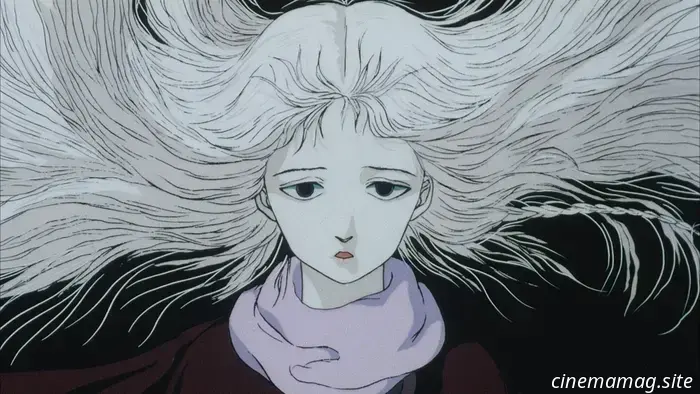

Mamoru Oshii's Angel's Egg is a radical and ethereal anime that stands out from the rest.

To effectively articulate the essence of Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg––an introspective, otherworldly cinematic exploration known for its resistance to explanation and often compared to the works of Cocteau, Tarkovsky, and Jodorowsky––it is essential to discuss Rumiko Takahashi. Takahashi, widely recognized in the West for her blockbuster manga Ranma ½ and Inuyasha along with their lengthy anime adaptations, is the best-selling female comic creator globally, a singular cultural phenomenon who has consistently published weekly serials for nearly fifty years. Central to her success is her talent for characterization: behind her quintessential characters’ soft and rounded designs, idealized physiques, and large expressive eyes lie vividly exaggerated egos and desires that frequently collide with one another, providing a cacophony of conflict week after week. Takahashi utilizes urban fantasy and screwball comedy to create insightful observations on love, gender, family, and tradition. Her output transcends boundaries as audiences of various ages, genders, and nationalities find reflections of their own emotions and quirks in the petty rivalries, unreciprocated affections, and tumultuous relationships that form the backbone of her fantastical settings––which uniquely blend sitcom elements with folklore––even as she often appears reluctant to advance central narratives.

Mamoru Oshii delineates “character, story, worldview” as the creative hierarchies of anime production, and mass entertainment in general, in that order. When Oshii landed his first major role as a young director by adapting Takahashi's inaugural hit Urusei Yatsura for television, he was initially constrained by these principles, reflected in his 1983 debut feature, Urusei Yatsura: Only You––a vibrant, colorful showcase for the anime’s broad cast, which Takahashi herself regards as her favorite of the eventual six films based on the series. With the sequel Beautiful Dreamer released the following year, however, Oshii was empowered to break free. Capitalizing on the audience's familiarity with the characters, he crafted an unusually surrealist comedy that shifted focus from the series' frenetic humor and romantic plots to a more introspective, even subversive tone. Through a multi-perspective mystery framework, Beautiful Dreamer reveals to the cast of Urusei Yatsura that they are ensnared in a single character’s dream world, wherein gravity, perspective, and time cease to function, and the same day––the day preceding the high school festival––repeats indefinitely. As the characters persist in their self-satisfied routines, the external world seems to evaporate while the town––aside from its pivotal locations, the protagonist’s home and school––starts to decay. Characters ponder the essence of dreams versus reality, as lingering shots of dilapidated or otherworldly urban landscapes unfold, turning water puddles into gravity-defying portals, and supporting characters gradually disappear. The film poses the question: how long before the dreamer's desires can no longer sustain the world? And who is truly the dreamer?

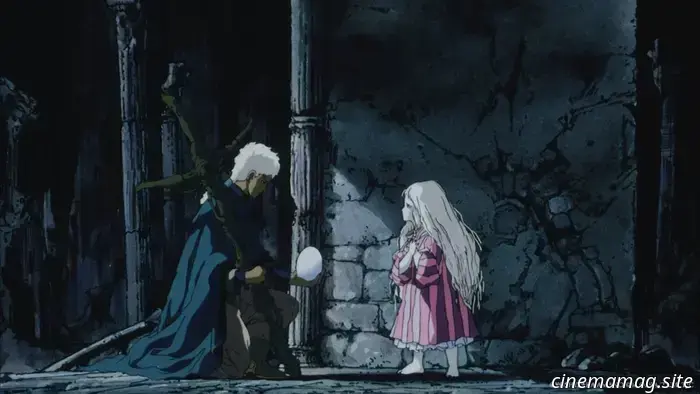

Oshii characterizes this as an inversion of “character, story, worldview”: prioritizing world and themes first, character last, subtly critiquing his own popular series. Both audiences and Rumiko Takahashi reacted against it at the time; Oshii soon found himself permanently detached from the Urusei Yatsura franchise. Unfazed, his next significant endeavor, the direct-to-video project Angel’s Egg, would adopt the “world, story, character” model, building a world and characters from the ground up (an early suggestion to spin it off from the Lupin III series was abandoned). This decision would lead to the creation of one of the most avant-garde works in the realm of Japanese animation.

