Berlinale Review: Reflection in a Dead Diamond Delivers a Frenzied, Intense Assault on the Senses

Whether positive or negative, all critical evaluations of Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani’s films inevitably converge on a central theme: their overwhelming love for cinema. This is justified, given that the Belgian duo's body of work––encompassing four feature films and several shorts––is rich with references to a seemingly infinite stream of Italian giallos from directors like Mario Bava, Sergio Martino, and Dario Argento. This could be described as an act of “cinematic rehabilitation,” as Justin Chang noted in his review of Let the Corpses Tan––though that might only be true if one believes that particular mix of hyper-stylized pulp requires rehabilitation in the first place. Thus arises the somewhat simplistic notion: enthusiasts of the classic films Cattet and Forzani reference will undoubtedly enjoy their work, while others may dismiss it as empty homage––or, as Stephen Holden rather harshly characterized their 2009 film Amer, “recycled psychosexual kitsch.”

If the either-or discussion feels particularly stifling, it’s because it assumes that only aficionados of giallo will appreciate the pleasures Cattet and Forzani create. However, those delights are not merely academic. Instead of being mere echoes of vintage titles, their films possess an alluring power that is distinctly their own––along with a carefree disregard for plot conventions, making the viewing experience akin to being trapped in a whirlpool where normal rules of physics and storytelling do not apply.

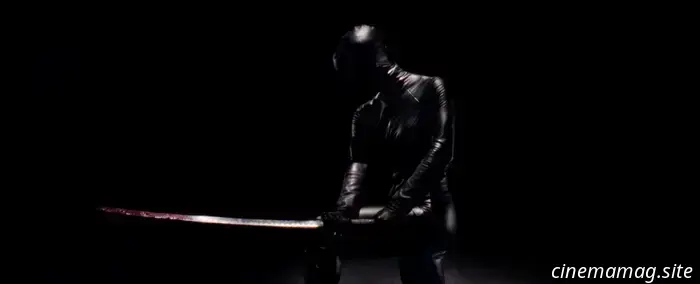

Introducing Reflection in a Dead Diamond. Set in an unspecified area of southern France, the same Mediterranean locale featured in Amer and Corpses, Diamond follows a seventy-something retired spy, Monsieur Diman (Fabio Testi), whose stay at a lavish seaside hotel is abruptly interrupted by fears that his former adversaries may be pursuing him once more. This is a decidedly succinct summary of what is, in reality, an intricately woven narrative, a Russian Doll-like structure of stories nested within stories within films. Diman’s younger, James Bond-like self (Yannick Renier), whose grisly missions continuously intersect with the old man’s retreat through a series of flashbacks, is not an actual spy, but rather a character from a B-movie espionage saga, one “John D.” In essence, the increasingly violent memories Diman is unearthing between martinis may have more to do with fantasies surrounding his own fictional persona than with any real-life experiences.

Nonetheless, Diamond shows such little regard for logic that discerning the line between reality and hallucination would be missing the point. Those familiar with Cattet and Forzani’s work will recognize the type of thrills their films consistently provide. For newcomers, the experience may come across––and I say this as the highest compliment––as an assault on the senses. Like its forerunners, Diamond unfolds as a kind of feverish mirage. It’s a film where the camera rarely remains stationary, shots typically last no longer than five seconds, and the frame constantly fractures with the same ecstatic joy that characters exhibit whenever they stab or slice through flesh (which occurs frequently). Manuel Dacosse, who has filmed all of the couple’s previous works, employs a color palette saturated in vivid crimsons and blues, shifting between extreme close-ups of eyes and mouths reminiscent of Spaghetti Westerns and Argento-style depictions of knives and stilettos piercing skin. This film is one where the camera needs only to tilt up to the sky and back down to the earth for the narrative to transition from the present to the past, moving from one fiction to another. It features images drawn from nightmares––like a massive millipede crawling over a corpse––and others that are striking in their creativity, such as an evening gown worn by one of John D's female companions made entirely of sequins the size of two-euro coins that dart in all directions like dazzling daggers, harming everyone in their path.

Another aspect often overlooked in critical discussions about Cattet and Forzani is the playful nature of their films. Despite, or perhaps because of, all the bloodshed and narrative twists, Diamond is an exceptionally humorous viewing experience. This makes me reluctant to label it as an homage. On one level, that’s technically accurate, but the type of tributes Diamond presents are not filled with reverence. One can sense the directors having fun as they provoke and dissect foundational texts, ranging from giallos to influential Italian comic books like Diabolik. Their exuberance is infectious. The appearance of Maria de Medeiros, who steps into Diamond as Diman's former lover, brings to mind a filmmaker she once collaborated with, Quentin Tarantino, another director known for his homages. However, while Tarantino’s films often reference other esteemed directors with a self-congratulatory tone (similar to an instantly meme-worthy moment from Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood), Cattet and Forzani manage to transform their cinephilia into something

Other articles

10 Unapologetic New Comedies That Don't Mind If You Are Offended

These bold new comedies are unbothered by whether you're offended — and challenge the notion that modern films shy away from humor. Comedy is very much alive, as these

10 Unapologetic New Comedies That Don't Mind If You Are Offended

These bold new comedies are unbothered by whether you're offended — and challenge the notion that modern films shy away from humor. Comedy is very much alive, as these

The trailer for Freaky Tales showcases Pedro Pascal and Ben Mendelsohn in an expansive story set in the '80s.

