Cannes Review: Harris Dickinson's Urchin is a Reflective and Bold Directorial Premiere

A few scenes into Urchin, we journey through the Bardo. Initially, the camera (as seen in countless films before) zooms in on a shower drain, but then introduces something different: a tunnel filled with darkness and color that transitions to a damp, mossy tranquility, where a solitary man in a clearing, facing away from us, basks in the light. This bold sequence is directed by Harris Dickinson, who has managed to find the time—amidst his ascent as a beloved actor and sex symbol, as well as portraying John Lennon—to helm a reflective, adventurous film.

The transition from actor to director is often more lined with cautionary tales than with success stories. Cannes seems to take a particular, nearly sadistic pleasure in highlighting this journey—the potential for hubris undoubtedly attracts attention. Throughout all my visits to this festival, I’ve never witnessed a scene as undignified as the one outside the press screening for Ryan Gosling’s Lost River, a film that, for all practical purposes, appears to have vanished. It’s not surprising that such changes occur: if these individuals spend their professional lives being directed, why wouldn’t they explore directing themselves?

Challenges often arise in deciding which influences to adopt. Some (like Greta Gerwig or Paul Dano) seize the chance to provide actors and peers the space that they, perhaps, have not always received. Meanwhile, the works of actor-directors sometimes come across as a blend of styles from filmmakers they’ve either collaborated with or admired. In Urchin, Dickinson merges socially relevant realism (a British tradition) with the more contemporary aesthetic of a Safdie film: featuring medium shots, authentic streets, non-professionals, and occasional ventures down a vibrant drain. While these elements might not always mesh seamlessly (the film is inconsistent at its best), it presents a fascinating blend that conveys a clear political viewpoint.

Dickinson’s decisions have consistently been intriguing. It’s particularly revealing that since his breakout in Eliza Hittman’s Beach Rats—despite not being his most recognized lead performance—he appears to prefer remaining in the background, acting as a character actor with the allure and charm of a leading man. This inclination is evident in Urchin, where he takes on a small supporting role, reportedly stepping in only after another actor withdrew. This modesty extends to the mise-en-scène, which doesn’t attempt to recreate, for instance, the social satire of a Ruben Östlund. The film most akin to Dickinson’s work is likely Charlotte Regan’s Scrapper—financially, it is the smallest project he has undertaken in recent years.

Instead, Dickinson draws from his own experiences, particularly his upbringing in East London and his time in the service industry. Frank Dillane portrays Mike, a young man struggling with homelessness and drug addiction who ends up in jail after violently assaulting and robbing an innocent bystander attempting to assist him. Upon his release, now a few months sober, he begins his rehabilitation by working as a commis chef at a hotel restaurant, quickly forming friendships with coworkers until the job’s stresses plunge him into turmoil. Later, while collecting trash, he encounters a free-spirited woman named Andrea (Megan Northam), and they establish a close bond. Throughout, Dickinson allows Mike a few fleeting moments of release: first in a karaoke booth (singing Atomic Kitten) and later, more viscerally, while high on K at a performance venue.

There’s little here that feels entirely new, and some elements we’ve likely seen more frequently than we’d prefer, yet Dickinson merits recognition for utilizing such a familiar framework to comment on homelessness in the UK and the complications of the welfare system while also showcasing his actor—Dillane has strong presence and sharp comic timing, though he may be a bit too handsome for his role (I can think of several high-street fashion brands that would hire him, even if disheveled)—while exercising his own creative talents in the process. Although the shower drain serves as Urchin’s standout moment, there are several other sequences that surprised me—especially the abbey floor that appears to pull Mike towards it, tossing him around like a rag doll. If the 28-year-old Dickinson ever finds the opportunity to create another feature, I would be eagerly watching.

Urchin made its debut at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

Other articles

Elle Fanning plays the role of young Effie Trinket in The Hunger Games: Sunrise on the Reaping.

Lionsgate's forthcoming prequel, The Hunger Games: Sunrise on the Reaping, will feature a familiar character reappearing in a younger version. Elle Fanning (A Complete Unknown) is set to portray Effie Trinket, a role originally played by Elizabeth Banks in the earlier films. Effie served as the escort for the tributes from District 12, randomly drawing their names and accompanying them to the […]

Elle Fanning plays the role of young Effie Trinket in The Hunger Games: Sunrise on the Reaping.

Lionsgate's forthcoming prequel, The Hunger Games: Sunrise on the Reaping, will feature a familiar character reappearing in a younger version. Elle Fanning (A Complete Unknown) is set to portray Effie Trinket, a role originally played by Elizabeth Banks in the earlier films. Effie served as the escort for the tributes from District 12, randomly drawing their names and accompanying them to the […]

The trailer for season 2 of FUBAR features Arnold Schwarzenegger facing off against Carrie-Anne Moss.

Netflix has released a trailer, poster, and images for the second season of the action-comedy series FUBAR. In this season, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s seasoned CIA operative Luke Brunner and his team confront Greta Nelso (Carrie-Anne Moss), a German spy and former love from his past, who has returned with a scheme that poses a threat to […]

The trailer for season 2 of FUBAR features Arnold Schwarzenegger facing off against Carrie-Anne Moss.

Netflix has released a trailer, poster, and images for the second season of the action-comedy series FUBAR. In this season, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s seasoned CIA operative Luke Brunner and his team confront Greta Nelso (Carrie-Anne Moss), a German spy and former love from his past, who has returned with a scheme that poses a threat to […]

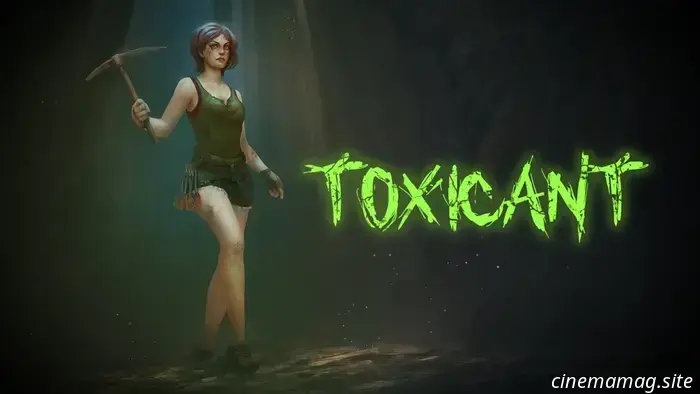

The roguelite survival horror game Toxicant is getting a significant update.

Indie developer Cosmocat Games is set to launch a significant free update for their roguelite survival horror game, Toxicant, on May 26th. The Rampage! Update features a completely new game mode for players to challenge their abilities, along with a new weapon designed to assist in tricky scenarios. Check out the new trailer below to find out what’s on the way […]

The roguelite survival horror game Toxicant is getting a significant update.

Indie developer Cosmocat Games is set to launch a significant free update for their roguelite survival horror game, Toxicant, on May 26th. The Rampage! Update features a completely new game mode for players to challenge their abilities, along with a new weapon designed to assist in tricky scenarios. Check out the new trailer below to find out what’s on the way […]

Cannes Review: Harris Dickinson's Urchin is a Reflective and Bold Directorial Premiere

A short while into Urchin, we embark on a journey through the Bardo. Initially, the camera focuses on a shower drain, reminiscent of countless films that came before it, but then introduces something fresh: a tunnel filled with darkness and color that opens up to a damp, mossy serenity, where a solitary man stands in a clearing.