Director Adam Elliot's Memoir of a Snail: Crafting an Emotional Journey for His Audience and His Reason for Not Winning an Oscar

Two decades ago, stop-motion animator Adam Elliot made a remarkable entrance in the film world with his charming short film, Harvie Krumpet. Centered around a man plagued by persistent bad luck, it earned him an Oscar, showcasing Elliot’s unique sense of humor, big heart, and distinctive animation style. A blend of ugliness and beauty, Elliot’s stop-motion creations stood apart from the works of Henry Selick and Nick Park. His clay figures—imperfect yet lovingly detailed—experience lives filled with both comedy and tragedy. His artistry often delves into existential themes, reflecting his personal life experiences.

Elliot refers to his craft as "Clayography," viewing it as animation aimed at adults. His films address themes of death, disease, and calamity, covering various aspects of human experience. While he doesn’t shy away from depicting harsh realities like obesity, addiction, or mortality, he imbues a warmth and humor in these disasters that allows audiences of all ages to connect. The handmade, textured quality of his work—crafted solely from raw materials—helps distinguish him from other animators. Unlike Pixar, which tends to simplify profound topics for its younger audience, Elliot’s storytelling challenges viewers to confront these themes directly.

Now, twenty years after winning his first Oscar, Elliot returns to the awards scene with his outstanding feature, Memoir of a Snail. This film continues to explore significant themes like death, addiction, and otherness, focusing on the life of an aspiring stop-motion animator named Grace Pudel (Sarah Snook). The story begins as Grace reflects on the life of her dearest friend, Pinky, an eccentric elderly woman, while she releases her beloved snail, Sylvia, in Pinky’s backyard. Grace’s childhood was spent in poverty with her widowed, alcoholic father, a former street performer in Paris, until his untimely death led to a string of misfortunes after being separated from her brother Gilbert and placed in different foster homes. With only her pet snails for companionship, she finds solace in overeating and hoarding, a spiral depicted through Elliot’s compassionate lens.

Despite the somber themes, Elliot's signature quirky humor lightens the weight of these inherently human struggles. His “blobby” clay characters are some of the most relatable figures seen on screen.

Before the Oscars, I had the opportunity to sit down with Adam Elliot for a thorough discussion on the empathetic portrayal of disability and disfigurement, tackling mental illness, thriving in what some consider a “dead medium,” and more.

The Film Stage: I love how your work often circles back to this Kierkegaard quote: “Life can only be understood backwards, but you must live it forwards.” You featured this in your short Uncle long ago and referenced it again in Memoir of a Snail. Was there a moment when you realized, “Ah, this quote really resonates with the life of a snail”?

Adam Elliot: That is indeed one of my favorite quotes, and yes, I’ve reused it simply because I cherish it. I stumbled upon it during my mid-20s, and it struck me profoundly. It's somewhat simplistic, yet there’s depth in its simplicity, and I strive to apply it to my own life. I tend to be a worrier—I've got a bit of OCD and often find myself obsessing over what has happened in the past, wasting a lot of time and energy. So I keep reminding myself: let go of yesterday and focus on today and tomorrow. This film felt like the right place to include quotes I admire, and this one kept resonating with me.

It has significant importance for Grace as she breaks free from her addictions and processes trauma and loss. She needs to purge and move forward to become whole again. I must admit I wish I could claim it as my own, but it belongs to Søren Kierkegaard. I may have first come across it in high school, and it truly resonated with me in my mid-20s. I did worry that it might be too simplistic for this film, especially as I grow older and more philosophical. But it turns out younger audiences are quoting it on Letterboxd and social media, while older folks may have heard it many times before. [Laughs]

Your work often addresses themes of disability, disfigurement, and illness. In Harvie Krumpet, the protagonist copes with Tourette's and addiction, while Grace here navigates life with a cleft palate and struggles with obesity and hoarding. Animation has traditionally depicted these subjects mockingly, but your work conveys a strong sense of empathy. What does it mean to you to provide representation for those living with these conditions?

Absolutely. That’s a great question. It’s incredibly important because these characters reflect my family and friends, and I'm respectful towards them. I put sincerity into the writing, aiming for accurate representations. For instance, my last film, Mary and Max, was

Other articles

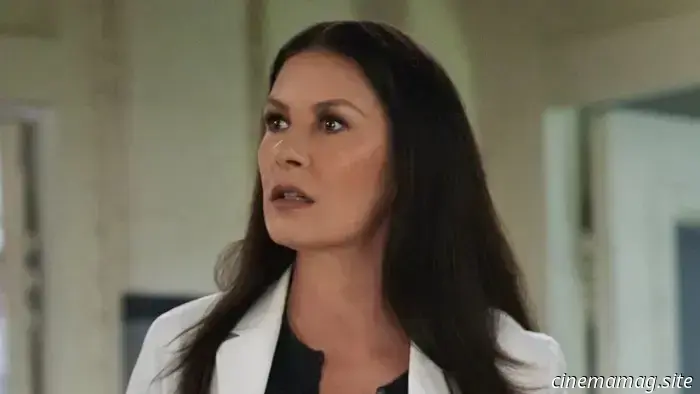

Catherine Zeta-Jones will lead the cast in the thriller series Kill Jackie.

The talented Oscar, BAFTA, and Tony Award-winning Catherine Zeta-Jones is set to take the lead in a new series based on Aidan Truhen's "gonzo thriller," The Price You Pay, which is currently working under the title Kill Jackie. According to Deadline, “the series is being produced for Prime Video, Fremantle, and Steel Springs Pictures. Amazon holds the rights in multiple [...]