In collaboration with illustrator Yoshitaka Amano––renowned for his gothic fantasy and steampunk art, particularly in Final Fantasy and Vampire Hunter D––Angel’s Egg is wholly focused on constructing a somber, dreamlike, and allegorical world through enigmatic imagery and contemplative silence. Oshii utilizes this visually rich world to forge meaning within a stark spiritual fable, markedly different from his subsequent films, yet containing the philosophical keys to nearly all of them.

The desolate, breezy realm of Angel’s Egg is characterized by a lack of names and limited utility of language. Existing between a primordial fairy tale and apocalyptic prophecy, its visual elements evoke the history of our world, while remaining unanchored in time and place as we recognize them. At the apex of this world, embryonic bird-like creatures rest within enormous translucent eggs, their eye movements accompanied by church bells and a trembling, dissonant choir. A mechanical sun––a spherical flying fortress that resembles a colossal turquoise eye––carries countless rows of human statues reminiscent of the Terracotta Army beneath a crimson sky; upon landing on a checker-patterned pathway that appears to stretch endlessly into the horizon, the

Other articles

Idris Elba and Ruth Wilson are set to reprise their roles in the upcoming Luther film.

John Luther is set to return for a new feature film on Netflix, with Idris Elba reprising his famous role. He will once again be joined by Dermot Crowley as DCI Martin Schenk and Ruth Wilson...

Idris Elba and Ruth Wilson are set to reprise their roles in the upcoming Luther film.

John Luther is set to return for a new feature film on Netflix, with Idris Elba reprising his famous role. He will once again be joined by Dermot Crowley as DCI Martin Schenk and Ruth Wilson...

The last season of Outlander, which spans past, present, and future, is set to start in March.

The highly awaited eighth and final season of Starz's Outlander has revealed its premiere date as March 6th, 2026, marking the start of the end for the historical romance fantasy series. Out…

The last season of Outlander, which spans past, present, and future, is set to start in March.

The highly awaited eighth and final season of Starz's Outlander has revealed its premiere date as March 6th, 2026, marking the start of the end for the historical romance fantasy series. Out…

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

Alien: Earth has been renewed for a second season.

A new trailer for The Housemaid featuring Sydney Sweeney and Amanda Seyfried has been released.

Lionsgate has unveiled a new trailer for director Paul Feig’s forthcoming adaptation of Freida McFadden’s popular novel, The Housemaid. The thriller centers around Millie (Sydney Sweeney), a young woman...

A new trailer for The Housemaid featuring Sydney Sweeney and Amanda Seyfried has been released.

Lionsgate has unveiled a new trailer for director Paul Feig’s forthcoming adaptation of Freida McFadden’s popular novel, The Housemaid. The thriller centers around Millie (Sydney Sweeney), a young woman...

“Images Are No More”: Oliver Laxe Discusses Sirāt and the Essence of Spirituality

As music pulsates throughout the desert terrain of Morocco's Atlas Mountains and party-goers immerse themselves in the relentless bass, murmurs of World War III linger in the background. In Sirāt, the fourth feature by Oliver Laxe, trying to identify the specific external conflict beyond the mountain walls would mean overlooking the bigger picture.

“Images Are No More”: Oliver Laxe Discusses Sirāt and the Essence of Spirituality

As music pulsates throughout the desert terrain of Morocco's Atlas Mountains and party-goers immerse themselves in the relentless bass, murmurs of World War III linger in the background. In Sirāt, the fourth feature by Oliver Laxe, trying to identify the specific external conflict beyond the mountain walls would mean overlooking the bigger picture.

Mamoru Oshii's Angel's Egg is a radical and ethereal anime that stands out from the rest.

To effectively elucidate Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg—a stoic and ethereal cinematic journey renowned among anime and cult fans for its elusive nature, and one that more often evokes parallels with Cocteau, Tarkovsky, and Jodorowsky than with other anime—it is essential to discuss Rumiko Takahashi. Takahashi is best known in the West for her massive success.