“Images Are No More”: Oliver Laxe Discusses Sirāt and the Essence of Spirituality

As music reverberates through the desert terrain of Morocco's Atlas Mountains and ravers lose themselves in the incessant bass, murmurs of World War III linger in the background. In Sirāt, Oliver Laxe’s fourth feature, trying to pinpoint the external conflict beyond the mountains would be akin to missing the larger picture. The journey, or “Sirāt” as it is known, embodies the act of letting go—of the material and the physical—and, in turn, joining one's consciousness with the broader world and its inhabitants.

Having previously explored the Atlas Mountains in his second film, Mimosas, Laxe returns with what some have characterized as his interpretation of The Wages of Fear. When he learns that his missing daughter will be attending the rave, a father (Sergi Lopez) arrives seeking her. As a military group drives the attendees away, a group of friends breaks away to search for another rave deeper in the mountains. The father and his son join them, embarking on a perilous journey that tests their physical and mental strength. While comparisons to Clouzot's classic or Friedkin’s remake, Sorcerer, are indeed fitting, they remain somewhat superficial. Laxe’s quest is fundamentally spiritual.

As with all his works, Sirāt, named for a bridge mentioned in the Quran that spans from hell to paradise, reflects Laxe’s own spiritual odyssey. He channels his inquiries about faith through an exploration of the people and their surroundings. As the group makes its way across the desert, the landscape begins to resist them. Is this a consequence of the wars raging in the real world? Is it the land retaliating against a mainly white group encroaching on territory that is not theirs? Or is it merely a harsh terrain that no one should be reckless enough to traverse? Laxe leaves these questions open to interpretation, concentrating instead on how individuals might redirect their faith towards one another and summon the will to endure.

Laxe is a visually-oriented filmmaker, and Sirāt stands as his most abstract work to date. By taking his distinctive voice and applying it to a more mainstream approach, with clear influences from Mad Max, the film is an enchanting rush of bodies and beats. Significant portions of Sirāt unfold without dialogue, allowing audiences to immerse themselves in the director’s profound admiration for nature and his frustration at its exploitation, particularly in a region marked by colonialism.

During Sirāt’s showing at the New York Film Festival, I had a conversation with Laxe about the film, spirituality, and remaining grounded in an increasingly fractured world.

The Film Stage: This is your largest film to date, embracing what could be considered blockbuster or mainstream elements. In some of the Q&As, you mentioned your effort to create a more accessible film with Sirāt. Can you share how you balance that aspiration with maintaining your artistic voice?

Oliver Laxe: That was definitely a risk. There is a sense of service in my cinema; I truly want my films to reach an audience. One of my goals was to plant a seed in the minds of mainstream viewers, especially those who may not typically watch films of this nature. I aimed particularly toward a younger audience. I was 20 when I discovered films with depth, which profoundly impacted me.

Back then, I was emotionally distant, and cinema provided warmth to my soul, revealing to me that I possessed one. I wanted to create a similar experience for someone undergoing that journey now. I believe in cinema, I believe in images, and I appreciate popular and genre cinema, particularly American genre films. They’re part of my cultural landscape, and I have faith in the audience. It’s all about trusting that images can affect human perception and linger in memory. To me, cinema revolves around proportions, geometry, and a kind of spiritual geometry. An image is an enigmatic entity.

Spirituality is a consistent theme in your work, and here, it reveals itself through the act of dancing. How familiar were you with rave culture prior to making this film?

I frequently attended raves in France, Morocco, Spain, and Portugal. I enjoy dancing and electronic music, and I feel a sense of belonging to this community. I wouldn’t classify myself as a raver; I’m an artist. I maintain a certain distance from reality, unfortunately. For me, it was essential to use my body for expression. Raving enables me to release my energy and, more importantly, confront my wounds and scars. It’s fascinating because on the dance floor, you connect with both your strength and your fragility. Your body retains memories of your wounds, allowing you to connect with your inner child, the abandoned child, and the pain carried by your ancestors. You tap into your subconscious and the collective unconscious.

