Harvest Review: Athina Rachel Tsangari Elegantly Depicts the Past in the Present

Note: This review was initially published as part of our coverage of the 2024 Venice Film Festival. Harvest is set to hit theaters on August 1 and will be available on MUBI starting August 8.

Set in an unnamed village during an unspecified time in the Late Middle Ages in Britain, Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Harvest captures the end of an old social order, yet it refrains from lamenting a lost paradise. Such a comparison would be overly simplistic for a filmmaker known for intertwining allegorical themes with political issues, like gender dynamics in Attenberg and Chevalier. Nine years after her last film, the Greek director returns to feature filmmaking with an adaptation of Jim Crace’s celebrated novel, marking Harvest as her third film and her first period piece.

The harvest season is characterized by warm yellows (in the fields), vibrant greens (in the meadows), and deep blues (of the lake). Within this beauty exists Walter Thirsk (Caleb Landry Jones), a villager whose bright eyes and pale complexion may mislead observers: he is profoundly connected to this natural world––its cycles, foliage, and grasses––with the camera capturing him as an extension of his environment. Sean Price Williams has cinematographed Harvest enchantingly, applying his characteristic dynamism—typically focused on human expressions and actions—to landscapes and village rituals with a unique tenderness found in pans, zooms, and close-ups.

As the film unfolds, we learn that Walter is not a native of this land. He and the mayor, Charles Kent (a notably vulnerable Harry Melling), were childhood friends in a different town. After Kent married his late wife, he acquired the land and farms, while Walter fell in love with a local woman and left his position as manservant. This context is crucial for grounding the characters, who convey depth without excessive detail. Strong connections unite the village, overshadowed by occasional gossip and suspicion, which is evident in their interactions. The communal relationships stand out, not only due to Master Kent’s generosity but also because of his palpable sorrow, suggesting that his deceased wife continues to influence the villagers.

However, the seeds of change and progress have already been planted, disturbing the pastoral peace. A group of outsiders is caught, humiliated, and imprisoned as scapegoats for a recent fire, while the commons are facing privatization. Although Harvest does not directly address the Enclosure Act of 1604, which affected open fields and common land in England and Wales, it illustrates the broader shift from agricultural practices to industrialization. Given Tsangari’s previous work and its political themes, it is unsurprising to witness a world symbolically deteriorating in just a week, devoid of nostalgia. Sentimentality does not interest the Greek director; instead, her films maintain a sensitive and caring approach, especially towards their flawed characters.

With a screenplay co-written by Tsangari and Oscar nominee Joslyn Barnes, Harvest adheres closely to its source material, though it prominently features Walter as the main character. His sparse yet guiding voiceover, combined with Landry Jones' expressive eyes, places him at the forefront, while his silent observations resonate powerfully. The complex emotions at the heart of this film (a non-nostalgic acknowledgment of loss) are most vividly expressed in interactions between Walter and a cartographer portrayed by Arinzé Kene. The mere presence of maps hints at emerging concepts of property, profitability, and colonialism, alongside maps that portray landscapes as if they were dynamic, living entities. Upon encountering such a map, Walter––clearly captivated by the village and its environment––addresses it as if it were magic.

Just as a mapped portion of land can influence a person, Harvest champions the transformative power of cinema to reawaken wonder in the world. Numerous scenes evoke comparisons to Terrence Malick’s grand humanism (both in tone and visuals), yet Tsangari transcends those comparisons. Transitions are seldom easy to encapsulate, often only making sense in hindsight; nonetheless, Harvest (both the film and the book) operates on a humanistic and micro-historical level, conjuring the sensation that one could momentarily inhabit a bygone past––as if it were a myth––before facing the harsh reality that ultimately encroaches upon our present and future.

Harvest had its premiere at the 2024 Venice Film Festival.

Other articles

The G.O.A.T. is an actual goat in the trailer for the animated film Goat, produced by Stephen Curry.

Sony Pictures Animation has unveiled the trailer for their animated feature film Goat, produced by Stephen Curry. Directed by Tyree Dillihay (Bob’s Burgers) and Adam Rosette (The Wild Robot), Goat boasts a stellar cast of voice actors, which includes Caleb McLaughlin, Gabrielle Union, Stephen Curry, Nicola Coughlan, Nick Kroll, David Harbour, Jenifer Lewis, Aaron Pierre, Patton and others.

The G.O.A.T. is an actual goat in the trailer for the animated film Goat, produced by Stephen Curry.

Sony Pictures Animation has unveiled the trailer for their animated feature film Goat, produced by Stephen Curry. Directed by Tyree Dillihay (Bob’s Burgers) and Adam Rosette (The Wild Robot), Goat boasts a stellar cast of voice actors, which includes Caleb McLaughlin, Gabrielle Union, Stephen Curry, Nicola Coughlan, Nick Kroll, David Harbour, Jenifer Lewis, Aaron Pierre, Patton and others.

