Mickey 17 Review: Bong Joon Ho’s Sci-Fi Comedy is a Strangely Manipulative, Self-Aware Allegory

Is Mark Ruffalo channeling Trump? Early in Bong Joon Ho’s Mickey 17, Ruffalo strides into the frame wearing a plush blazer, accompanied by his wife Ylfa (Toni Collette), basking in the applause of a crowd as if he were a messianic figure. Ruffalo plays Kenneth Marshall, the leader of a cult-like Church and former presidential candidate who is behind a new space mission aimed at relocating humanity from a nearly unlivable Earth to Niflheim, a distant planet. As a hopeless narcissist flanked by sycophants armed with cameras capturing his every move, he always has his impossibly white teeth on display in a self-satisfied grin, nostrils flared, with exaggerated vowel sounds. In a film that features not one but two Robert Pattinsons, it’s Ruffalo who captures the spotlight. If his speech and mannerisms jolted memories of another real-life narcissist surrounded by his own cadre of flatterers, that realization was more enlightening than distracting.

Bong's films have consistently engaged with significant issues in our culture, intertwining environmental disasters with narratives of inequality (as seen in Okja or Snowpiercer). However, this latest work addresses our current dire circumstances in ways that may surpass previous films; set in 2054, its language and concerns resonate strongly with our troubled 2020s. While not inherently a negative aspect, the film's critiques of exploitative capitalism and its jabs at the erratic tech moguls we have elevated to messiah status feel somewhat simplistic, even manipulative.

Based on Edward Ashton’s 2022 novel Mickey7, this is also Bong’s first outing as a sole writer, yet it retains a tendency for heavy exposition reminiscent of Snowpiercer, similarly shot by Darius Khondji in a wintry, snow-covered setting. Niflheim bears a striking resemblance to the glacial landscape traversed by Chris Evans’ character in that earlier film, and the basic plot structure is similar. At its core, Mickey 17 depicts a popular uprising against the ruling powers. However, the film presents an abundance of ideas, conspiracies, and subplots that require considerable effort to unpack. Notably, Bong reveals the most significant alteration to the source material through the film's title; when asked about it at the Berlinale, he jokingly remarked that seven “was not enough,” implying that if dying is a part of the job, it should be routine. The employee-martyr in question is Pattinson’s Mickey Barnes, a minor entrepreneur who, pursued by a ruthless loan shark, volunteers for the unforgiving tasks on Ruffalo’s spacecraft—an enormous vessel where the elite enjoy luxurious living spaces while workers reside in sparsely furnished dormitories, feasting on food with an unclear origin. Perhaps that’s for the best. The socioeconomic disparities illustrated through Fiona Crombie’s production design closely mirror those in Snowpiercer, with recurring Bong themes of class struggle, resource scarcity, and unappetizing food.

Mickey is labeled an “expendable,” meaning he can be killed and “printed” back to life in about 20 hours while his memory is securely stored in a device that resembles both a hard drive and a literal brick. This blend of anachronistic elements is something Bong has previously experimented with in Snowpiercer. If that film’s steampunk technology evoked Brazil, there are moments here where the wire-laden masks Mickey dons in the spaceship’s labs reminded me of La Jetée. This is because Mickey 17 is rich with real-world references and nods to sci-fi classics, including tributes to Gilliam and Marker, along with a Wilhelm Scream for good measure.

Nevertheless, the film’s most intriguing concepts—its exploration of the ethics surrounding expendables, the sociopaths overseeing these experiments, and the “meaning and terror of finality” as articulated ominously by Marshall—are strangely dismissed as either too complex to address or too clear to explore. Pattinson’s voiceover trivializes the mind-boggling technology producing doppelgängers with “It’s some crazy technology man; let’s just say it’s advanced,” while the film glosses over the chaos that likely followed such a horrific innovation with a dismissive “ethical fights and religious blah blah.”

This hasty handling is especially surprising given that the film introduces new twists and epiphanies, each accompanied by their own exposition-heavy backstory, such as when Mickey confronts another version of himself (Mickey18) mistakenly created under the belief that Mickey17 had perished on Niflheim. While they aren't the first “multiples,” it raises the question of why Mickey is the only expendable on a mission that Marshall insists is humanity’s greatest adventure.

Bong seems less interested in unraveling these intricacies than in presenting a story that resonates as a 21st-century parable of outcasts, lunatic plut

Other articles

Deadpool celebrates April Fool's Day with special Marvel variant covers.

Marvel has revealed that Deadpool will celebrate April Fool's Day with a series of variant covers featuring the Merc with a Mouth engaging in various pranks, jokes, fake advertisements, and irreverent tributes across seven of the publisher’s titles in March and April. Take a look at them here… Available 3/19 […]

Deadpool celebrates April Fool's Day with special Marvel variant covers.

