Bring Her Back Review: A Nerve-Wracking Success in Horror

Horror films that address grief are not a new phenomenon, yet it's hard to deny that this theme has been overused with diminishing returns over the past decade, weighing down even the most exploitative slashers. I suspect that twin brothers Danny and Michael Philippou––the YouTubers-turned-filmmakers behind the outstanding 2023 supernatural thriller Talk to Me––share these same concerns about the superficial use of a universally relatable theme that has permeated cinemas almost weekly. While their ambitious sophomore project Bring Her Back appears to delve into dark mysticism like their debut, it unveils itself as a direct commentary on the shallow exploitation of grief, drawing on the existential nihilism of French New Extremity films like Martyrs to illustrate how unhealthy it is to cope with death in such a superficial manner. Furthermore, its status as one of the most distressing and anxiety-inducing horror films in recent memory when taken at face value is merely an added bonus.

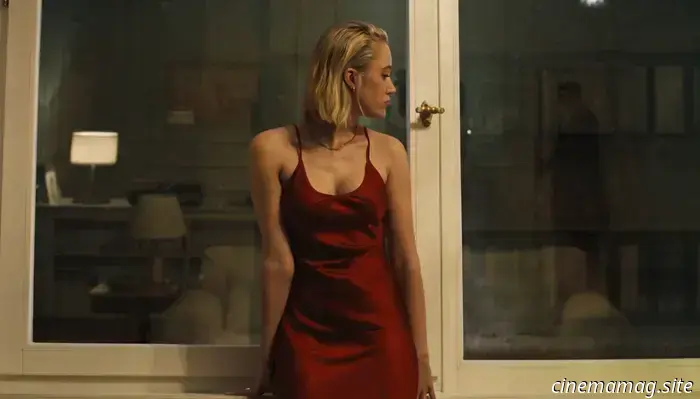

Following their father’s death, step-siblings Andy (Billy Barratt) and Piper (Sora Wong) are placed with a new foster parent, expecting it to be a three-month stay until Andy turns 18 and can seek guardianship. Instead, they find themselves living with Laura (Sally Hawkins), a former child therapist who seems unusually eager to dig into their past traumas—from Piper’s near-total blindness due to a childhood accident to Andy’s abuse at the hands of their father. With Laura still grappling with the loss of her daughter from many years ago and having a track record as a foster parent, the siblings initially overlook her eccentricities—until Andy cannot ignore the strange behavior of her other foster son, Oliver (Jonah Wren Phillips). Realizing she can drive a wedge between them, Laura seeks to depict Andy as an unreliable narrator to his blind sister, manipulating every aspect of his life to push him out entirely.

Going into further detail about Laura's schemes would risk revealing too much about the distinct horror territory the brothers explore, reducing an unlikely subgenre to its core and revitalizing it in the process. Instead, I’ll highlight the vividly rendered monster who doesn't hide in the shadows: Hawkins’ Laura is first portrayed as a troubled, unfiltered counterpart to her cheerful protagonist Poppy, but she descends into darker territory scene by scene. This comparison is not made lightly; it genuinely seems that the directors used that standout performance as a model, illustrating how someone filled with wonder and empathy can become jaded after facing challenges they cannot overcome, failing to recognize the sociopathic tendencies that emerge from their originally good intentions.

An opening sequence featuring Eastern European séances, depicted in grainy VHS footage, should foreshadow Laura’s unwholesome motivations long before the story allows for proper articulation of their relevance. Even beyond the most horror-centric moments, she remains a quietly frightening figure, struggling with an immature approach to dealing with death. Perhaps the most chilling scene is one grounded in domestic drama, where she pressures the two minors into becoming inebriated at a makeshift wake for their father, following a funeral where she chastises Andy for grieving in a way she deems unacceptable. This moment serves both as a turning point in revealing the characters’ relationships with deceased family members and as a meta-commentary on the influx of grief-driven horror films; while there is no singular way to grieve, recent films have often portrayed it in a formulaic manner. The boy grappling with his complex emotions is punished by a woman whose simplistic, almost childlike grieving has failed to confront the profound finality of death.

Piper’s disability—being blind in one eye and nearsighted in the other—is exploited by Laura throughout the story, yet although Piper’s limited perception drives the narrative, the filmmakers avoid using it as a simplistically reductive element. There are casual moments highlighting how her blindness affects daily activities, but these never paint her as a mere victim; she may be emotionally exploited, but it is the sinister foster parent, not her well-adapted condition, that endangers her autonomy. Her character is never defined by her blindness, even as it shapes her experiences, reflecting the directors’ humane approach despite putting their characters through harrowing situations.

While Bring Her Back presents a relentless and brutal experience, it never embraces nihilism for its own sake; the influence of French New Extremity is balanced with genuine compassion for the young protagonists. They may not shy away from challenging endurance and exhibit greater boldness than many horror filmmakers dealing with children in jeopardy, but it would be unfair to accuse them—unlike some in the same movement—of senselessly torturing characters without deeper significance. These influences can even extend to unexpected works—such as Michael Haneke’s Caché, mirrored in the portrayal of Oliver on Laura's farm and a central mystery involving illicit videotapes.