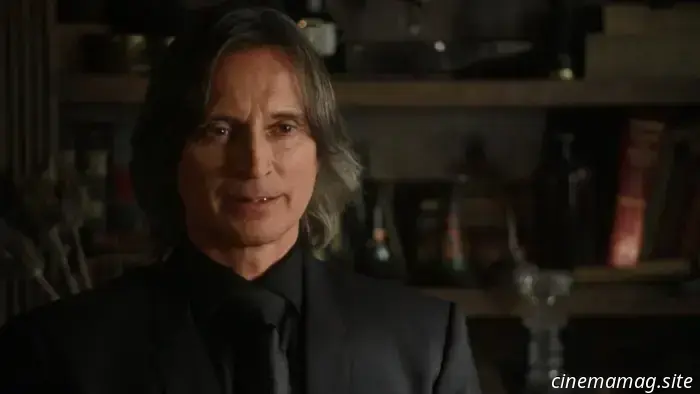

Robert Carlyle will take on the role of Sherlock Holmes in the second season of Watson.

The legendary Sherlock Holmes will be appearing in the CBS medical drama Watson, with Robert Carlyle (Once Upon a Time) joining the cast of the show's second season as the iconic detective when it premieres on October 13th. Watson reinterprets Dr. John Watson in the wake of Sherlock’s crucial confrontation with Professor Moriarty, depicting him as a physician who leads […]

Robert Carlyle will take on the role of Sherlock Holmes in the second season of Watson.

The legendary Sherlock Holmes will be appearing in the CBS medical drama Watson, with Robert Carlyle (Once Upon a Time) joining the cast of the show's second season as the iconic detective when it premieres on October 13th. Watson reinterprets Dr. John Watson in the wake of Sherlock’s crucial confrontation with Professor Moriarty, depicting him as a physician who leads […]

Jack Reynor will be joining Rachel Brosnahan in the second season of Presumed Innocent.

The second season of Apple TV+’s Presumed Innocent has secured its second lead actor. Joining Rachel Brosnahan from Superman is Jack Reynor (The Perfect Couple). Apple has recently transformed Presumed Innocent into an anthology series, with each season featuring a new cast of characters tackling a different murder investigation. The first season was based on Scott [...]

Jack Reynor will be joining Rachel Brosnahan in the second season of Presumed Innocent.

The second season of Apple TV+’s Presumed Innocent has secured its second lead actor. Joining Rachel Brosnahan from Superman is Jack Reynor (The Perfect Couple). Apple has recently transformed Presumed Innocent into an anthology series, with each season featuring a new cast of characters tackling a different murder investigation. The first season was based on Scott [...]

Trailer for Twinless featuring Dylan O'Brien and James Sweeney.

Lionsgate and Roadside Attractions have released a trailer for Twinless, the forthcoming drama by writer-director James Sweeney. The story revolves around two young men, Roman (Dylan O’Brien) and Dennis (Sweeney), who form a bond after they meet at a twin support group. However, they are unaware that both hold secrets that could jeopardize their relationship. Alongside O’Brien and […]

Trailer for Twinless featuring Dylan O'Brien and James Sweeney.

Lionsgate and Roadside Attractions have released a trailer for Twinless, the forthcoming drama by writer-director James Sweeney. The story revolves around two young men, Roman (Dylan O’Brien) and Dennis (Sweeney), who form a bond after they meet at a twin support group. However, they are unaware that both hold secrets that could jeopardize their relationship. Alongside O’Brien and […]

Twinless Trailer: Dylan O’Brien and James Sweeney Develop an Enigmatic Connection in Sundance Winner

One of the most talked-about films debuting at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival, where it took home the Audience Award, James Sweeney's Twinless will be released on September 5 by Roadside Attractions. Featuring Sweeney alongside Dylan O’Brien, Lauren Graham, Aisling Franciosi, Tasha Smith, and Chris Perfetti, the initial trailer has now been unveiled.

Twinless Trailer: Dylan O’Brien and James Sweeney Develop an Enigmatic Connection in Sundance Winner

One of the most talked-about films debuting at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival, where it took home the Audience Award, James Sweeney's Twinless will be released on September 5 by Roadside Attractions. Featuring Sweeney alongside Dylan O’Brien, Lauren Graham, Aisling Franciosi, Tasha Smith, and Chris Perfetti, the initial trailer has now been unveiled.

Te Ao o Hinepehinga discusses their experience acting in Chief of War alongside Jason Momoa - Exclusive Interview.

Tai Freligh speaks with Te Ao o Hinepehinga, star of Chief of War. The Polynesian (Māori) actress Te Ao o Hinepehinga plays an important role in the much-awaited Apple TV+ drama series Chief of War, set to debut on August 1, 2025. She will appear alongside Jason Momoa, portraying his character’s wife, ‘Kupuohi’. Filmed in Hawaii, the cast [...]

Te Ao o Hinepehinga discusses their experience acting in Chief of War alongside Jason Momoa - Exclusive Interview.

Tai Freligh speaks with Te Ao o Hinepehinga, star of Chief of War. The Polynesian (Māori) actress Te Ao o Hinepehinga plays an important role in the much-awaited Apple TV+ drama series Chief of War, set to debut on August 1, 2025. She will appear alongside Jason Momoa, portraying his character’s wife, ‘Kupuohi’. Filmed in Hawaii, the cast [...]

Harvest Review: Athina Rachel Tsangari Elegantly Depicts the Past in the Present

Note: This review was initially published as part of our coverage for Venice 2024. Harvest will premiere in theaters on August 1 and will be available on MUBI starting August 8. In an unnamed village and an unspecified time; in Britain during the Late Middle Ages, something is on the verge of concluding. Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Harvest portrays the dusk of