Lionsgate has unveiled the trailer for Freaky Tales, the latest film by Captain Marvel writers and directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck. This film is ambitiously described as four interlinked narratives set in Oakland, CA in 1987, exploring themes of music, cinema, relationships, locations, and memories that extend beyond our comprehendible universe. Freaky Tales features Pedro Pascal (The Fantastic Four: [...]

The trailer for Freaky Tales showcases Pedro Pascal and Ben Mendelsohn in an expansive story set in the '80s.

Lionsgate has unveiled the trailer for Freaky Tales, the latest film by Captain Marvel writers and directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck. This film is ambitiously described as four interlinked narratives set in Oakland, CA in 1987, exploring themes of music, cinema, relationships, locations, and memories that extend beyond our comprehendible universe. Freaky Tales features Pedro Pascal (The Fantastic Four: [...]

-Movie-Review.jpg) Cleaner (2025) - Film Review

Cleaner, 2025. Directed by Martin Campbell. Featuring Daisy Ridley, Clive Owen, Taz Skylar, Flavia Watson, Ray Fearon, Rufus Jones, Richard Hope, Lee Boardman, Stella Stocker, Atanas Srebrev, Celine Arden, Akie Kotabe, Poppy Townsend White, Andreea Diac, Rachel Kwok, Lorna Lowe, Cassandra Spiteri, Frances Katz, Mélissa Humler, Ben Essex, and Karin Carlson. SYNOPSIS: Criminal activists take control of […]

Cleaner (2025) - Film Review

Cleaner, 2025. Directed by Martin Campbell. Featuring Daisy Ridley, Clive Owen, Taz Skylar, Flavia Watson, Ray Fearon, Rufus Jones, Richard Hope, Lee Boardman, Stella Stocker, Atanas Srebrev, Celine Arden, Akie Kotabe, Poppy Townsend White, Andreea Diac, Rachel Kwok, Lorna Lowe, Cassandra Spiteri, Frances Katz, Mélissa Humler, Ben Essex, and Karin Carlson. SYNOPSIS: Criminal activists take control of […]

Trailer for "Eric LaRue," directed by Michael Shannon and featuring Judy Greer.

Magnolia Pictures has unveiled a poster and trailer for Eric LaRue, marking the directorial debut of Michael Shannon. The film, which is based on Brett Neveu’s 2002 play of the same name, features Judy Greer in the role of Janice, a mother attempting to find comfort in her faith as she navigates the consequences following her son's […].

Trailer for "Eric LaRue," directed by Michael Shannon and featuring Judy Greer.

Magnolia Pictures has unveiled a poster and trailer for Eric LaRue, marking the directorial debut of Michael Shannon. The film, which is based on Brett Neveu’s 2002 play of the same name, features Judy Greer in the role of Janice, a mother attempting to find comfort in her faith as she navigates the consequences following her son's […].

The Actor Trailer: Noir Drama Starring André Holland Debuts This March

Following co-directing Anomalisa with Charlie Kaufman, there has been significant anticipation for Duke Johnson's upcoming feature The Actor. It has been ten years since the director's last film, and now the drama is slated for release by NEON, arriving sooner than anticipated. The noir, featuring André Holland, is set to hit theaters in less than a month, on March 14.

The Actor Trailer: Noir Drama Starring André Holland Debuts This March

Following co-directing Anomalisa with Charlie Kaufman, there has been significant anticipation for Duke Johnson's upcoming feature The Actor. It has been ten years since the director's last film, and now the drama is slated for release by NEON, arriving sooner than anticipated. The noir, featuring André Holland, is set to hit theaters in less than a month, on March 14.

SNL at 50: The 12 Most Astonishing Moments in Saturday Night Live's History

SNL, or Saturday Night Live, has presented numerous astonishing moments in live television. Here are 12 of those instances.

SNL at 50: The 12 Most Astonishing Moments in Saturday Night Live's History

SNL, or Saturday Night Live, has presented numerous astonishing moments in live television. Here are 12 of those instances.

Berlinale Review: Reflection in a Dead Diamond Delivers a Frenzied, Intense Assault on the Senses

Whether positive or negative, every critical assessment of Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani’s films ultimately converges on a common theme: their overwhelming passion for cinema. This observation is justified, as the Belgian duo's body of work—which now includes four feature films and several shorts— is filled with references to a seemingly infinite array of Italian giallos, including those by Mario Bava.