You Burn Me Review: Matías Piñeiro Reflects on Sapphic Fragments and Unreciprocated Affection

In You Burn Me, the Argentinian writer and filmmaker Matías Piñeiro employs his vintage Bolex camera much like the iOS Notes app. Over several years, his approach involved "collecting" images during various teaching roles across two continents, capturing real locations mentioned in the texts he’s adapting, as well as places mimicking them. While his work has consistently engaged with the relevance of classical literary texts today, this latest effort more urgently reflects on film form, particularly exploring how the avant-garde canon of the '60s, shot on 16mm and created by cooperatives, can be updated. Similar to Sappho’s Ancient Greek poetry—his other primary focus—his rushes resemble countless, shining fragments, with a sprawling database serving as a substitute for the poet's parchment.

This creates a productive tension as Piñeiro strives to transform literary sources into cinema: it is never merely a physical enactment or maintained through voice-over; instead, the emphasis remains on employing native cinematic language (images, découpage) to replicate the sensual and semantic qualities of language. By examining Sappho’s evocative language (likely composed in the fifth century BC and translated here by Anne Carson), the three syllables that make up "you burn me" clearly provoke Piñeiro to consider a cinematic counterpart for their succinct beauty.

While Piñeiro's Shakespeare adaptations from the 2010s (such as Viola and Hermia & Helena) were rich and allusive, he achieves a greater structural depth in You Burn Me by using the mythological works of Italian anti-fascist writer Cesare Pavese as a framework to explore Sappho’s more minimalist writings. Anglophone film enthusiasts might recognize Pavese as a significant influence on Straub-Huillet, and in their spirit, Piñeiro seeks to establish a rigorous cinematic language for his 1947 text Dialogues With Leucò, particularly the chapter “Sea Foam,” which imagines an interaction between Sappho and the mountain nymph Britomartis, both of whom are apocryphally said to have drowned themselves. When Pavese also took his own life in 1950 in a hotel in his native Turin, he left his last words written in a copy of this very book.

With the director's frequent collaborator Agustina Muñoz portraying an unseen filmmaker reflecting in voice-over on a potential adaptation of “Sea Foam,” the components of the story gradually come together alongside her commentary. Piñeiro regulars Gabriela Saidón and María Villar portray Sappho and Britomartis respectively in modern times, yet in the Mediterranean setting reminiscent of their characters from millennia past; more indirectly, María Inês Gonçalves plays a biology student caught in a romantic crisis, as we follow her observing classical artifacts in a museum, further illustrating Sappho’s world. Editor Gerard Borràs’ rapid cutting and interwoven density mimic the associations we experience while reading, as well as the more complex scholarly engagement if we decide to study these texts, necessitating translations between Spanish, Italian, the Aeolian dialect of Ancient Greek, and English for full comprehension to emerge.

Some of Piñeiro’s dialectical connections may be clearer to him than to us, and while he possesses the self-driven independence and literary insight akin to his major influence Hong Sangsoo, the South Korean director’s DIY works tend to resonate more universally, making it easier to access their emotional wavelength. Nonetheless, You Burn Me establishes Piñeiro as one of the most visionary figures in contemporary experimental film, inviting us to follow along even if he is several intellectual steps ahead.

You Burn Me is currently in limited release.

Other articles

Neil Patrick Harris is set to join the cast of Dexter: Resurrection.

As filming for Dexter: Resurrection progresses, Showtime has revealed that Neil Patrick Harris from How I Met Your Mother is the newest addition to the cast of the upcoming season of Dexter. Dexter: Resurrection will begin where New Blood left off, with Dexter being shot by his son Harrison as he attempts to evade the authorities and seek redemption for his past actions. However, […]

Neil Patrick Harris is set to join the cast of Dexter: Resurrection.

As filming for Dexter: Resurrection progresses, Showtime has revealed that Neil Patrick Harris from How I Met Your Mother is the newest addition to the cast of the upcoming season of Dexter. Dexter: Resurrection will begin where New Blood left off, with Dexter being shot by his son Harrison as he attempts to evade the authorities and seek redemption for his past actions. However, […]

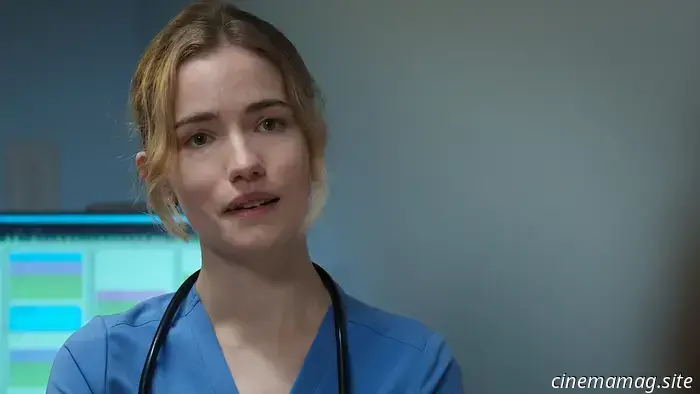

Netflix unveils trailer for medical drama Pulse featuring Willa Fitzgerald.