Catherine Zeta-Jones will lead the cast in the thriller series Kill Jackie.

The talented Oscar, BAFTA, and Tony Award-winning Catherine Zeta-Jones is set to take the lead in a new series based on Aidan Truhen's "gonzo thriller," The Price You Pay, which is currently working under the title Kill Jackie. According to Deadline, “the series is being produced for Prime Video, Fremantle, and Steel Springs Pictures. Amazon holds the rights in multiple [...]

Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe will feature in The Weight.

The Hollywood Reporter has announced a formidable collaboration between Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe. According to the publication, Hawke and Crowe will feature in The Weight, a forthcoming historical epic taking place in Oregon in 1933. Padraic McKinley is set to direct, utilizing an original screenplay written by Shelby Gaines, Matthew Chapman, and Matthew Booi, which is based on an original story [...]

Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe will feature in The Weight.

The Hollywood Reporter has announced a formidable collaboration between Ethan Hawke and Russell Crowe. According to the publication, Hawke and Crowe will feature in The Weight, a forthcoming historical epic taking place in Oregon in 1933. Padraic McKinley is set to direct, utilizing an original screenplay written by Shelby Gaines, Matthew Chapman, and Matthew Booi, which is based on an original story [...]

David Lynch: The Significant Mystery of American Cinema

Simon Thompson delves into the legacy of the late, remarkable David Lynch. To begin this piece in the most straightforward manner, David Lynch, one of the most unique directors in American cinema, has passed away. Although I was aware that his health had sadly deteriorated since 2020, it still seems nearly unimaginable to come to terms with […]

David Lynch: The Significant Mystery of American Cinema

Simon Thompson delves into the legacy of the late, remarkable David Lynch. To begin this piece in the most straightforward manner, David Lynch, one of the most unique directors in American cinema, has passed away. Although I was aware that his health had sadly deteriorated since 2020, it still seems nearly unimaginable to come to terms with […]

The Breakfast Club at 40: The Tale Behind the Defining Coming-of-Age Teen Drama of the 1980s

As the film celebrates its 40th anniversary, Hasitha Fernando explores the background of John Hughes' iconic 80s film, The Breakfast Club. John Hughes is a name that epitomizes coming-of-age teen dramas from the 1980s, but one film consistently shines as one of his finest works: The Breakfast Club. [...]

The Breakfast Club at 40: The Tale Behind the Defining Coming-of-Age Teen Drama of the 1980s

As the film celebrates its 40th anniversary, Hasitha Fernando explores the background of John Hughes' iconic 80s film, The Breakfast Club. John Hughes is a name that epitomizes coming-of-age teen dramas from the 1980s, but one film consistently shines as one of his finest works: The Breakfast Club. [...]

-Movie-Review.jpg) Into the Deep (2025) - Film Review

Into the Deep, 2025. Directed by Christian Sesma. Featuring Scout Taylor-Compton, Richard Dreyfuss, Stuart Townsend, Jon Seda, AnnaMaria Demara, Tom O’Connell, Callum McGowan, Lorena Sarria, Ron Smoorenburg, Tofan Pirani, Quinn P Hensley, and Maverick Kang Jr. SYNOPSIS: Present-day pirates seek out sunken drugs and abduct a group of tourists on a boat, compelling them to […]

Into the Deep (2025) - Film Review

Into the Deep, 2025. Directed by Christian Sesma. Featuring Scout Taylor-Compton, Richard Dreyfuss, Stuart Townsend, Jon Seda, AnnaMaria Demara, Tom O’Connell, Callum McGowan, Lorena Sarria, Ron Smoorenburg, Tofan Pirani, Quinn P Hensley, and Maverick Kang Jr. SYNOPSIS: Present-day pirates seek out sunken drugs and abduct a group of tourists on a boat, compelling them to […]

-Blu-ray-Review.jpg) Review of the Blu-ray Release of Legend of the Eight Samurai (1983)

Legend of the Eight Samurai, released in 1983, was directed by Kinji Fukasaku and features performances by Hiroko Yakushimaru, Sonny Chiba, Hiroyuki Sanada, Yuki Meguro, Masaki Kyômoto, Kenji Ôba, and Mari Natsuki. SYNOPSIS: A princess is pursued by a rival clan that has been annihilated and subsequently resurrected as demons. This film is inspired by the expansive 19th-century novel Nanso Satomi […]

Review of the Blu-ray Release of Legend of the Eight Samurai (1983)

Legend of the Eight Samurai, released in 1983, was directed by Kinji Fukasaku and features performances by Hiroko Yakushimaru, Sonny Chiba, Hiroyuki Sanada, Yuki Meguro, Masaki Kyômoto, Kenji Ôba, and Mari Natsuki. SYNOPSIS: A princess is pursued by a rival clan that has been annihilated and subsequently resurrected as demons. This film is inspired by the expansive 19th-century novel Nanso Satomi […]

Director Adam Elliot's Memoir of a Snail: Crafting an Emotional Journey for His Audience and His Reason for Not Winning an Oscar

Twenty years ago, stop-motion animator Adam Elliot made his debut with the charming short film Harvie Krumpet. Centering on a man plagued by perpetual misfortune, it won him an Oscar and showcased Elliot's unique sense of humor, immense compassion, and distinctive animation style. A blend of the imperfect and the beautiful, entirely