas después del thriller psicológico alegremente desquiciado Raising Cain de Brian De Palma, John Lithgow ha encontrado una vez más un papel cinematográfico para mostrar su garbo por exudar maldad trastornada. La regla de Jenny Pen, del director neozelandés James Ashcroft, tras su Regreso a Casa en la oscuridad, seleccionado en Sundance, encuentra a Lithgow como Dave Crealy, un

Reseña de The Rule of Jenny Pen: John Lithgow Atormenta a Geoffrey Rush en Depravado Horror psicológico

Tres décadas después del thriller psicológico alegremente desquiciado Raising Cain de Brian De Palma, John Lithgow ha encontrado una vez más un papel cinematográfico para mostrar su garbo por exudar maldad trastornada. La regla de Jenny Pen, del director neozelandés James Ashcroft, tras su Regreso a Casa en la oscuridad, seleccionado en Sundance, encuentra a Lithgow como Dave Crealy, un

Keke Palmer, líder de The ' Burbs, agrega a Haley Joel Osment, RJ Cyler y más

Keke Palmer acaba de llevarse a casa el artista del Año en los NAACP Image Awards y continuará su buena racha con el próximo The ' Burbs. La nueva versión televisiva de la película de 1989 ve a Palmer a la cabeza con la incorporación de seis estrellas invitadas recurrentes a su elenco. Según Variety, Haley Joel Osment (El sexto sentido), []]

Keke Palmer, líder de The ' Burbs, agrega a Haley Joel Osment, RJ Cyler y más

Keke Palmer acaba de llevarse a casa el artista del Año en los NAACP Image Awards y continuará su buena racha con el próximo The ' Burbs. La nueva versión televisiva de la película de 1989 ve a Palmer a la cabeza con la incorporación de seis estrellas invitadas recurrentes a su elenco. Según Variety, Haley Joel Osment (El sexto sentido), []]

There’s Still Tomorrow: Director Paola Cortellesi Discusses Domestic Violence, International Success, and the Influence of Italian Neorealism

After years of acclaimed performances in Italian film and television, Paola Cortellesi made her directorial debut with There's Still Tomorrow, a post-war drama set in the 1940s that she also co-wrote and stars in. The story revolves around the matriarch of a working-class family as she deals with a troubled marriage and a daughter she hopes will not repeat her mistakes.