Today, Netflix has unveiled the new trailer for Pulse, the streaming service's inaugural medical drama featuring Willa Fitzgerald (Reacher) as Danny Sims, a young physician who is appointed chief resident during a hurricane lockdown that leads to various complications. Pulse also features Willa Fitzgerald (Reacher), Justina Machado (One Day at a Time), Colin Woodell (The Continental), Jack Bannon (Pennyworth), […]

Netflix unveils trailer for medical drama Pulse featuring Willa Fitzgerald.

Today, Netflix has unveiled the new trailer for Pulse, the streaming service's inaugural medical drama featuring Willa Fitzgerald (Reacher) as Danny Sims, a young physician who is appointed chief resident during a hurricane lockdown that leads to various complications. Pulse also features Willa Fitzgerald (Reacher), Justina Machado (One Day at a Time), Colin Woodell (The Continental), Jack Bannon (Pennyworth), […]

Arian Moayed and Alex Karpovsky are set to take part in season 2 of Nobody Wants This.

Following the recent casting of Leighton Meester and Miles Fowler in the popular Netflix romantic comedy series Nobody Wants This, Deadline has announced that Arian Moayed (Succession) and Alex Karpovsky (Girls) will be joining the show for its second season. Nobody Wants This centers on Kristen Bell and Adam Brody's characters, Joanne and Noah, a couple of adults who embark on an […]

Arian Moayed and Alex Karpovsky are set to take part in season 2 of Nobody Wants This.

Following the recent casting of Leighton Meester and Miles Fowler in the popular Netflix romantic comedy series Nobody Wants This, Deadline has announced that Arian Moayed (Succession) and Alex Karpovsky (Girls) will be joining the show for its second season. Nobody Wants This centers on Kristen Bell and Adam Brody's characters, Joanne and Noah, a couple of adults who embark on an […]

The 15 Most Hilarious TV Shows We've Ever Watched

Here are the most hilarious TV shows we've ever watched. Let's dive in.

The 15 Most Hilarious TV Shows We've Ever Watched

Here are the most hilarious TV shows we've ever watched. Let's dive in.

Hasbro broadens its Retro Collection by introducing a new multipack inspired by Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope.

Hasbro is broadening its Star Wars: Retro Collection action figures by introducing a new multipack featuring six figures from Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. This set includes a reproduction of the original Kenner Walrus Man (also known as Ponda Baba) alongside new figures that have not previously been released, including Dr. Evazan and Han Solo in an Imperial Stormtrooper Outfit, among others.

Hasbro broadens its Retro Collection by introducing a new multipack inspired by Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope.

Hasbro is broadening its Star Wars: Retro Collection action figures by introducing a new multipack featuring six figures from Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. This set includes a reproduction of the original Kenner Walrus Man (also known as Ponda Baba) alongside new figures that have not previously been released, including Dr. Evazan and Han Solo in an Imperial Stormtrooper Outfit, among others.

A Palestinian educator stands her ground in the U.S. trailer for Farah Nabulsi’s highly praised film, The Teacher.

After No Other Land's significant Oscar victory earlier this week, more films highlighting the struggles of the Palestinian people are receiving broader distribution in the United States. This spring, the drama The Teacher, directed by Oscar-nominated Farah Nabulsi and featuring Saleh Bakri and Imogen Poots, will be released by Watermelon Pictures following its selection at TIFF. An April release is anticipated.

A Palestinian educator stands her ground in the U.S. trailer for Farah Nabulsi’s highly praised film, The Teacher.

After No Other Land's significant Oscar victory earlier this week, more films highlighting the struggles of the Palestinian people are receiving broader distribution in the United States. This spring, the drama The Teacher, directed by Oscar-nominated Farah Nabulsi and featuring Saleh Bakri and Imogen Poots, will be released by Watermelon Pictures following its selection at TIFF. An April release is anticipated.

You Burn Me Review: Matías Piñeiro Reflects on Sapphic Fragments and Unreciprocated Affection

In You Burn Me, Argentinian writer-director Matías Piñeiro utilizes his vintage Bolex camera similarly to the iOS Notes app. Over a span of several years, his approach entailed “collecting” images from various locations while juggling teaching positions across two continents, in actual sites mentioned in the texts he is adapting, along with other places.