Marvel has revealed that Deadpool will celebrate April Fool's Day with a series of variant covers featuring the Merc with a Mouth engaging in various pranks, jokes, fake advertisements, and irreverent tributes across seven of the publisher’s titles in March and April. Take a look at them here… Available 3/19 […]

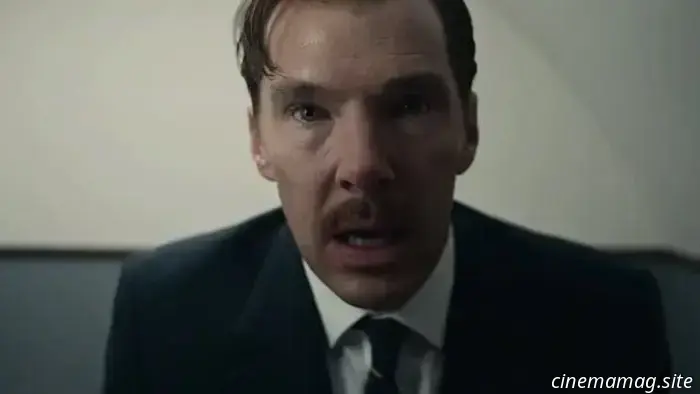

Benedict Cumberbatch taking over Tom Hardy's role in Blood on Snow.

Benedict Cumberbatch is now part of Blood on Snow, as reported by THR, indicating that the actor will take on a role originally intended for Tom Hardy. Aaron Taylor-Johnson takes the lead in Cary Fukunaga’s crime thriller, which is the director of No Time To Die, alongside Cumberbatch, Eva Green, Emma Laird, and Ben Mendelsohn. Taylor-Johnson portrays a hitman and fixer named Olav, who is […]

Benedict Cumberbatch taking over Tom Hardy's role in Blood on Snow.

Benedict Cumberbatch is now part of Blood on Snow, as reported by THR, indicating that the actor will take on a role originally intended for Tom Hardy. Aaron Taylor-Johnson takes the lead in Cary Fukunaga’s crime thriller, which is the director of No Time To Die, alongside Cumberbatch, Eva Green, Emma Laird, and Ben Mendelsohn. Taylor-Johnson portrays a hitman and fixer named Olav, who is […]

Eminem as a presidential candidate?

Eminem for president? This intriguing and imaginative idea for addressing the challenges faced by the Democrats has been proposed by New Yorker writer Jay Caspian Kang in the most recent edition.

Eminem as a presidential candidate?

Eminem for president? This intriguing and imaginative idea for addressing the challenges faced by the Democrats has been proposed by New Yorker writer Jay Caspian Kang in the most recent edition.

Christopher Eccleston and Billie Piper are set to reprise their roles in new Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor Adventures from Big Finish.

In 2005, Christopher Eccleston and Billie Piper attracted a new wave of Doctor Who enthusiasts to experience his adventures across time and space. This August, with the help of Big Finish Productions, the Ninth Doctor and Rose will return in a new twelve-part series titled Doctor Who – The Ninth Doctor Adventures, and these are […]

Christopher Eccleston and Billie Piper are set to reprise their roles in new Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor Adventures from Big Finish.

In 2005, Christopher Eccleston and Billie Piper attracted a new wave of Doctor Who enthusiasts to experience his adventures across time and space. This August, with the help of Big Finish Productions, the Ninth Doctor and Rose will return in a new twelve-part series titled Doctor Who – The Ninth Doctor Adventures, and these are […]

Dungeons & Dragons: The Forgotten Realms series is being developed by Netflix, with Shawn Levy from Stranger Things involved.

Netflix is preparing to invest in a new high-budget fantasy series, as Deadline reports that the streaming platform has enlisted Stranger Things executive producer and Deadpool & Wolverine director Shawn Levy to create a live-action Dungeons & Dragons series. Titled Dungeons & Dragons: The Forgotten Realms, the prospective series will be set in the […]

Dungeons & Dragons: The Forgotten Realms series is being developed by Netflix, with Shawn Levy from Stranger Things involved.

Netflix is preparing to invest in a new high-budget fantasy series, as Deadline reports that the streaming platform has enlisted Stranger Things executive producer and Deadpool & Wolverine director Shawn Levy to create a live-action Dungeons & Dragons series. Titled Dungeons & Dragons: The Forgotten Realms, the prospective series will be set in the […]

Berlinale Review: Hot Milk Provides a Wonderful Exploration of Maternal Trauma

The relationship between a mother and daughter is seldom portrayed as a love story, especially not in the manner that art has usually depicted it. While it is true that a mother feels a profound love for her daughter (and vice-versa), this affection is characterized by complexity and frequently intertwined with feelings of resentment. Deborah Levy, a British author, addresses this in her 2016 novel Hot Milk.

Berlinale Review: Hot Milk Provides a Wonderful Exploration of Maternal Trauma

The relationship between a mother and daughter is seldom portrayed as a love story, especially not in the manner that art has usually depicted it. While it is true that a mother feels a profound love for her daughter (and vice-versa), this affection is characterized by complexity and frequently intertwined with feelings of resentment. Deborah Levy, a British author, addresses this in her 2016 novel Hot Milk.

Mickey 17 Review: Bong Joon Ho’s Sci-Fi Comedy is a Strangely Manipulative, Self-Aware Allegory

Is Mark Ruffalo doing a Trump impression? It happens early in Bong Joon Ho’s Mickey 17 when the actor appears in a luxurious blazer, accompanied by his wife Ylfa (Toni Collette), reveling in the applause of a crowd that stands and cheers as if he were a messianic figure. Ruffalo plays Kenneth Marshall, the head of a cult-like Church.