The Philippou brothers adeptly weave their inspirations into their film without making them blatantly obvious; they grasp that the best

Other articles

Peacock launches its 90 Minutes promotion with a poster and images for the football drama series.

Streaming service Peacock has unveiled a poster, trailer, and images for its upcoming soccer—apologies, can’t say it that way—football drama series 90 Minutes, which is set to premiere next week. Developed by Joe Rendon (Búnker), the series features José María De Tavira, Teresa Ruiz, Raul Méndez, Alvaro Guerrero, Adrián Vazquez, Pierre Louis, Diego Guzmán, and others.

Peacock launches its 90 Minutes promotion with a poster and images for the football drama series.

Streaming service Peacock has unveiled a poster, trailer, and images for its upcoming soccer—apologies, can’t say it that way—football drama series 90 Minutes, which is set to premiere next week. Developed by Joe Rendon (Búnker), the series features José María De Tavira, Teresa Ruiz, Raul Méndez, Alvaro Guerrero, Adrián Vazquez, Pierre Louis, Diego Guzmán, and others.

Maika Monroe is set to join the cast of Zachary Wigon's Victorian Psycho.

Zachary Wigon’s Victorian Psycho has secured its leading actress. Maika Monroe (Longlegs) will portray a murderous governess in the film, alongside Thomasin McKenzie (Last Night in Soho). Monroe takes on the part that Margaret Qualley from The Substance was previously attached to. This film is based on the best-selling novel by Virginia Feito, who also […]

Maika Monroe is set to join the cast of Zachary Wigon's Victorian Psycho.

Zachary Wigon’s Victorian Psycho has secured its leading actress. Maika Monroe (Longlegs) will portray a murderous governess in the film, alongside Thomasin McKenzie (Last Night in Soho). Monroe takes on the part that Margaret Qualley from The Substance was previously attached to. This film is based on the best-selling novel by Virginia Feito, who also […]

Trailer for The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire: Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich's Impressive Debut Set to Release in June

Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich's directorial debut is both mesmerizing and unsettling in its storytelling, and it was among my favorite finds at last year's New York Film Festival. This post-biopic focuses on Caribbean surrealist Suzanne Césaire and examines the challenge of adapting a real-life story for the screen. Cinema Guild has acquired it for release starting on June 6.

Trailer for The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire: Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich's Impressive Debut Set to Release in June

Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich's directorial debut is both mesmerizing and unsettling in its storytelling, and it was among my favorite finds at last year's New York Film Festival. This post-biopic focuses on Caribbean surrealist Suzanne Césaire and examines the challenge of adapting a real-life story for the screen. Cinema Guild has acquired it for release starting on June 6.

Batman and Robin: Year One #7 - Comic Book Teaser

Next week, DC Comics will launch Batman and Robin: Year One #7, and we have an exclusive early look at the official preview for the issue below. The General is searching for the individual behind the mask and is on a rampage. Meanwhile, the Dynamic Duo are pushing themselves to their limits and becoming exhausted as they work to stop […]

Batman and Robin: Year One #7 - Comic Book Teaser

Next week, DC Comics will launch Batman and Robin: Year One #7, and we have an exclusive early look at the official preview for the issue below. The General is searching for the individual behind the mask and is on a rampage. Meanwhile, the Dynamic Duo are pushing themselves to their limits and becoming exhausted as they work to stop […]

The indie slasher The Boatyard has released a trailer in anticipation of its digital launch in June.

In anticipation of its digital launch this June, Reel2Reel Films has unveiled a trailer for the indie slasher horror film The Boatyard, directed by Dale Stelly. The plot follows five college students who, after experiencing a breakdown in the middle of the ocean, accept assistance from a seemingly friendly stranger who offers to tow them to his boatyard, but they […]

The indie slasher The Boatyard has released a trailer in anticipation of its digital launch in June.

In anticipation of its digital launch this June, Reel2Reel Films has unveiled a trailer for the indie slasher horror film The Boatyard, directed by Dale Stelly. The plot follows five college students who, after experiencing a breakdown in the middle of the ocean, accept assistance from a seemingly friendly stranger who offers to tow them to his boatyard, but they […]

Star Wars: The High Republic Adventures #18 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Dark Horse Comics is set to release Star Wars: The High Republic Adventures #18 next week, and you can take a look at the official preview of the issue below. The Battle of Eriadu reaches a thrilling climax! Jedi Knight Farzala Tarabal guides his brave companions into a decisive battle against the Nihil, putting everything on the line […]

Star Wars: The High Republic Adventures #18 - Comic Book Sneak Peek

Dark Horse Comics is set to release Star Wars: The High Republic Adventures #18 next week, and you can take a look at the official preview of the issue below. The Battle of Eriadu reaches a thrilling climax! Jedi Knight Farzala Tarabal guides his brave companions into a decisive battle against the Nihil, putting everything on the line […]

Bring Her Back Review: A Nerve-Wracking Success in Horror

Horror films that directly address grief are not a new phenomenon, but it’s hard to dispute that this theme has been increasingly overused in the last decade, often resulting in less fulfilling outcomes, even within the most superficial slasher films. I have strong suspicions about twin brothers Danny and Michael Philippou—who have transitioned from YouTubers to influential figures in cinema.