Being in a rave, surrounded by people sharing the same experience, feels powerful. Cinema operates similarly; in a theater, we sit in the dark without familial ties to those around us yet there exists a subtle,

Other articles

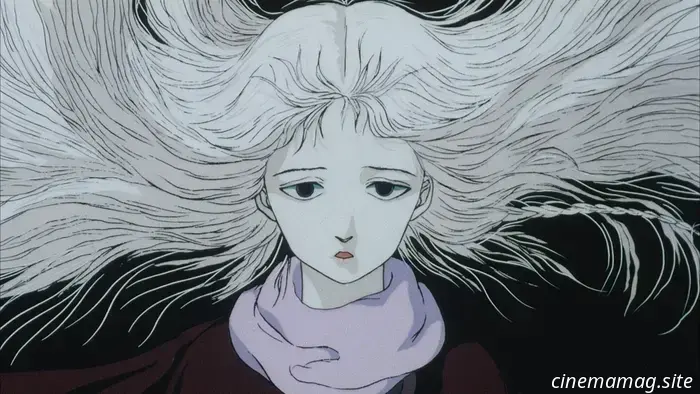

Mamoru Oshii's Angel's Egg is a radical and ethereal anime that stands out from the rest.

To effectively elucidate Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg—a stoic and ethereal cinematic journey renowned among anime and cult fans for its elusive nature, and one that more often evokes parallels with Cocteau, Tarkovsky, and Jodorowsky than with other anime—it is essential to discuss Rumiko Takahashi. Takahashi is best known in the West for her massive success.

Mamoru Oshii's Angel's Egg is a radical and ethereal anime that stands out from the rest.

To effectively elucidate Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg—a stoic and ethereal cinematic journey renowned among anime and cult fans for its elusive nature, and one that more often evokes parallels with Cocteau, Tarkovsky, and Jodorowsky than with other anime—it is essential to discuss Rumiko Takahashi. Takahashi is best known in the West for her massive success.

Idris Elba and Ruth Wilson are set to reprise their roles in the upcoming Luther film.

John Luther is set to return for a new feature film on Netflix, with Idris Elba reprising his famous role. He will once again be joined by Dermot Crowley as DCI Martin Schenk and Ruth Wilson...

Idris Elba and Ruth Wilson are set to reprise their roles in the upcoming Luther film.

John Luther is set to return for a new feature film on Netflix, with Idris Elba reprising his famous role. He will once again be joined by Dermot Crowley as DCI Martin Schenk and Ruth Wilson...

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

A new trailer for The Housemaid featuring Sydney Sweeney and Amanda Seyfried has been released.

Lionsgate has unveiled a new trailer for director Paul Feig’s forthcoming adaptation of Freida McFadden’s popular novel, The Housemaid. The thriller centers around Millie (Sydney Sweeney), a young woman...

A new trailer for The Housemaid featuring Sydney Sweeney and Amanda Seyfried has been released.

Lionsgate has unveiled a new trailer for director Paul Feig’s forthcoming adaptation of Freida McFadden’s popular novel, The Housemaid. The thriller centers around Millie (Sydney Sweeney), a young woman...

The last season of Outlander, which spans past, present, and future, is set to start in March.

The highly awaited eighth and final season of Starz's Outlander has revealed its premiere date as March 6th, 2026, marking the start of the end for the historical romance fantasy series. Out…

The last season of Outlander, which spans past, present, and future, is set to start in March.

The highly awaited eighth and final season of Starz's Outlander has revealed its premiere date as March 6th, 2026, marking the start of the end for the historical romance fantasy series. Out…

“Images Are No More”: Oliver Laxe Discusses Sirāt and the Essence of Spirituality

As music pulsates throughout the desert terrain of Morocco's Atlas Mountains and party-goers immerse themselves in the relentless bass, murmurs of World War III linger in the background. In Sirāt, the fourth feature by Oliver Laxe, trying to identify the specific external conflict beyond the mountain walls would mean overlooking the bigger picture.